In 1964, at the apogee of Beatlemania, The Fab Four and film director Richard Lester released A Hard Day’s Night, which made $11 million and dispelled any lingering doubts about the cultural importance of the long-haired lads from Liverpool. The film proved to be one of mainstream cinema’s most seminal musicals—formally, aesthetically, and commercially—and its influence has seeped into the foundations of popular culture, especially with the advent of music videos and MTV in the 1980s, and in the more recent trend of feature-length visual albums.

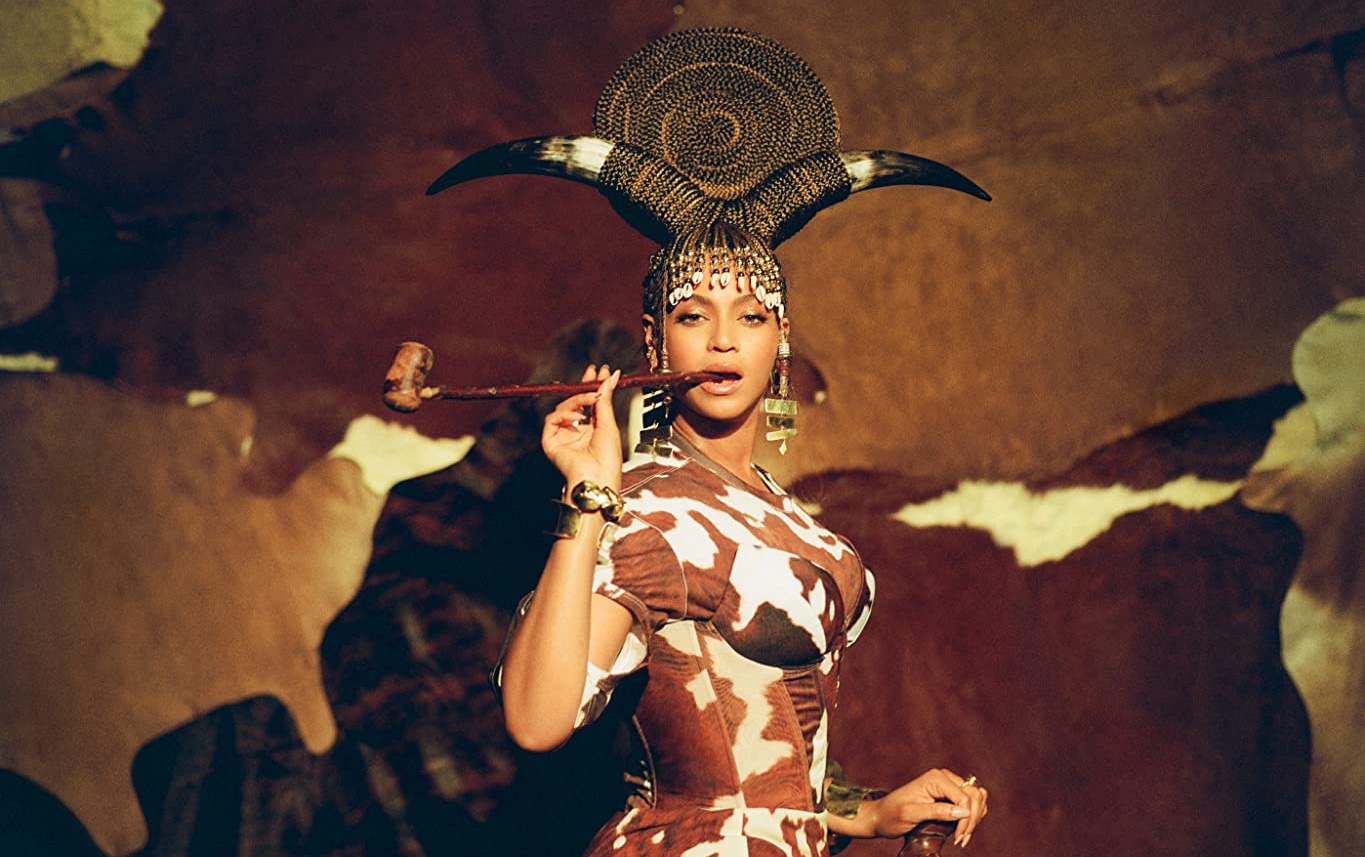

Beyoncé‘s Black Is King, an eighty-five-minute visual companion to The Lion King: The Gift (the tie-in soundtrack for Jon Favreau’s 2019 The Lion King that Beyoncé curated), belongs to the lineage established by Lester’s film (i.e., it is inextricably bound to an already-existing work, a corporate creation that uses a popular artist to advertise a product), but its style—the visual mood and filmmaking techniques and slick, expensive presentation—is of the moment.

Beyoncé sparked the current fervor for visual albums with a film based on her 2013 self-titled album, and three years later, she released Lemonade, one of the era’s defining achievements. According to Billboard, the album would later sell eighty thousand copies on iTunes in just three hours. (Her husband, Jay-Z, took a similar approach earlier that decade with Watch the Throne, his collaboration with Kanye West, which, after leaking unexpectedly online, was given a sudden digital release one week before hitting brick-and-mortar stores.)

Lemonade, directed by Beyoncé and her cadre of chosen filmmakers (including Jonas Åkerlund, who helmed Madonna’s “Ray of Light,” and Mark Romanek, one of ’90s MTV’s most reliable presences), is a medley of different aesthetics and visual styles held together by Beyoncé’s indelible presence. The hour-long work is shot and edited with an uncommon dexterity and intent, an uncorrupted vision alive with anger and love. While Lemonade suffered from the occasional disjointedness that comes with using multiple filmmakers, it proved seminal, pervading popular culture with its tweet-ready lines (“Boy, bye”) and triumphant scene of the disrespected woman bashing cars with a baseball bat to let out her frustration with her philandering husband. Lemonade felt personal and passionate, an uncompromised vision from one of the most indispensable voices of this generation.

The Disneyfication of Beyoncé’s latest visual album Black Is King, however, feels like an avaricious attempt to attract new subscribers to the digital streaming platform. While tangentially related to Favreau’s insufferable “live-action” reboot of The Lion King, Beyoncé’s collection of music when assembled onscreen in Black Is King functions as the inverse of Disney’s 2019 box office beast, which grossed over $1.6 billion worldwide. Favreau’s Lion King was devoid of passion, a CGI disaster that operates like live-action Photoshop.

Beyoncé’s visual interpretation of the soundtrack recontextualizes the pre-established association to last summer’s blockbuster. Black Is King has the same kind of serious, professional look as Lemonade, but it’s cleaner, at times resembling Terrence Malick’s recent essay film Voyage of Time, at others an episode of Planet Earth: high-definition photography of beautiful vistas and shots that rely on established techniques (in composition, lighting, movement), the kind of film that people call “well-made.”

“Black Is King” feels like it was rushed out on an assembly line, fully equipped with all the right pieces, without any instruction on how to assemble them.

Black Is King feels less impassioned, less of a personal vision than Lemonade, or even last year’s Homecoming concert film, which might account for the comparative carelessness in the new movie’s editing. Black Is King feels like it was rushed out on an assembly line, fully equipped with all the right pieces, without any instruction on how to assemble them. It lacks narrative and thematic cohesion, and is structured like a fragmented playlist of music videos haphazardly strung together.

Consider Homecoming, which hit Netflix last April, how the footage of her 2018 Coachella show (glorious, gleeful) is intermeshed with behind-the-scenes footage leading up to the concert, as well as intimate scenes of Beyoncé’s life post-childbirth, scenes that show the ardent, iconic artist being vulnerable, Queen Bey as Mother Bey. There is a purpose to the edits, to the sequences and structure—shots are simpatico, careful, meaningful. It feels honest, free, the work of an artist who has earned the $20 million budget (from her $60 million three-project deal with Netflix). Notice the consideration given to the placement of cameras, to cuts jumping toward and away from the star, wide shots allowing viewers to revel in the glittering spectacle, the synchronized movement of bodies, towers of fire rising and casting a warm glow on the crowd. The filmmaking is imbued with the same sincerity and ambition as the performance.

The precision and fluidity of the editing in Homecoming gives the pacing a captivating sense of momentum. Black Is King has little of the vehemence that distinguishes Beyoncé’s previous work. Shot for shot, the film is formally adequate while lacking the singular vision of its creator. Lemonade compelled audiences with a sense of urgency and import, and it is this aura of importance that eludes Beyoncé in Black Is King. FL