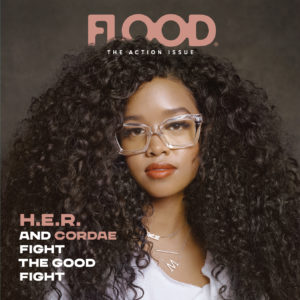

This article appears in FLOOD 11: The Action Issue. You can purchase the magazine here. All proceeds benefit NIVA (National Independent Venue Alliance) and their efforts to save independent venues across the United States. #SaveOurStages

History is swayed by the shifty hands of subjection and perception, a lesson our country continues to grapple with centuries after its foundation as we’re subjected to the lies of the media, the fraudulence of the American Dream, and other deceptive falsehoods that are sold to the U.S. population. History is not the truth. But the truth is something H.E.R., a polymath musician with enough vigor and grace to capture the attention of hundreds in a lecture hall, or thousands in a stadium, is preoccupied with—a personal quest that translates to the music she releases.

In 2016, the first half of her breakout eponymous album revealed H.E.R. to be one of the most captivating R&B voices in recent memory. In the four years since, she’s amassed a pair of Grammy wins, and her catalogue has blossomed into an array of soulful ballads, blues-indebted tribulations, ’90s R&B bangers, and reggae-inspired triumphs. She follows in the footsteps of Marvin Gaye, Lauryn Hill, Fiona Apple, and other musicians that fearlessly deliver prudent lyricism.

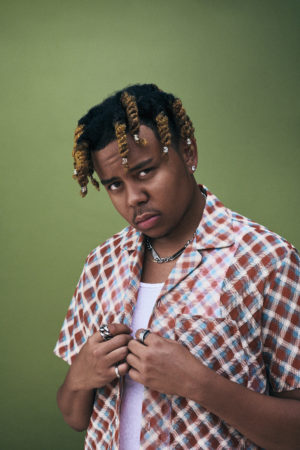

In a time when pseudoscience and political propaganda are virally spreading at the expense of the lives of our country’s Black population, H.E.R.’s music shines like a revelatory light—one that exposes malevolence and generational trauma, while also acting as a galvanizing beacon. Some of her most poignant tracks have been bolstered with verses from fellow musician and activist Cordae, whose lyrics are fueled by the same steadfast faith and unapologetic vulnerability. The two gave an unforgettable performance at the 2019 BET Awards of the ground-shaking “Lord Is Coming” from H.E.R.’s double-EP I Used to Know Her, released that same year.

Donning a shiny black outfit straight out of a Hype Williams video, black sunglasses, and a black beret covered in crystals, H.E.R. took the stage and proceeded to break down several of the monstrosities plaguing our society. “History”—she forcefully pushed the word out of her mouth, as if trying to suck out its venom—“is not my brother’s story. The original founders were buried in the ground where men have planted seeds of disease.” Moments later, Cordae joined her and delivered a remixed rap from “We Gon Make It,” one of the highlights of his debut album The Lost Boy. At the end he shouted, “God Bless America, and God Bless Sudan,” bringing awareness to the human rights crisis in Africa and the global fight for true justice and democracy. A little over a year later, this past July, he would be arrested for protesting on Kentucky’s Attorney General Daniel Cameron’s lawn after no arrests were made following the police murder of Breonna Taylor.

H.E.R. and Cordae are delineating truth and championing the struggle for justice and radical change. Over Zoom, H.E.R., in her overwhelmingly pink room in Brooklyn, and Cordae, outside his Los Angeles home, reflect on the poignant socio-political messages their songs delve into and how their activism exists inside and outside their art.

How did you guys initially end up connecting?

Cordae: It was over two years ago easily. That’s the night that we cut “Racks.”

H.E.R.: That’s right! I was like, “Who’s this guy? He’s fly. He’s dope.” But I had heard about your music, and then I put it all together. At that time you were one of the greatest up-and-coming rappers—conscious, super lyrical. I could tell as soon as I met you that you just loved music, and that’s how we bonded.

Cordae: It was dope! We was probably in the studio for six to eight hours that day. We probably was just kicking it for, like, seven hours, and then spent like an hour on the song. We were able to vibe in a genuine, organic way. That’s why even through these years and through the next decade it’s always going to be real love, real family.

“Racks” is a perfect capsule of themes significant in both your catalogues—artificial happiness, dealing with social media, and that discrepancy of presenting yourself versus maintaining inner peace.

“Throughout this quarantine everybody is realizing what’s important. There’s no area or space to flaunt anything. Nobody cares about what jewelry you got on, what kind of car you drive. You can’t even get in your car to go see your family, and people are starting to realize that that’s what’s important.” —H.E.R.

H.E.R.: I think the main thing in relation to that song and this time is when we said, “All of them racks and things / They don’t relax the pain.” Throughout this quarantine everybody is realizing what’s important, and that stuff is not important. There’s no area or space to flaunt anything. Nobody cares about what jewelry you got on, what kind of car you drive. You can’t even get in your car to go see your family, and people are starting to realize that that’s what’s important. So we vibed on that level as well, as far as the authenticity thing and what matters to us both. And that stuff is great. Those things are a stamp in a representation of our hard work. But this song really is talking about exactly what’s going on right now. How none of those things ease any kind of pain or struggles that we have.

How did you guys get connected for “Lord Is Coming?” Was faith a major conversation when you got in the room together?

H.E.R.: Actually I wrote it three years ago. It’s a little bit political, but it definitely is about all this stuff that’s happening in the world right now. It’s true as they say, ‘The Lord is coming.’ Everything that’s happening right now, it’s been prophesied. We wanted to talk about the real stuff that’s going on and break it down and talk about all these biblical stories that are relevant to today. It’s never too late to turn around. It’s never too late to look at what’s really going on. Faith is always there. Faith is what holds me together. It’s what gives me hope.

Cordae: What was dope for me was the people that introduced us before that performance was the four guys from When They See Us [the men convicted in the Central Park Five case]. When she hit me up to write my verse for it, I was on the road and we’d just finished watching that on the bus. There was a full-circle moment when I was able to meet the four guys that that was based upon. That even gave me more of an emotional push-up for the performance. “This isn’t important just because we’re live on the BET Awards, but this is going to be something that people are going to be talking about and looking back on ten years from now.”

H.E.R.: When they introduced us after we performed, when we walked up to them, I couldn’t even hold it together because I had just watched the documentary. So when I met them, I couldn’t hold back tears, I started crying, because of the years they lost. Money can’t bring that back.

Can you talk about the process of making “I Can’t Breathe”?

H.E.R.: It happened in the middle of all the protests. It wasn’t even a specific movement or anything that pushed me to write the song. It came straight from the pain of seeing videos online. It wasn’t fueled by anything other than anxiety and pain and worry for Black people. I had actually flown to the Bay Area to be with my family. I’m at home watching all these videos thinking this could be my uncle. This could be my aunt or my sister or my dad. That’s really, really hard to deal with. That’s really hard to comprehend.

“It’s our duty as the new leaders of music to speak on things that are going on in the real world, whether it be through music or through our platform. That’s what we’re here to do, to create change, to inspire, to speak on things that some of our listeners may or may not know about.” —Cordae

I had a conversation with Tiara Thomas, somebody who I write with a lot. She’s like my big sister. It was a good two weeks where that was all we could talk about. Every conversation you had had to be that—it always ended up there. We’d been asking ourselves all these questions, like, “Why is this happening?” One of the lines in the song was a real question that we had, “How do we cope when we don’t love each other? What is a gun to a man that surrenders?” The song really came out of that conversation.

And then, a few days after I wrote the song, I felt there was still more to be said so I put the spoken word on the end. It means so much to say “I can’t breathe.” It’s a tribute to George Floyd. We’re not really free because we’re suffocating and we’re scared. That’s not freedom, living in fear.

Is it challenging for you to be articulate about current events in your songwriting?

H.E.R.: My writing process is all over the place. Nothing is ever easy to write about. Some things are easy because they write themselves. That’s the thing about being creative, you never know what’s going to happen when you step in a room or studio or you pick up a guitar or your voice memos. It can be difficult. Sometimes I have to go through it first, and then write about it, or sometimes I have to be in the moment writing about it. It depends, but everything I write is based on personal experience, whether it’s exaggerated, or it’s plain and simple.

Cordae: You never know what the voice notes—or a conversation—can turn into, like how much music is made based on conversations. The first time we met, before we made any music together, we had really dope, meaningful, genuine conversations. That’s where the best music comes from. It’s the same thing when you’re speaking about world events. It’s our job as artists to create markers in time. That’s always been done in art, from Gil Scott-Heron to Kendrick Lamar. It’s our duty as the new leaders of music to speak on things that are going on in the real world, whether it be through music or through our platform. That’s what we’re here to do, to create change, to inspire, to speak on things that some of our listeners may or may not know about. It’s easy when you reach a certain level to become out of place or disconnected. We have to stay connected with our people and things that are going on on Earth.

Cordae’s music has touched on this but, do you have thoughts on your message and art crossing a generational gap?

H.E.R.: I don’t personally think it’s youth-based. It’s all people of all colors, of all generations. George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Trayvon Martin—that’s three different generations right there. I don’t think just the young people are speaking up. I think all people are speaking up, and all people are changing. But we are the future. So that’s why our voices matter. We are going to be the future leaders. We are the ones that have the voice. We are the ones who control social media. The young people control the culture and what’s hot.

“I don’t think just the young people are speaking up. I think all people are speaking up, and all people are changing. But we are the future. So that’s why our voices matter.” —H.E.R.

I’ve seen other people in different countries put Black Lives Matter outside their windows or paint it on their doors. It’s not just in the U.S., and it’s not just young people. There can be a mentality difference. Honestly, to me it doesn’t matter because we all want one thing, and that’s peace. Every mother wants to see her son come home safely. And every daughter wants to see her dad at her graduation, or at her wedding, and not have to worry about that.

Cordae: When I knew that performance was truly, truly powerful, I was on tour in Europe. I was at the Louvre. A little kid came up to me and was like, “Thank you for showing love to Sudan. That really meant a lot.” That’s when I realized how powerful this music shit was. I don’t think there is no generational gap or disconnect with this issue that is going on right now. It’s bringing more of a togetherness with everything. It’s right from wrong.

H.E.R.: That’s what we said in “Lord Is Coming.” Everybody knows right from wrong. I don’t care what religion you are, where you come from, everybody knows that killing somebody based on the color of your skin is wrong. Regardless of everything going on, we all have this bigger picture of what’s really important. Life is too short. We lost Kobe Bryant this year. We lost Chadwick Boseman this year. Two amazing Black men who inspired a generation. We have to continue to live and walk in our purposes. You never know who’s touched by what you have to say, or your art. When you’re genuine with yourself, you help somebody else without even realizing it. You don’t necessarily have to move intentionally to be intentional and to touch people.

What was the moment growing up listening to music or any type of art that made you realize art and activism, or a message, could coincide?

Cordae: I was, like, five years old when Nas dropped “I Know I Can.” He was teaching us in a super dope, authentic way about our history, to believe in yourself, and know that you can accomplish whatever you want to and know that you come from a race of kings and master architects and mathematicians and scientists, and be proud of that. Also, with Kendrick’s “Alright,” I was protesting when I was in high school about the same issue that’s going on today. We was singing along to that song. That was huge for me.

H.E.R.: “What’s Going On” by Marvin Gaye is one of my favorites. I’m a huge old school head. Every single Stevie Wonder song. There’s this one song called “Village Ghetto Land” on the Songs in the Key of Life that touches on things that we don’t necessarily touch on. There’s even songs like “Love’s in Need of Love Today” that’s so beautifully written. “Hate’s going ’round and breaking many hearts,” that’s a powerful line.

“I was at the Louvre. A little kid came up to me and was like, ‘Thank you for showing love to Sudan. That really meant a lot.’ That’s when I realized how powerful this music shit was.” —Cordae

There’s a lot of songs, to me, that might have been love songs but made it feel like songs for change. One of my favorite songs of all time is a Michael Jackson song, “Earth Song.” He talked about the planet. There’s a lot of animals that will be extinct in the next few years that our grandchildren won’t even get to see. And that’s really heartbreaking.

Aside from being an artist and using a platform, I saw you, Cordae, being a frontline protester. Can you tell me about that experience?

Cordae: It was in Louisville, obviously the situation with Breonna Taylor is going on, and I felt like that was sort of getting swept under the rug. After George Floyd, there was a real big movement, like a shift to where everybody was done with all the bullshit that was happening. But it was for about two to three weeks, and then people were starting to go back to their everyday lives. I was raised by all Black women—my mom, my aunties. When I saw Breonna Taylor, I thought that could be my mom, my cousins, my aunties, so I got really emotional.

And you know, Tamika Mallory of Until Freedom is a real good friend of mine. They told me about what they’re doing in Louisville. We sat on the Attorney General’s front yard of the new house that he just bought. We protested in his yard, and we all got arrested. Daniel Cameron, the Attorney General, he personally called up there to make sure we all got hit with felonies. I wanted to use my platform and to make a statement to let motherfuckers know, like, “Yo, we are not letting this shit go. You have to arrest the cops that killed this woman.”

H.E.R.: That’s why we’re here. We’re thankful to be able to talk about these issues and talk about our experience and our perspective, to continue to spread love and awareness through our music—and continue to heal from our music, because that’s what music does, it heals. It teaches. It makes you happy. It makes you escape, sometimes from the real world, or it takes you to a reality that you may not choose to face, you may not want to face. And I’m really proud of you, Cordae, for doing that in your music and in your personal life.

Cordae: Thank you, sis. And I’m proud of you for always using your platform to speak on what’s going on. It gets tiring speaking on these things—this is some post-traumatic stress shit that we’re going through. It’s a traumatic experience to see people that look like you being killed by the police and nothing is being done about it. I’m proud of you for continuing to use your platform and being a leader. We gonna continue to do this. I’m with you for life. Can’t get rid of me, fam.

H.E.R.: We’re gonna continue to fight the good fight. FL