When Frank Sinatra tells Grace Kelly during the 1956 musical comedy High Society that “You were a little the worse—or the better—for the wine,” he could also be talking about The Pogues’ Shane MacGowan. But tippling is the least interesting facet of the finessed poet-lyricist, one whose Irish bells-and-whistle-filled, picturesque tales of ordinary madness and homespun history made him famous beyond his punk roots. A rebel with not only a cause, but an encyclopedic knowledge of (and a desire to join) the IRA before founding The Pogues and a talent for self-destruction, MacGowan is an Irish literary treasure on the scale of Oscar Wilde, James Joyce, and Samuel Beckett—perhaps all rolled into one, with three platinum Pogues albums and one beloved anthem (“Fairytale in New York” with the late Kirsty MacColl) for his many troubles.

All the more reason that director Julien Temple should film a Shane documentary, the newly-released Crock of Gold. Temple has been around punk’s block as long as MacGowan has—the Class of ’76 that spawned the Sex Pistols and The Clash—and turned his attentions and his camera to that time with Pistols flicks such as The Great Rock ’n’ Roll Swindle (1980) and The Filth and the Fury (2000), to say nothing of 1986’s misunderstood and much-imitated youth-quake musical Absolute Beginners (“La La Land ripped us off a bit,” said Temple).

One perquisite, however: MacGowan made it clear that he didn’t want to speak with Temple despite requesting the director as his filmic biographer. And Temple didn’t wish to do the “straightforward, wrinkly old rock star-in-armchair talking-head” routine that plagues many a rock doc. Instead, Crock of Gold uses aged bits “found from journalists who talked to Shane at 4 in the morning in a bar in Upsala in 1985,” as well as interviewers such as one with Primal Scream’s Bobby Gillespie (whose questions about first coming to London are met with a stony silence), one-time President of the Sinn Féin political party Gerry Adams (to whom MacGowan was adorably reverent), and the film’s producer Johnny Depp, who gets slurrily drunker as their chat goes on.

In the end, Crock of Gold is a poignant, snottily told history lesson about Ireland’s green hills, MacGowan’s mean reds, and the rollicking raw music that acted as their twin soundtracks. FLOOD caught up with Temple to discuss the project.

On a yearly basis in the U.K., BBC Radio 1 insists on editing “Fairytale of New York” due to its homophobic slur. This year Nick Cave came to the song’s defense, stating that such censorship “mutilates” the song’s true intention, its outreach to the world’s outlier, and ruins MacGowan’s poetry.

I completely agree with Cave that it’s horrible to censor anything, really. Then again, it’s not great to insult people’s sexuality, so I do see both sides of the story. An organization such as the BBC has been targeted by the Murdochs and the Daily Mail—they’re trying to take it out, and instead have all these Fox News–type stations replace it—so that’s an Achilles Heel where the BBC’s concerned, a weak point open to attack. Blowing up “Fairytale” and Shane’s circus freak reputation as a Keith Richards–like drunkard and abuser takes away from the real meaning of Shane MacGowan, an attempt to diffuse who he really is. They take away the spotlight from some even-greater songs of his—songs with lyrics even more dangerous and provocative. It’s all good copy for the film, though.

What sort of camaraderie did you witness between Cave and MacGowan, as you focused a lot of attention on those two together at Shane’s sixtieth birthday party, near the end of Crock of Gold?

I find Shane deeply moving, and Nick’s respect for him doubly so. I think, too, that Shane was almost in tears during that scene as he could not believe that he was alive to receive such acclaim. He’s fighting off emotion where he doesn’t really buy into or believe in all of that bullshit. You can’t deny, though, that it is really moving him. He’s Shane MacGowan. It shouldn’t matter, all this wind being blown up his ass. These accolades are for an Elton John, not a Shane MacGowan. But he’s been through a hell of a lot to get there. Nick is attuned to Shane’s emotions in the moment, powerful ones at that.

Did you guys have some long relationship before this? Shane said something about you as the end credits roll, but of course you can’t quite make it out…

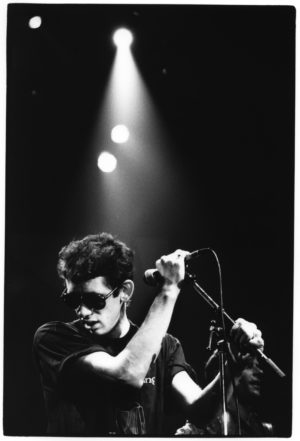

He was being asked what he’d like his fans to take away from the film, and he answered that if it didn’t tell the truth, that’s down to Julien. He said that during an interview with his wife, and I found it funny enough to include. I’ve connected with his music forever, but we only shared that early punk moment where I was filming the Sex Pistols and The Clash peripherally. When Sid [Vicious] left the Pistols and that scene there was a vacancy as the king of the mob, a job that Shane applied for and won. When I was filming, the camera would scan the pogoing crowd and end on Shane MacGowan. He was metastasizing the energy around him.

There was Hiroshima-like radiation hitting this guy, and he was being changed, morphing into different versions of himself as he was listening to the music, taking it in. The first interview ever done with him was me talking to him, the clip we use where he’s got that peroxide-blonde hair. To become a punk, then, everyone had to get the peroxide bottle out, shake it up, and pour it over your head, like Marlon Brando in Julius Caesar. From there, you had to put on the Guy Ritchie Cockney accent to prove you were real [laughs].

“Blowing up Shane’s circus freak reputation as a Keith Richards–like drunkard and abuser takes away from the real meaning of Shane MacGowan, an attempt to diffuse who he really is.”

How did it come about that you would do a film on Shane, and what was his reaction?

Like all good things, it was an accident waiting to happen. He asked me to do the film through a friend of his. I was finishing up a film on Ibiza and couldn’t do what they wanted me to right then.

Moving from the sunny shores of Ibiza to Shane sounds like a dramatic leap.

I needed to think it through. Shane comes with a reputation for not being easy to work with. If he wasn’t difficult, he wouldn’t be Shane MacGowan. You have to wonder if you could take the abuse that’s bound to come. Can I do the film without walking off? Then Johnny Depp got involved, and asked me to hang in there. I felt emboldened by that, as you knew that Johnny could keep it from capsizing. Without Johnny, this film may have never gotten finished. It was important to know that we wouldn’t lose this film in the depths of the Irish Sea, and not be able to salvage it.

So then their friendship is genuine.

Massively so. They connect on many levels, the music obviously being the foundation. Both are into film, both read a lot, both like a drink—what’s not to bring them together? We shot them for eight hours, fell asleep, woke up, and found them still talking. We only used, like, three minutes of their conversation, but they were talking about weird, wonderful subjects. I could make another whole documentary about their conversation regarding Kris Kristofferson on its own. More easily than one on Shane, I can tell you, because he’s constantly warding you off from talking about anything having to do with himself. The first thing he told me about making the documentary was “I’m not doing any fucking interviews. Go away and make the film.”

I won’t bother discussing Depp’s behavior, but there’s a scene apropos of nothing at the beginning of the movie where Shane asks a woman to have “Northern Soul” or “Tamla Motown” music played while he and you talked. She says “no” nicely as they’re filming, and he snaps viciously. And we never see that mean streak again.

I did want to show that he’s got this aggressive behavior, and that it’s very much a part of him. It’s not spoiled rockstar syndrome, although fame is the worst drug he ever took. You know heroin is bad, but you’re not quite sure what fame will do to you. I needed to show it…show all sides, the aggression and that he was a sweet kid born on Christmas Day.

“The first thing he told me about making the documentary was ‘I’m not doing any fucking interviews. Go away and make the film.’”

Making these films is like a mushroom fungus in that you have to find your own way in which the roots run through the story. And what that woman went through was part of my debate in which to do the film with him in the first place. Calling me a “Brit bastard” might have been what others called a “term of endearment.” But in all honesty, that didn’t always feel like the case, especially considering the fact that I never considered myself a Brit. I’m English, I’m not a Scot or a Welshman. This Brit thing relates to the British Empire of which I have nothing to do with, the slavery upon which it was built which I hate.

Being an Englishman, all of the IRA stuff that you reveal about him, those connections—what did you know going in, and how did it all make you feel?

I learned a lot about English/Irish history from Shane. Despite knowing about the eight hundred years of colonialism, I never realized we sent Irish slaves to the Caribbean along with African slaves. I guess I thought Sir Walter Raleigh was a nice guy who just brought tobacco to England and put his coat over a puddle so that the Queen could step across. I didn’t know he butchered women and babies in Ireland. I learned some weird shit about the relationship between Ireland and England from Shane. I had no real understanding of how Irish freedom was won in the 1932 Irish general election. We don’t learn that in school.

I had no idea that every fiber of Shane’s being is electric with his Irish heritage, and that has to do with everything—the culture, the political history, the music, the food, the violence—all heightened by the fact that he’s a first generation Irish immigrant kid in London, speaking and doing just as “Brit bastards” might do. So there’s many contradictions in Shane, sparking and colliding off each other like an atomic research lab inside him. Which is why his music and lyrics are so powerful. They’ve got this fusion and friction of things smashing against each other and creating wonderful new things.

Considering how personal combustion fuels his songs and attitude, I’m curious as to how MacGowan compares with John Lydon, whose exploits you’ve essayed across several films?

“It’s not spoiled rockstar syndrome, although fame is the worst drug he ever took. You know heroin is bad, but you’re not quite sure what fame will do to you.”

Both are incredibly fascinating people who share many experiences, but with totally different backgrounds. John is totally self-taught. Shane went to one of the finest schools in England, a very privileged education. The Lydon family had to live in a beach hut in the winter on Hastings Beach—that’s real poor Irish immigrant experience that creates an attitude, a self-didacticism different from Shane who is immersed in Irish history through his middle class father, Dublin society, and prep schools. What they share is that they are both difficult and righteous people. They can both be generous and both be aggressive.

Then there’s their Irishness and the punk moment. Shane was immensely inspired by John Lydon. The Irish thing cannot be overlooked, as they were crucial to English pop music. John Lennon, Billy Fury, if we can still mention his name, Morrissey. There’s a great deal of Irish presence in English music. What’s different about MacGowan is that he made a real point of being Irish.

Shane’s primary point being to bring Irish traditionalism to the forefront of popular music and punk culture without having to make something modern of it.

John Lennon and Paul McCartney…you wouldn’t know they were Irish. The Beatles were not an Irish act. With Shane MacGowan, there is nothing but “I am London Irish. My roots are Irish. I’m going to give you Ireland. And I’m proud of it.” FL