Lately, I’ve noticed profile pieces on drummers feature a higher percentage of percussionists who have personal recording studios. Home studios are nothing new, but the democratization of materials has birthed a growing community without clear genre borders and without much documentation. There’s been a ton of great scholarship and celebrations of classic, professional recording studios—but even with the catholic interests of Tape Op or Recording Magazines, there’s not been much written about the actual home studios.

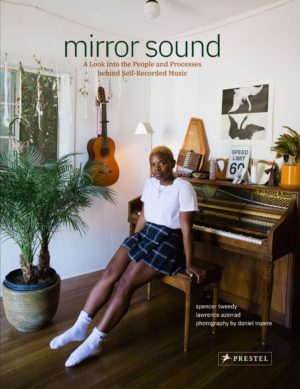

Enter drummer Spencer Tweedy (son of Wilco singer/songwriter Jeff Tweedy) along with designer Lawrence Azerrad and photographer Daniel Topete. Their recent sumptuous coffee table book Mirror Sound is not a how-to—it instead takes a sampling of U.S. home studios from a slice of indie rock, hip-hop, and experimental music and pulls aside the curtain. We see studios as varied as the subjects, some chaotic and some austere. Tweedy’s casual, inviting writing dovetails comfortably with Topete’s warm, candid-style photography.

While even these modest home studios seem materially out of reach to many of us, Tweedy shows us a world where the immediacy between the creation and creator is filed down to its smallest point. The book is an aspirational document and a demystifier—but it will not give you a list of gear or recording strategies. Mirror Sound opens a window into a process that’s becoming essential to a music career. While most of the book is comprised of gorgeous photographs of intimate and sometimes architecturally dramatic spaces, there are extensive interviews Tweedy transcribed about the creative process from all the book’s subjects (and a few others as well). It’s a good gift for an aspiring home recorder.

We caught up with Tweedy shortly after the book’s release back in October to discuss the project and a topic that feels particularly pertinent during a pandemic: home recording.

Is there a way we can dig into drumming and recording drums? I appreciate that this book isn’t driven in that way.

Recording drums is really fun and really hard. The test of a good engineer is the snare drum they end up getting on a recording. The cardinal truth is that it’s gotta sound good in the room.

With drums you have close mics, far mics, and all of these individual pieces of the instrument—but I think the fewer microphones the better. I find myself getting a little bit frustrated when I’m in other recording environments and people are getting out measuring tapes and lasers and trying to perfectly calibrate the location of overhead microphones. That’s totally disconnected from how we actually make the drums sound.

Do you have a favorite drum sound?

I think 1972 is the best year of drum sounds in history—Kenny Buttrey’s sounds on Neil Young records, for instance. Minimal approaches generally feel better to me. As far as the drum tones themselves, I love recording dead drums so they don’t take up a whole lot of sonic space. It doesn’t work in every setting, of course.

The sound that I’m always chasing is the kick drum sound from those 1972 records. There’s a roundness and a certain part of the frequency spectrum that is so pleasing. It even sounds warm and nice on a tiny cell phone speaker. When I was first learning to record at fifteen years old or so, I thought that sound came from analog tape. So I bought a half-inch Otari machine and experimented. There is a low end bump from tape, but that’s not all there is to the story. If I really wanted the drum to sound like that, I realized I would have to make it sound like that [in the room.]

You’ve come up with your father recording. Did that impact the way you think about recording?

Completely—in some material ways and some less material ways. When I wanted to experiment with some more professional equipment like preamplifiers and compressors, there was extra equipment lying around my dad’s studio. I’ve also spent eight years watching Tom Schick, the engineer at the Wilco loft, learning and absorbing the way he and my dad work.

How did you find the artists in the book?

It’s based largely around people who are in the indie rock world, but we wanted to make sure that it wasn’t all guitar music. There are people who are working with different sonic pallets, different ages and ethnicities—not all men. We wanted to make it inclusive because it’s a very inclusive art form.

What are some takeaways you learned you could apply to your own recording?

I was really inspired by people who used improvisation with their recording process like Ty Segall and Bobb Bruno [of Best Coast]. I want to have a vision in mind before I start recording something, but hearing them talk about just sitting down and playing a drum beat for a few minutes and using that for the template that they build new stuff on was really freeing.

I was also inspired by the ways everyone kept themselves going when they felt tired and didn’t feel like working. Everybody feels this way every now and then. It’s encouraging to hear other people talking about how they trick themselves into working again.

You wrote in your introduction about the problem self-recording drummers have running back and forth between the control room and the tracking room. What do you want drummers to get from this book?

The book is not a technical how-to guide, but there are some interesting solutions to that problem in the book. I love recording songs because I can make stuff that’s fun to drum to. That doesn’t necessarily mean the drums are front and center, or that super technical things are going on. It’s not fun making a song unless it has a rhythm that feels good. If there are any drummers who are considering tracking other instruments and building up songs alone, they don’t need to be a super proficient guitarist or pianist. You can build just barely enough skill that is needed by the song that’s in front of you. A lot of the artists in Mirror Sound work that way. If the song calls for a MIDI glockenspiel part, learn the part by ear and tap it out on a keyboard.

Being a drummer puts people in touch with something fundamental to making music. I always think about that possibly apocryphal James Brown story: He would point to each member of his band and ask “What instrument do you play?” The correct answer was “drums.” If they answered anything else he would yell at them. Maybe it’s a little drummer-chauvinist—but I feel that way. People who feel rhythm all the time have a head start on arrangements.

A drummer is an arranger from the get-go.

Yeah, I never thought of it quite that way before. Individual drums can give every facet of a song a different treatment. FL