Once upon a time, in a magical land known as South Philadelphia, Raj Haldar, a gentleman and hip-hop/ambient house fan also known as the rapper-producer Lushlife, began releasing the magically menacing music he mixed in his basement. Starting with 2005’s West Sounds (a Kanye West/Beach Boys mashup), Lushlife dropped a series of mixtapes (his critically acclaimed Cassette City), albums (2012’s Plateau Vision), and collaborative projects (Ritualize with CSLSX and guests including Killer Mike), before releasing one of the first true anti-Trump recordings with My Idols Are Dead + My Enemies Are in Power.

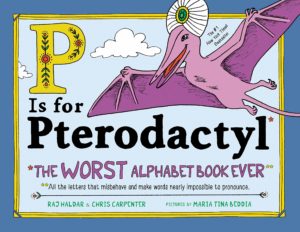

No sooner than Trump was named president, Lushlife grew restless in his South Philly basement, returned momentarily to his given full name, and co-wrote a New York Times kid list Best Seller, P Is for Pterodactyl: The Worst Alphabet Book Ever, with Chris Carpenter and Gorey-like illustrator Maria Tina Beddia. Lushlife’s thrilling ideas for children allowed him to create a script for a horror film soon to go before cameras, a sequel to his children’s book debut in the just-released No Reading Allowed: The Worst Read-Aloud Book Ever, and a new spooky, avant-jazzy EP, Redmancy, whose funky, fresh-faced single, “Depaysement,” makes its world premiere below.

Tell me a little bit about your decision to start crafting children’s books to begin with—do you have children?

It’s funny, my wife and I just had our first baby this April. So my interest in creating children’s books very much predates having a family myself. I started work on P Is for Pterodactyl sometime in early 2017. The concept for the book—a silent-letter alphabet book—really drove the ambition to get it out into the world. It seemed like the perfect kind of idea, where it was both whimsical and absurd and also served a real educational function. When I think about it, there is a throughline, though, between being a rapper and these children’s books. Ultimately, both pursuits are heavy meditations on wordplay. With both of my books, you’ll find that there are maybe only a couple hundred words in the whole book, but it takes many months to really zoom in and focus on the right rhythm and word choice. It’s not dissimilar to how a flow is constructed as a rapper.

How did you, a rapper by day, set about finding the right agents, editors, and publishers for your writing goals?

Finding the right team was definitely the hardest part of my new foray into children’s media. I didn’t know a single person in the book publishing world. I did ultimately know that I could wield my visibility as a recording artist to make the right inroads. I reached out to a magazine founder that followed me on Twitter, and through a couple hops ended up with my now-agent, who herself was once President of HarperCollins. I’d say the rest was history, but from there it took six months of workshopping the manuscript and another year of pitching the book to every major publishing house and getting a litany of rejections. Thankfully, my incredible publisher, Sourcebooks, came along and really got the vision for P Is for Pterodactyl and a whole Worst Ever series.

“When I think about it, there is a throughline, though, between being a rapper and these children’s books. Ultimately, both pursuits are heavy meditations on wordplay.”

Thinking about No Reading Allowed, was there always a sequel involved?

My initial pitch for P Is for Pterodactyl always included a whole section on how the concept of this counterintuitive alphabet book could be extended to a whole world of subjects. Anything in our real world, where kids might find the answers confusing or confounding, seems fair game. For the second book, which came out late last year, I decided to go further down the rabbit hole with zany elements of the English language. This book is all about homophones—words that sound alike but have different meanings.

While there have been a few books that take on this topic for kids, I haven’t seen one that embraces the concept with the sheer level of absurdity that we have, using totally soundalike sentences and showing how they can imply totally different things. One of my favorites in the book is a spread that says, “The new deli clerk runs a pretty sorry store” on the left hand page, showing a flustered kid in a classic deli setting. And on the opposing page, “The New Delhi clerk runs a pretty sari store.” Halfway around the world, in a bazaar in New Delhi, a proud store owner shows his gorgeous, multicolored saris to a young girl.

How do you see the correlation between book creation and music creation? Or, if we take this one step further, serial scriptwriting a la Cult of the Aghori?

As my career has evolved, I’ve realized that my interest in being a musician in my twenties and early thirties was more broadly about the desire to make stuff in general. I just really always took the creative process of ideation, execution, and then sharing that final product with the world. As my career has taken one left turn after another—first into kids books, and now into film and TV—it doesn’t feel like it’s some entirely new ballgame. I’m just applying the same creative drive to new mediums. For Cult of the Aghori, a horror-thriller TV series set in India that I have in development, it took more than a year to even learn the vernacular of scriptwriting, but in the end it’s just like making anything else—you formulate a concept, and then iterate until it feels finished. The trick really is in knowing when something is good enough to be called done.

What can you say about that film’s script, a self-described “social horror” tome?

My older brother and I have always had the idea of doing a horror film set in our ancestral home back in Kolkata, India in our heads. We traveled there growing up on summer vacations, and it always struck me as a place that felt at once deeply at the behest of globalization but also somehow totally untouched by time—a perfect setting for a folk-horror project that touches on caste-class dynamics, globalization, and some pretty terrifying ancient Hindu vampire mythos that still has fringe practitioners there to this day. Seeing films like Jordan Peele’s Get Out and, more recently, Parasite use genre film to take on social issues really galvanized my desire to get this project in motion.

Redamancy is “a love returned in full” by definition. How does that vibe fit the feeling of new tracks such as “Hessdalen Lights”?

I discovered the word “redamancy” written on the back of a stop sign a few years ago. Weird place to learn a new vocabulary word, I know. What’s awesome about it is that it’s the only English word for love that specifies reciprocity. That really struck me. I’ve been making records for most of my adult life now, and I wanted to make this the title of the EP because it’s never lost on me that even a decade plus into it, there is a core audience that is hyped when I have something new to say, and I just wanted it to be known that that love is reciprocated and keeps me going. I hope when you hear the warm horn figures on “Hessdalen Lights” and the gauzy boom-bap of “Depaysement” that sentiment comes across.

“As my career has taken one left turn after another—first into kids books, and now into film and TV—it doesn’t feel like it’s some entirely new ballgame. I’m just applying the same creative drive to new mediums.”

As we’re premiering your new single, “Depaysement,” please tell me the challenges that arose while creating it, and how its intended results feel in terms of your full recorded canon.

The new single is the most direct connective tissue between the Lushlife music that fans already know and the new directions I’m exploring on this EP. It’s a sprawling nine-minute track that lulls you in with some beautiful ambient textures, but gradually morphs into something that feels more like classic ’90s hip-hop. To that end, one of my rap heroes growing up, Dälek, contributed an incredible verse to this song in its second movement, so to speak.

Finally, the last several minutes of the song evolve into an amazing noisy jazz freakout courtesy of the group behind Moor Mother’s Irreversible Entanglements. I got in the studio with those guys before the pandemic, and they played a bunch of amazing stuff over tracks that I had been working on, and so you can hear their playing across the entirety of this EP. And while jazz has been somewhat central to the sound of Lushlife over the years, it’s been somewhat oblique and impressionistic. With Redamancy and the latter third of “Depaysement” in particular, you’re going to hear free, discordant jazz way up front as the fundamental sound of this project.

It’s a decade-plus into your music making career: What does Cassette City sound and feel like to you now, as that was truly the first time many listeners beyond the neighborhood really heard you?

I don’t listen to my own records a whole lot after they’re out there in the world. I’m super proud of each full-length, but putting together an album is such an arduous process, I find it difficult to just enjoy them as a third-person listener. That said, with Cassette City celebrating its ten-year anniversary recently, I’ve seen folks on the internet talking about how the record still hits for them a decade later. Going back and listening is interesting for me, too. Every album is like a time capsule of my life in a certain moment, and that record represents so much optimism about bringing together disparate sounds that I loved into a singular form. It was so maximalist and I did so much orchestration with tons of live instruments and players, from chamber orchestras to professional theremin players across it. With this much distance, I can finally hear it as a listener, and I do feel like it’s aged pretty well.

Considering how many years have passed, what would the adult you say about the 2009-era you—the art you might make and the culture that would follow in its wake?

I think about this a bit now that I’m a dad. My daughter is going to one day listen to my rap records, and as much as I’m pretty thoughtful and erudite, I also have allusions to partying and bullshit that I’ll have to answer for when she can understand what I’ve been on about. Still, it’s just a record of who I was in my twenties, and so in that way I feel lucky to have a life that’s punctuated by these reminders of these little epochs.

“I wanted to make this the title of the EP because it’s never lost on me that even a decade plus into it, there is a core audience that is hyped when I have something new to say, and I just wanted it to be known that that love is reciprocated and keeps me going.”

You hopped on the anti-Trump train very early with My Idols Are Dead. Considering we’re just now coming through a long period of the Donald, how are you?

Holy hell. I started recording that anti-Trump, anti-fascism mixtape the week after Trump won the election. The ensuing four years have been an awful trip, worse still with a completely inept administration dealing with a global pandemic. In this moment, I’m hoping that the current administration, one that at the very least values science, can get the vaccine rollout moving at full tick and provide financial assistance to the millions of Americans that need it. From there, I think there’s bigger reckonings that we as a country need to come to grips with in understanding how we’ve gotten here, and what we need to do in order to move things in the right direction.

In 2021, what are the greatest differences between Raj and Lushlife? Are the divides broadening, or drawing closer?

On the creative side, there’s really no difference between Lushlife the musician and Raj Haldar the author, film and TV creator, and whatever else. Ultimately, if there is any difference of perception there, that’s a marketing question. To me, when I sit at my computer or in my home studio in the morning with a cup of coffee, the raison d’etre is simply to create. I guess my hope is that audiences are able to see all of the stuff I make as part of a single viewpoint and narrative. You know, the weird world of Raj Haldar, I guess. FL