One could always argue the point that since the start of his tenure with Roxy Music in 1972, Brian Eno has been many things to many people—synthesist, singer, producer, installation artist, ambient music avatar, functional sound provider. In my mind, however, Eno—like a Marshall McLuhan or a Jenny Odell—has been nothing short of our era’s most public intellectual, a proactive (and provocative) thinker and doer who’s crafted reasoned, even superior, intelligence in situations where the prevailing common denominator’s rule simply won’t do.

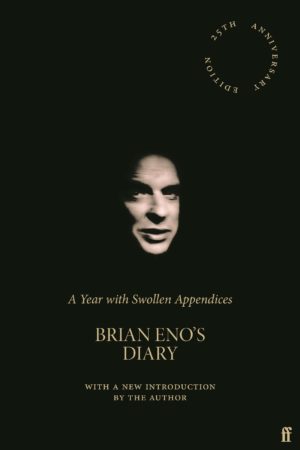

That much of Eno’s fluidly algebraic, imaginative thought is focused on the self (be it the asymmetrically creased ruminations of the newly re-imagined diary A Year with Swollen Appendices, or the first music with his brother Roger in decades, last year’s Luminous) and its most intimate relationship with the outside world (a lifelong career of spare, sinewy sounds and beautifully menacing music for films) is what makes this month’s releases crucial to knowing and understanding him. They are Brian Eno at his most essential, closest to the bone—the utmost Eno.

The title to Eno’s first collective movie music set feels inaccurate without a “Volume 1” attached, as the seventeen tracks of scores and soundtrack slices that fill Film Music, 1976-2020 are but the tip of a very cool iceberg. That said, what is here gracefully acts as a primer to another cinematic layer, or atmosphere, in which a smart director could shift at will, courtesy of Eno’s vision. These musical moments are open and fluid, and can be moved and morphed like chess pieces in space. Even in the case of the neo-bluesy dreamy take on “You Don’t Miss Your Water” (from Jonathan Demme’s Married to the Mob), they are not confined, even if (and when) they add definition or punctuation to a given scene.

Though you can taste the tension between characters set (or belied) by Eno’s twilight mood music for Michael Mann’s Heat, this same sonic slice of stress and strain could have moved anywhere within Mann’s film and maintained its tone of crepuscular menace, sadness, and offbeat machismo. On occasion, this flux actually manages to better even the filmmaker’s best intention, as with the sinisterly spellbinding “Prophecy Theme” co-composed for David Lynch’s Dune, with his brother Roger and fellow producer Daniel Lanois, as well as “Under,” from Ralph Bakshi’s animation/live-action fantasy Cool World, and the only song on Film Music to feature vocals. With its syn-percussion and its ghostly voice, “Under” is so much better than Bakshi’s entire flick.

That Eno is spending so much of his diary’s life commenting on what art and the artist should be, as well as offering commentary on the planet’s violent comings and goings and its more trivial pursuits, is what makes his compositions for film so global.

Strongly influenced by Nino Rota’s music for Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits, where so much of the Italian director’s surrealistic mood is provoked by the composer’s music, Eno’s serene “An Ending (Ascent),” initially composed for the 1989 moon-landing documentary For All Mankind, but also used by directors such as Miguel Arteta, Danny Boyle, and Steven Soderbergh, is proof how one man’s meat (or his synth washes) is another man’s mood-swing. Knowing that Boyle and Soderbergh often work from the sound-ground-up is essential to understanding Eno’s participation—in this and perhaps many other movies. Plus, in the case of the clanging “Top Boy (Theme)” from the British crime drama of the same name, the xylophone-filled ringer makes me want to see the show.

The latter could very well be the case when it comes to director Gary Hustwit’s documentary on Dieter Rams, the German industrial designer, architect, and academic associated with the functionalist school of design, and a less-is-more attitude to unobtrusive motifs. If you closed your eyes and opened your ears, that pretty much defines Eno’s work. With that, the composer-producer’s score to Rams is an open-ended, faux bell-and-gong-tinging delight, something that, on a lovely moment such as “Design as Reduction,” comes across as somewhat Tibetan/Buddhist in its quietly trembling tone at its start, but blossoms into something ever-so-slightly aggressive by track’s close. That this holy roll accompanies a most intimate portrait of an iconic designer is followed by aptly titled tracks such as “Bright Clouds of Metal,” “Harmonic Guitar,” and “Designer Piano,” all while pursuing vibrant still-life melodies on the likes of “Generative Lounge,” makes for one quietly adventurous thrill ride in accordance with each artist’s “Design as Reduction” ideal.

All of the ideals behind Eno’s experimental conceptualism—from film scoring to Fripp collaborating, from generative music to Jah Wobble, from director Derek Jarman to genre-jumping David Bowie—can all be found in the 25th-anniversary hardcover edition of his diary, only now with fresh bonus forwards and other new “appendices” to bring it into the present and future. That Eno is spending so much of his diary’s life commenting on what art and the artist should be (then moving toward such change, driven by the likes of Marcel Duchamp’s found-object aesthetic), as well as offering commentary on the planet’s violent comings and goings (from crises in Bosnia to the Oklahoma bombing to Brexit) and its more trivial pursuits (goofy passages about passing gas and artists’ royalties), is what makes his compositions for film, for example, so global. The Tibetan feel on a film track such as “Design as Reduction” can be traced directly to something worldly and spiritual (as opposed to religious, of which he is specious), as well as his proclaimed love of Fela Kuti, or his charitable concerns about the children of Bosnia.

While Eno concentrates his new writings on new words and phrases (“cancel culture,” for example) and the ever-changing purposes of language with fresh purpose (“Is binge-watching Netflix the future of art now that galleries have become dangerous” in the throes of COVID?), its one of his past statements that resonate with who he is as an artist, a composer, and a manufacturer of bold and subtle atmospheres ripe for cinema.

“Generally, my feeling is toward less: less shopping, less eating, less playing by rules and recipes. I favor more thinking on the feet, more improvising, more surprises, more laughs.” That’s an Eno work for sure. Or at least the start of a dozen greater ideas. FL