My adventures with warbling-voiced, Venezuelan-tinged, free associative poet and lyricist Devendra Banhart’s work started with Michael Gira’s suggestion that I check out his latest find (2002’s fragmented Oh Me Oh My), winds through Topanga Canyon at manager Eliot Roberts’ urging (for 2005’s Cripple Crow), and ends up sitting calmly with the singer-songwriter’s last three sparer—but no less surreal—efforts (2013’s Mala, 2016’s Ape in Pink Marble, and 2019’s Ma) before gazing up at his latest creation-curation, The Grief I Have Caused You.

This IRL and virtual exhibition of his art—taking place at Nicodim Upstairs in Los Angeles, and standing until March 20, in addition to being accessible online—is not Banhart’s first rodeo where sensual, silly visual art is concerned. Along with drawing and painting the majority of his LP sleeves since his start, Devendra has contributed to Doug Aitken’s multimedia Station to Station project exhibited with other artists in Italy, San Francisco, and Queens, and his monograph of drawings and paintings I Left My Noodle on Ramen Street was published in 2015. The Grief I Have Caused You, however, is Banhart’s first solo art show, an event we discussed as Valentine’s Day was only just starting.

“Visual art came to me through the unconscious absorption of architecture and nature—that was an obsession, the only art that you could see in Caracas,” says Banhart of his start. “I was born into a time of total chaos—economic, political, and humanitarian horror—right at the end of any cultural movement, and there were no galleries there when I was there. Just buildings, which were quite beautiful, a few kinetic sculptures bleeding through the city, and nature; the exception being Carlos Cruz-Diez, whose work was painted onto the streets. It was as if a fleeting few flowers, a representative of consciousness, were sticking through the fields of green.”

Anyone who knows the Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles knows Cruz-Diez’s work, as one of his most vibrant pieces exist there. “When I first walked there, I got dizzy and nostalgic, it was so powerful,” says Banhart.

Other equally heady influences emerged to affect Banhart’s visual language as much as they would his musical and literary ideals: director Robert Frank’s Pull My Daisy and its take on Beat writing (“Are grilled cheeses holy? Are cockroaches holy?”), the colors of Joan Miro, the creatures of Rufino Tamayo, the thick, squiggly lines of Carroll Dunham, the psychedelic sunbursts of Judy Chicago, and the Mission School in San Francisco all left deep marks on Devendra; as deep as those spirits who haunt and linger with him such as the Tibetan, Nepali, and Bhutanese tonkas and Tantric Buddhist imagery and Japanese floating world imagery. “These inspirations are all explicit in my work.”

“Most of the paintings are just me trying to crack myself up. I’m so horrified and depressed. I have to paint disco bears over the ocean just to cheer myself up.”

Other than ink and oil versus strings, skins, and laptops, nothing separates his visual from his sonic work. “They’ve only been parallel disciplines that meet when it comes time to make, say, an album cover,” he says. “Just like making a record, my paintings and drawings—half of them are characters, half of it is made up and just trying to be self-referential while not exactly being me. Some of it has nothing to do with me or baring my soul, and some of it is extremely intimate. Most of the paintings are just me trying to crack myself up. I’m so horrified and depressed. I have to paint disco bears over the ocean just to cheer myself up.”

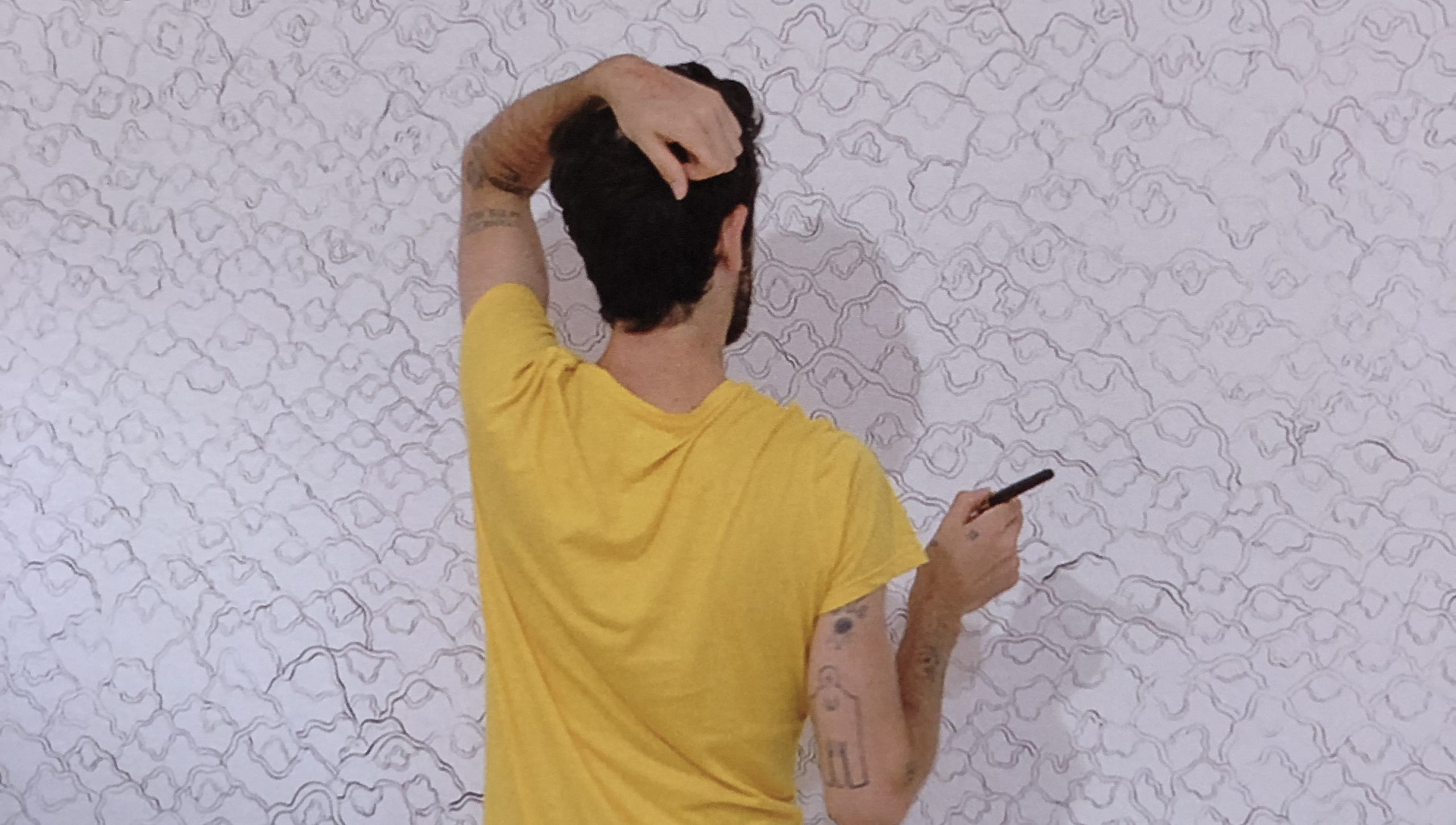

What morphed in order to get him to this current exhibition was the desire to get to the end of the repulsion and despair that is this current time period. “I’m drowning in despair, the reality of this uncertain time—a new texture of depression—so you paint or draw your way out of it.”

The other reason Banhart claims to have waited this long for a solo show is that the stigma of a musician also making visual art has lingered throughout his tenure as an artist. “Galleries pretty much shut the door in my face for over ten years, the same way labels did when I first started out making music. And just like music, it was nice, after so many years, that somebody opened a door and replied. I actually had given up on getting a solo show of my work, and just kept painting—which is exactly when it all came to fruition for me to get my own show. It’s funny how things work out.”

“It’s nice seeing people experience the work without any preconceived notions or baggage—so many people only just found out that I am not an Indian woman.”

Banhart adds one quick, funny thought to this display and discussion of The Grief I Have Caused You exhibition. “Then again, perhaps I haven’t been that good of a visual artist,” he says with a laugh. “You always have to leave room for that possibility.”

Considering that this exhibition—outside of its virtual iteration—is distanced and sparsely attended allows viewers the opportunity to truly see that which Banhart is making apparent. “It’s less of a party setting than most exhibitions,” he says. “I always know that whenever I go to an opening, I have to come back later to actually see the work. This time, now, you can concentrate. You can connect with the work. It’s far more intimate. Plus, it’s nice seeing people experience the work without any preconceived notions or baggage—so many people only just found out that I am not an Indian woman.”

With that, Banhart discusses a few of the objects that line the walls of The Grief I Have Caused You, the collaboration with Nicodim Gallery. Most of the pieces were crafted throughout 2020 and 2021, and the exhibit includes some of his earliest works in oil (“Because I’m rarely home long enough to paint”), several of which have no title as yet.

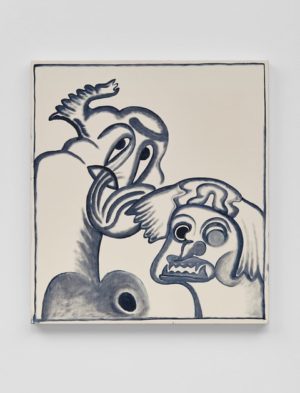

“Niama and Dawa,” 2021

Banhart: That is, I hope, a look at funny repulsion. This painting is a direct reference to a particular Japanese print of two lovers, pretty much a copy. The original print itself is very famous, very ubiquitous in Japan. They’re very beautiful. Very tender, sharing this nuanced love, so I made it…horrific; horrific to the point of having just a modicum of humor.

There is an illustration without a title that looks like two triple sets of legs in high heels. Or flowers.

Banhart: That was certainly influenced by Judy Chicago. Very much so, and explicitly, I’m embarrassed to say. Maybe I’m showing all of my cards here. I like this idea of a disco mandala emerging from the dark.

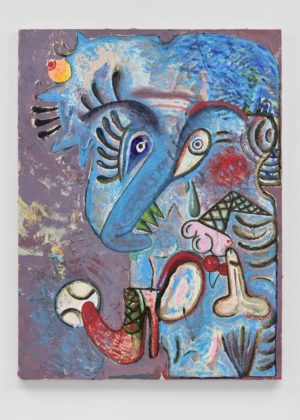

There is a painting with no title, with splotches of red that looks like an angel with a pompadour jumping into a high heel.

Banhart: That is the naked bear-creature doing a disco dance over the ocean. I’m painting until I hear some sort of music; painting until I hear laughter; painting until I feel a little bit better. This is kind of a lowest rung of consciousness in terms of how little it tries to hide what the image represents. There is an ocean of despair, and I’m just painting this free, naked, dancing creature just trying to get over the darkness. It’s really dumb, but it is utilitarian in its stupidity. I love your pompadour description, too.

“Barbarous Nomenclature,” 2021

Banhart: That was originally going to be the title of this new show. This painting is maybe the very first of this series where I worked through its creation, worked through something. I didn’t really stop painting this piece until the repulsion became comical to me. The fact that there are sports involved is personally quite funny because that was a huge source of shaming when I grew up as an effeminate boy with a strange name in Venezuela who couldn’t give a shit about sports. It’s hilarious that I threw that in here, a nod to my youth. That’s also the most worked on painting until that initial wave of disgust and repulsion turns into something relatively comical. I also like the idea of the expressions of these portraits trying to…this is the liminal, borderline state between agony and ecstasy. Is it disgust, or a blissful moan state? That’s the goal in terms of every single portrait in this show. FL

Browse some more of Banhart’s untitled works below.