When Billie Holiday died, police officers watched over her. Lying in a hospital bed, she was handcuffed and placed under arrest. Despite being sick and put on the hospital’s critical list (she was later removed), Holiday was denied access to vital medical treatment. Her friends couldn’t see her. She died alone, written off as a long-suffering addict who passed away due to the side effects of her lifestyle.

The truth? Lady Day was tired of federal agents. She was tough, but as Alice Vrbsky, her friend and personal assistant, later described to the BBC, “this was the last straw.” For over twenty years, government spies hunted her down. No matter what she did, they showed no signs of leaving her alone. This Friday on Hulu, The United States vs. Billie Holiday explains why. Directed by Lee Daniels and starring Andra Day the film is based on the book Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs by Johann Hari.

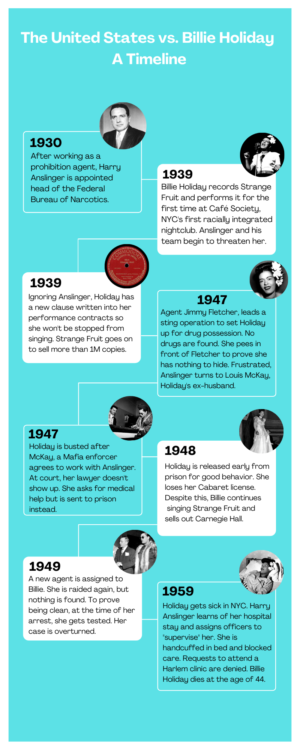

In 1939, Billie Holiday sang “Strange Fruit” for the very first time, and Harry Anslinger, the head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), was pissed. Holiday chose to sing the anti-lynching song live at Café Society, New York City’s first racially integrated nightclub. The song hauntingly compares Black bodies to fruit hanging from trees. Holiday had strict rules in place while performing the song: waiters were not allowed to take orders, the lights were switched off, silence had to immediately follow, and it always had to be the last song she performed. The Baltimore native was rejected twice before being able to record it. After her performance, threatening messages were sent to Holiday. But the song kept growing in popularity, eventually selling over one million copies.

Holiday didn’t actually enjoy singing “Strange Fruit”—it was dark and painful. But she felt the song was too important to keep to herself. It reminded her of her father who died in Texas after being denied medical care at a whites-only hospital. Also, Holiday wanted to consistently sing in front of racially mixed audiences. She wanted Black people to have the freedom to enter venues without fear, and watch her perform from any section. Singing “Strange Fruit” was a way to demand better. Holiday refused to sing in spaces where she was not allowed to perform the song—she had it written into her contract. It became a non-negotiable. And so, Anslinger decided to wage war.

Ms. Holiday did suffer from drug addiction. But that’s not why the FBN considered her a problem. Holiday flaunted her wealth. She dressed well. She had white friends and business associates who worked for her. She travelled. If she didn’t agree with something artistically, she spoke up. Holiday was a public figure who was bold and unbothered. She was starting to use her fame to protest violence and challenge systematic racism. To do that as a Black woman in the 1930s and ’40s was unheard of. Harry Anslinger believed she was setting a bad example, so he assigned an undercover agent named Jimmy Fletcher to track her moves and eventually set her up.

Anslinger disliked hiring Black agents like Fletcher. However, he needed a major win: alcohol just became legalized. In fact, even after Fletcher started working at the Bureau, Anslinger did not allow him “upstairs”—he, along with the other eight Black FBN agents, could only work in the Bureau’s basement. At the time, Anslinger was a young, freshly appointed director for a brand new federal department. At 38 years old, Anslinger wanted to make a good impression as a leader. He could no longer send agents to chase after alcohol contraband and his previous attempts to organize a mass round-up of Black jazz musicians like Charlie Parker or Louis Armstrong for possession of “reefer” had failed.

So Anslinger gathered his resources together to target just one person instead—Billie Holiday. It took at least three raids, two undercover agents, planted drug evidence, multiple arrests, associates who became paid informants, blocked access to lawyers and medical care, a prison sentence, the loss of her cabaret license (required to perform at the time), and two court cases for Anslinger to corner Holiday. And yet, despite the federal witch hunt, she would not stop singing “Strange Fruit.”

After performing at the Mark Twain Hotel in San Francisco in 1947 she was raided in a sting operation set up by Colonel George White, a different narcotics agent who was favored by Anslinger. The day of her arrest, Billie checked herself into a clinic to prove she was clean. At her trial in 1949, she had a lawyer and was found not guilty. However, the very first trial she endured in 1947 did enough damage. “It was called ‘The United States of America versus Billie Holiday,’” she explained in her memoir, “and that’s just the way it felt.” Her lawyer didn’t show up, so she ended up representing herself. “I want the cure,” she said to the judge. Holiday wanted a hospital, but was instead sent to a prison in West Virginia.

Serving time and losing her cabaret license was still not enough for Anslinger or his agents. In 1959, as the Lee Daniels film demonstrates, officers were sent to Billie Holiday’s hospital bed. Lady Day was already sick from cirrhosis of the liver, but Anslinger wanted to ensure that her chances of recovery were slim. When Holiday started to get healthier, her prescribed medication was abruptly stopped. She was denied visitors and access to rehab. Just before she died, Anslinger’s team took her fingerprints and mugshot. She was interrogated without a lawyer from her bed. Outside the Metropolitan Hospital in New York City, fans protested, “Let Lady Live.” While Harry Anslinger ultimately did succeed in isolating and punishing Billie Holiday, it was short-lived. Her courage outlasted his cruelty. She did not back down. He could not kill her legacy. FL