There are a dozen powerful, socio-politicized scenes in director Regina King and screenwriter Kemp Powers’ One Night in Miami, the dramatic film reliving the friendship among Black cultural giants Jim Brown, Malcolm X, Cassius Clay (right before his conversion to Islam and adoption of the name Muhammad Ali), and Sam Cooke.

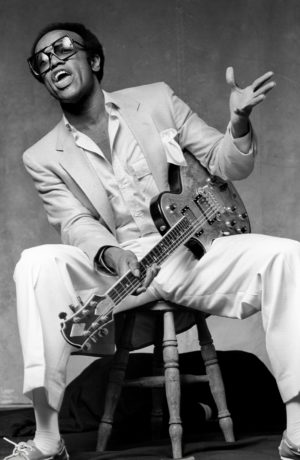

While each man gets his punches in, and knife-like soliloquies heard, the most powerful of statements come from Cooke—as played by Leslie Odom Jr.—when discussing what the singer-songwriter had done for the then-burgeoning Black empowerment movement. In particular, after Malcolm X (Kingsley Ben-Adir) has accused Cooke of pandering to white audiences of the time while leaving Black crowds and fellow musicians behind, Odom’s Cooke roughly recalls to X that he runs a Black-owned business that’s wisely “invested in the British Invasion.” To that end, Cooke not only brings up his own label and his own publishing company, but focuses on The Valentinos—protégés in “five Womack brothers,” the youngest of which, Bobby Womack, wrote this song, “It’s All Over Now.”

Extolling the virtues of The Valentinos’ original recording and its place on the pop charts (“Even made it to #94”) beyond R&B, Cooke then goes on to remember a phone call from England, from The Rolling Stones wishing to record Womack’s track. Despite Bobby’s protests, Cooke—Womack’s publisher with “the final say, looking at the big picture”—gives his permission to the Stones to cover it. History tells us that the Stones’ rough pop version of Womack’s song was their first #1 on the U.S. pop charts. Sure, Bobby’s version falls off all the charts, and he’s crushed—that is, until he gets his first royalty check. “Every time some white girl buys a copy of that single she’s putting money into my pockets. Our pockets.”

Bobby Womack’s pockets. To that end, The Rolling Stones are working for Cooke and Womack. “Next thing you know, Bobby is asking me, ‘The Rolling Stones want to cover any more versions of my songs?,” laughs Odom’s Cooke with pride. “Know who gets more money than the writer of the song at #94 on the charts? The writer of the #1 song. I already knew that. Now Bobby knows that… Tell me how that’s not empowerment.”

“That song, The Valentinos’ 45 RPM, was given to me and Keith [Richards] at a party at Bob Crewe’s Dakota apartment by Murray the K,” Andrew Loog Oldham, the Rolling Stones’ manager-producer and the one-time tour PR agent for Sam Cooke’s lone UK tour, tells me. “Murray told us if we record this with the boys, you will have a hit. We recorded it ten days later at Chess Studios in Chicago. And he was right.” Without making a single visual appearance or playing a single note, Bobby Womack became a centerpiece of one of this season’s hottest, smartest films.

The Valentinos

Womack’s own twisted tale sounds cinematic, though more like a cautionary tale of sexual abuse and drug addiction than anything noble. After Cooke was murdered in 1964, Womack married his widow mere weeks after the singer’s slaying, becoming a faux father to Cooke’s 11-year-old daughter, Linda. A few years later, the widow Cooke caught Womack in bed with the 17-year-old stepdaughter, and he himself got shot for his despicable deeds. From that moment, Womack was all but blacklisted and blackballed, a condition that did not curtail his rabid cocaine use.

“Womack was an incredible talent. The way he cut tracks was an education.” — Andrew Loog Oldham

For a decade or so beginning in 1965, he went undercover, playing with Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Alex Chilton, and Joe Tex, becoming a part of Chips Moman’s American Studios before Wilson Pickett picked up Womack’s gauntlet as a songwriter and released hits such as “I’m in Love” and “I’m a Midnight Mover.” Though he dropped his first solo album, Fly Me to the Moon, in 1968, and made hits throughout the ’70s, Womack’s music and his career were iffy propositions that rose and fell like high tides. “When I first met Bobby in Los Angeles at his house for lunch, I thought, ‘This man does not eat lunch often,’ says Oldham from Colombia. “Marching powder was leading his life, as it was for so many of us.”

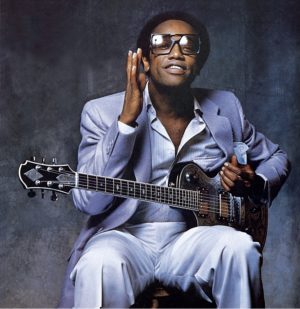

Oldham went on to say that ABKCO label owner Allen Klein had once hired Oldham for Womack, “less as a producer, and more to mind the store. I asked Lou Adler for his take on Womack and he told me to make Bobby play the guitar more than he would want to.” The road of bad intentions of the ’60s and the ’70s paved the way for the singer, songwriter, and guitarist’s greatest triumphs, the back-to-back releases of 1981’s The Poet and 1984’s The Poet II, smoldering, stately samples of what Womack could do as a rough-edged vocalist and even rougher songwriter with the pain of abuse, and the strains of love and loss that had befallen him.

Though seemingly unconnected to Cooke, their appearance now—re-released last week—is keenly timed to One Night in Miami’s success, as well as The Poet’s 40th anniversary. With that, the manner in which he had taken full control of his own career and sound by the ’80s (he alone produced The Poet and co-produced The Poet II with Oldham) is certainly influenced by Cooke’s own discipline, while maintaining Womack’s longtime aesthetic of bruised lover machismo. “Womack was an incredible talent,” notes Oldham. “The way he cut tracks was an education.”

Says Cooke documentarian Mary Wharton, “I think Bobby learned so much from Sam, who really took Bobby under his wing and mentored him. Bobby’s voice was nothing like Sam’s, so he had to develop his own sound and his own vocal style, but he certainly learned a lot about songwriting from Sam. He talked about how Sam taught him to listen to the way real people talk, and to use that as source material for his songs. I think that one of the overriding characteristics of Bobby’s work is how real it feels. The characters in his songs feel like regular people experiencing real pain or actual joy—there’s a truth in all of it that comes through, and I think that’s what people respond to.”

Womack’s incredible talents—from his gospel roots to his time as rhythm and rock collaborator and soul-stirring songwriter—are on full display on both new Poet reissues, despite (or maybe because of) the conflicting emotions and conflicted relationships throughout both albums. The violent death of his brother as emoted through the sober processional melody and churchy choir of “Just My Imagination,” the sensual sanctity of “Secrets,” the jazz-disco-jam of “So Many Sides of You,” and an aging Lothario’s look at mature romanticism and righteousness make The Poet but one peak of the Womack mountainous range. The Poet II is a more dedicatedly feminine recording with songwriting assists from his stepdaughter Linda (“I Wish I Had Someone to Go Home To,” co-written by her husband and Bobby’s brother, Cecil), and guest appearances from Patti LaBelle.

“I think that one of the overriding characteristics of Bobby’s work is how real it feels. The characters in his songs feel like regular people experiencing real pain or actual joy—there’s a truth in all of it that comes through, and I think that’s what people respond to.” — Mary Wharton

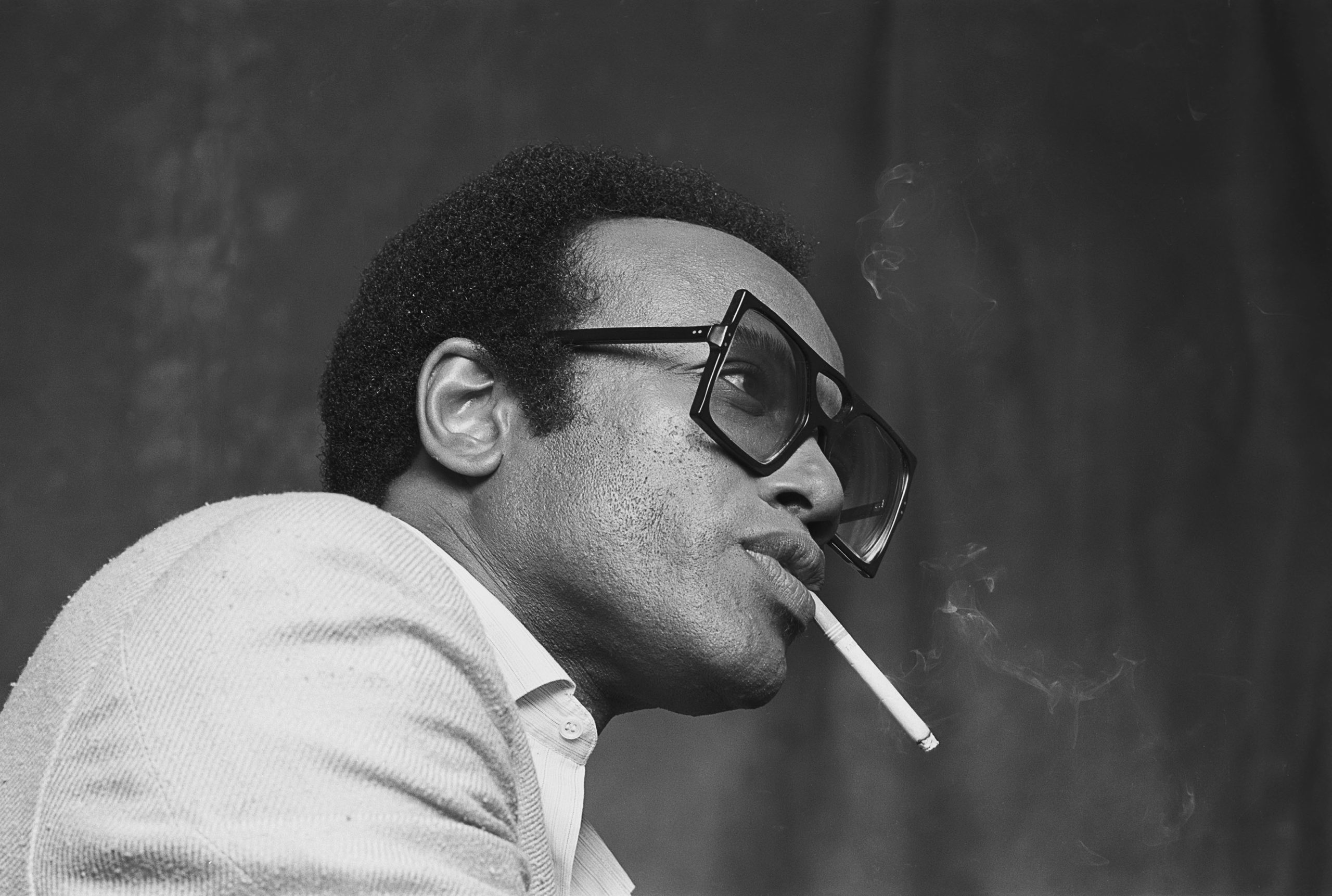

Wharton, director of the 2003 documentary Sam Cooke’s Legend, thought so highly of Womack in relation to Cooke that she not only interviewed Womack before his 2014 death, but included Womack on the poster for Legend in tribute to their camaraderie, doubly fascinating as you never see Cooke beyond his usual, solo, swinging singer. “That’s true,” says Wharton. “You hardly ever see photos of Sam working with other musicians. That photograph was originally taken for a cigarette ad, which is why it is so perfectly lit and composed with Sam in the center, and all the musicians gathered around behind him. It was such a different time, and if you think about the fact that studio time was precious back then, and expensive, so artists probably would not have wanted to be distracted by a photographer while they were working.

“A large majority of the photos that exist of Sam are kind of posed and intended for publicity purposes,” she continues. “There are very few ‘documentary’ style photos of him. The exceptions that jump out in my mind are a series of photos from the recording session that Sam did with Muhammad Ali, where you see Sam working with Cassius on the song that Sam wrote for him. Clay was such a big star at that point, and it would have been super notable that he went into a recording studio with Sam, so that helps to explain why someone wanted to document it. But I remember we struggled with the fact that we didn’t have more images of Bobby and Sam together when we made the film.”

Wharton notes that, during Legend, the “amazing writer Peter Guralnick, who had been working on a book about Sam for years at that point,” was the one who actually interviewed Womack. Though guarded at first while on camera (“He wore sunglasses the whole time, so that tells you something”), Wharton ruminates on how raw Womack’s feelings for Sam were, even decades after his death. “I don’t think anyone in Sam’s life ever got over his death, Bobby was no exception.”

Despite the continued feeling of loss over Cooke’s passing, Womack had a fun story about Sam sending him and his brothers money to get out to California from Cleveland. One of his brothers decided to buy a flashy car instead of something dependable, and the car kept breaking down the whole way. “It took them two or three weeks to get to California, and everyone thought they had died or something, and when they finally got to Los Angeles they were out of money and out of gas and they had to push the car down Hollywood Boulevard.”

Like One Night in Miami, the best thing about the manner in which Wharton presented the intersection of Cooke, and ultimately Womack, is its straight-ahead feel, one without flash. Like Womack’s own lyrics, the language of Legend’s narration is conversational and cool. “Ultimately, though,” says Wharton, “Sam Cooke and Bobby Womack were such insanely compelling characters who were so earthy and real that they were simply timeless in the best sense of that word.” FL