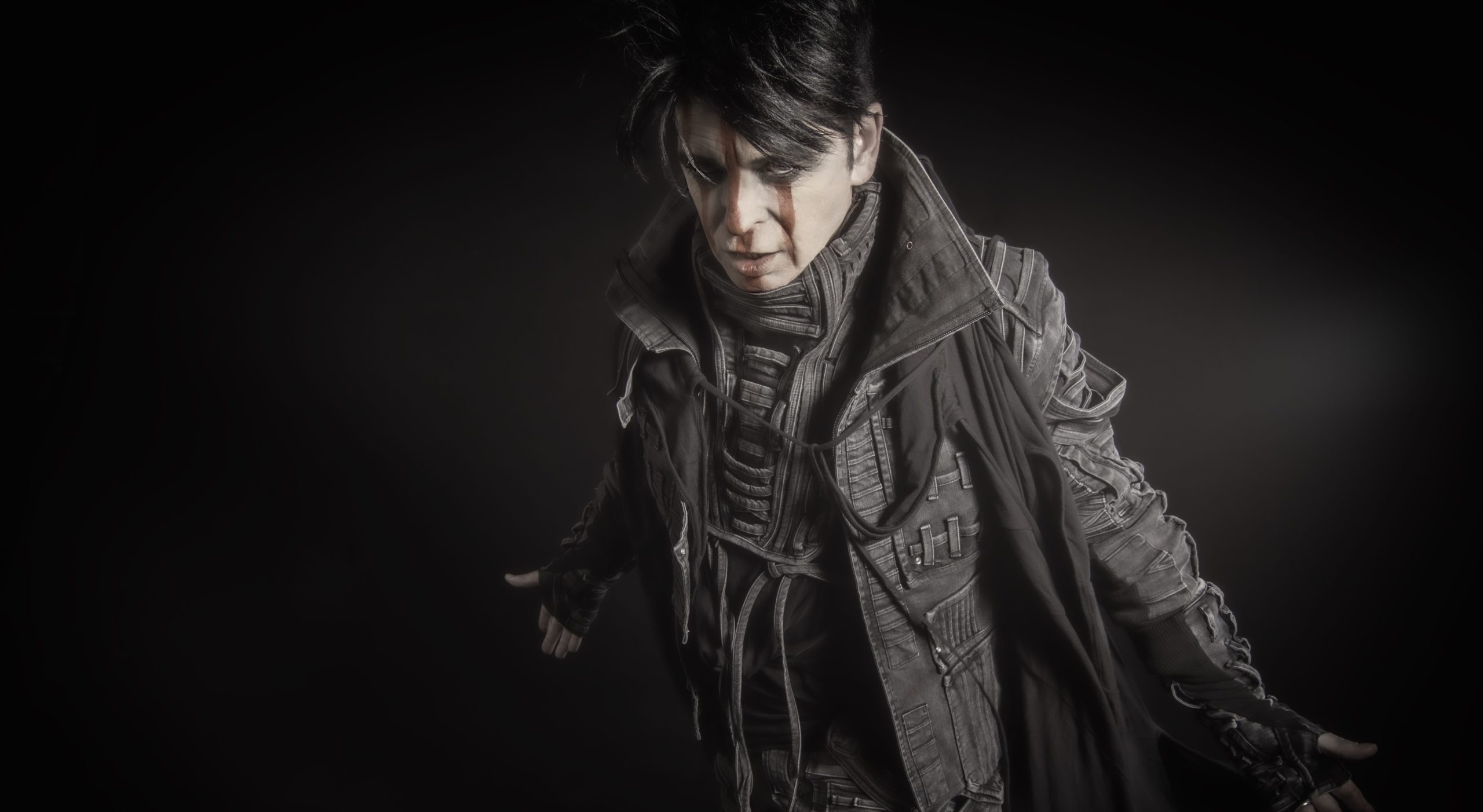

If the planet had a voice, what would it say? That’s the brooding theme of Gary Numan’s latest effort, Intruder, the follow-up to 2017’s Savage: Songs From a Broken World. Once again, the electronica pioneer has become a conduit of sorts for mother nature, who he believes is lashing out on mankind. If Broken World was Numan’s forewarning of humanity’s fall into a “savage” dystopian future caused by the effects of global warming, then Intruder serves as his brutal examination on what nature might do—or is already doing—to course correct that dark outcome.

If you’ve been out of the Numan loop for the past two decades, you’ll be surprised to find that his latest works are a far cry from the early synth-pop days when he sang about cars, films, and robots. Gone are his synth-laced disco anthems and his glam-pop poster boy looks. Intruder, instead, further explores Numan’s evolving brand of industrial, cinematic soundscapes. His textural stamp on the genre combines swirling mechanical beats incorporated with ominous orchestral sounds, distorted guitars, choral voices, and Middle Eastern motifs—think of it as Nine Inch Nails meets Dead Can Dance. And, of course, there’s his unique synthezoid-like voice. On Intruder, we get his classic android persona, only this time he’s observing, analyzing, and processing the actions of mankind and predicting their inevitable downfall.

But still, no matter how progressive his sounds and planetary viewpoints are, he still can’t escape the shadow cast by two of his biggest hits of the 1980s. Despite some highs and lows throughout his tumultuous 40-plus year career, Numan remains confident about his musical future. We recently chatted with Numan, who not only talked to us about the thought-provoking, existential themes that influenced his new album, but also opened up about the daunting and emotional task of writing his recent autobiography, his unapologetic feelings on religion, and coming to terms with the love/hate relationship he’s had with his most iconic tracks.

Before the pandemic, it was announced that you were part of the now-cancelled Cruel World Festival which also included Morrissey, Bauhaus, Blondie, and Devo. You’re known to mostly steer away from ’80s nostalgia trips—what was it about this festival that made you sign the dotted line?

The reason I went for that one was because all those people are still current and they’re still making new albums. This makes me sound like I’m being arrogant or elitist, and I don’t mean it that way, but it felt to me as if Cruel World was just on the right side of acceptable. There are other festivals that have people who really haven’t done anything since the ’80s. Those are to be strictly avoided. There was one that I was going to do in Europe, just before the pandemic, and I had to pull out because they lied to me. They sent me a list of the other bands that were on it. I said, “OK, there’s some really good industrial people.” And when they sent me the artwork for the advert, it was just all old school ’80s people. I’m really serious about the look of these things, and not being tied to that era.

I know you have your own home studio, but did this pandemic affect the making of Intruder? [Producer] Ade Fenton lives in the UK, you’re in Los Angeles…

Normally, the way we work is to simply exchange files. This is the fifth album that we’ve done together, so we’ve been working this way for quite some time. We never sit in the studio together until it comes to the final part of mixing and mastering. So it didn’t really change anything. When the pandemic itself hit, I was about three quarters of the way through, but the not being able to travel thing—it really didn’t have any effect on me at all, because I was deeply locked into the album and trying to get that finished. And then I wrote my book in April, May, and June. I had about nine weeks or so to finish the album, and I had two or three songs left to do. I was just coasting toward the end of it. The book was actually going to be written by a ghost writer, which is a bit of a cop out, but I just didn’t have time.

“I think we’re shaped so much by the negative things that happen to us. If you come out at the end, and are still a good, decent, reasonable, tolerant person, then you’ve handled life pretty well.”

So your autobiography was originally written by someone else?

I got the first draft of the book, and it just wasn’t what I wanted. Everything about it said, “Well, that’s not me—that’s not how I talk, that’s not how I think.” So I said, “I’m going to have to do it myself.” I stopped work on the album and I spent the next seven-and-a-half weeks working on the book. By the time I’d finished, I only had 10 days left to do two-and-a-half songs. All of a sudden it went from no pressure to intense pressure for about two months to get both these projects finished.

Was it liberating for you to finally write your life story and share it with the world?

The making of it didn’t feel particularly liberating, it was actually really quite depressing at times. When you go back over the good things that happened to you, in a way, I think our nature is to take those things for granted. When something bad happens, it really hits us, and it can knock you back for weeks, months, even years. The way we deal with setbacks and disappointments is a much greater test of your moral fiber. I think we’re shaped so much by the negative things that happen to us. If you come out at the end, and are still a good, decent, reasonable, tolerant person, then you’ve handled life pretty well.

While doing the book, it was interesting to revisit all of those heartbreaks. You sort of forget, because you’re always thinking about tomorrow, and you’ve got your children and everything’s good now. You forget what you went through to get there. I remember, one day was spent mostly talking about how our first baby died before it was born, so that was pretty horrible. When I had to go back and write about all that again, I cried. So a lot of it was actually pretty emotional.

On your new album, when you listen close to the lyrics in “The Gift” it sounds like it was heavily influenced by the coronavirus, as if mother nature was getting its revenge on mankind.

That was the one I did pretty much after the pandemic hit. The whole idea of Intruder is, I’m meant to be speaking as if I’m the earth. When the pandemic hit, it just perfectly fed into exactly what the album was talking about in a horrible, sort of tragic way. If the earth fought back, how would it do it? Viruses would seem to be a fairly obvious choice. Nature uses viruses as a system to control itself, but it makes mistakes. The more I talked about Intruder, it seems to me that I’ve come to believe that human beings are one of the very rare mistakes that nature has made. I think it made us too curious, too inventive, too intelligent, perhaps, too greedy, too selfish. I think it just gave us a little bit too much of everything apart from sympathy, empathy, respect, common sense, and understanding.

Chris Corner of IAMX seems to be your go-to guy for music videos. Does he come up with all these concepts on his own, or do you two just toss ideas into a melting pot?

Chris is an absolute genius when it comes to videos. He’s done four for me now. I’m honored that I’m one of the few people that he actually does videos for. I always send him the music and the lyrics and a write-up on what the song is about and what the intention of it is, to make sure it’s clear. Then he just comes up with a visual interpretation of that. He goes out and takes photographs and sends me notes. I can then make comments or change if I want to, but he’s so clever and so visually orientated. He’s the whole package: a great songwriter, an amazing singer. And as a video maker, I don’t think there’s anyone better.

You posted about the concept of the “Saints and Liars” video on your Facebook and explained how it’s about the hypocrisy of people worshiping a non-existent god, who does nothing for us, yet we hurt the planet, which does everything for us. Are you aware that you ruffled some feathers with that post?

I assumed it would. I really don’t care, because I don’t do anything to be deliberately offensive. But it’s my right to think that religion is disruptive, dangerous, and damaging, and that people who believe in god are misled. I’ve every right to think that. I don’t go out and say to somebody to their face, “You’re an idiot, you’re stupid, because you believe in god.” I don’t do any of that, but I will point out why I think it’s a crazy thing to think.

Your daughter, Persia, appeared on your last album and even toured with you. Will we find her lending her voice to Intruder as well?

Yeah, she’s on it far more, and so is my eldest daughter, Raven. They both sing on seven or eight songs. Persia co-wrote a song, but it’s mostly hers. It’s called “A Black Sun.” I think it’s one of the best things on the album. The idea of the earth speaking actually came from a poem that my youngest daughter, Echo, wrote. She wrote a poem called “Earth,” which was about the planet speaking to the other planets in the solar system and explaining to them why it was sad, and how horrible people were, and all the things that we were doing to it. She was only 11 at the time, so it was a very childlike interpretation of that idea, but it was brilliantly done. I just shamelessly stole it and turned it into an album. When you get the album artwork, the first thing you see on the inside of the gatefold is Echo’s poem.

“When the pandemic hit, it just perfectly fed into exactly what the album was talking about in a horrible, sort of tragic way. If the earth fought back, how would it do it?”

Do you still have a love/hate relationship with “Are Friends Electric?” and “Cars”? I know you’re sick of playing them live, but at the same time, they still bring money to the table, and introduce your music to a whole new generation.

For a long time, I had a real problem with them and there’s a very good reason for that. Those two songs became the symbols of me. If I would do a radio show, I’d turn up and they would play “Cars,” then I’d talk about the new song, which they wouldn’t play, and then I’d leave, and they’d play “Are Friends Electric?”—it was just frustrating. It began to feel like those two songs were like a weight around my ankles. I was aware of the interest and the money that they generated, but from a career point of view, I couldn’t move forward.

Then in 2009 I did a guest spot with Nine Inch Nails in London. Trent introduced me, he was talking about “Cars” and The Pleasure Principle era and how inspirational and innovative it all was to him. So I’m standing at the side of the stage in this massive arena listening to this from somebody that I respected enormously, saying all this stuff about songs that I’d been dismissing for the last 10 years. If somebody like that can see it as important and meaningful in the history of music, then surely I should, because I wrote it. So, I thought, “You wrote one of the most famous songs in the world. You should be proud of it.” But, having said all that, I’m still writing stuff and what I’m interested in is what I’m doing now, and especially what I’m going to be doing tomorrow. FL