Formed in Cologne, Germany in 1968 by a mix of Stockhausen students, improvisation jazz heads, and gypsy garage rockers with the intention of hard experimentation and “instant compositions,” Holger Czukay, Irmin Schmidt, Jaki Liebezeit, and Michael Karoli’s Can made genuinely jarring—and still unique sounding—studio albums. The hypnotic, rhythmic improvs of Tago Mago, the oblique Krautrock of Ege Bamyasi, the psychedelic maze of Monster Movie; each weave mesmeric spells, testing the waters of cut-and-paste sampling musique concrète and no wave funk. For all that free-everything, Can was never more at its freest, and least sentimental, than when they were playing live. For the most part, several of its studio albums were lengthy improvisations edited down to something more symmetrical. As for their actual hours-long live gigs, each was a circus of unpremeditated magic with only an occasional stop along their song catalog (and Can did have pop hits, such as “Spoon”).

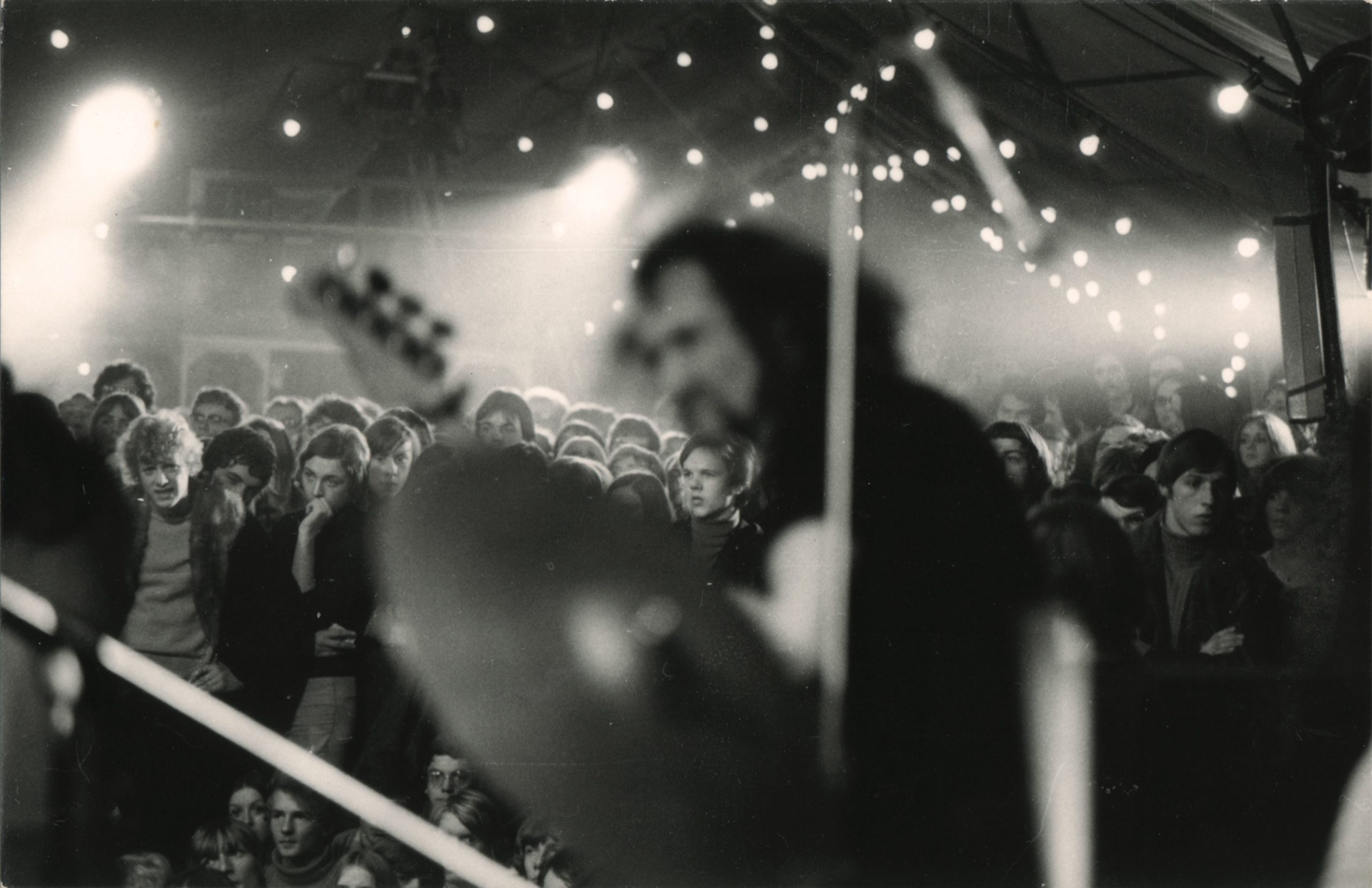

The last living founding member Irmin Schmidt, along with the beyond-Krautrock ensemble’s producer and engineer René Tinner, want the world to hear just how powerful and imaginative the Cologne-based band was in a concert setting. With that, the twosome—and the Spoon/Mute label—commence a Can Live Series, starting this month with Live in Stuttgart 1975, one long, explosive gig given “chapters” for a sense of setting, or a chance to breathe from the recording’s vividly imaginative whirlwind pace and on-their-toes interactivity.

Schmidt—a solo artist in his own right who studied with Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage, and György Ligeti—phoned from his home in Germany to kick around all things Can.

I want to start with the level of intuition, improvisation, and exactitude that was Can in a live setting. By the time you get to 1975, describe what sort of well-oiled machine Can was, and how the band maintained and provoked risk.

“Risk” is a very good word for what we did. The key, because we risked going on stage, always, without knowing what we were going to play. We came on stage and reacted to the atmosphere of the room, of the crowd, the ambience of the scene, and the lights. Of course, to each other. All spontaneously together. That, of course, is a risk, because…if you don’t have a set of songs, you invent.

You create something fresh. That clicks, and sometimes it doesn’t.

Yes, sometimes it does not click with the public. Or even our members. But, when it does, it’s totally different. We had a long time of being together, knowing each other, and playing together.

That is the legend of Can.

Yes, that we were each other’s intimates in a group setting. And that the public was part of the intuitive music and spontaneous creation when we all got together in a live setting.

“Listening to the tapes, it doesn’t bring up memories or any nostalgic feelings. It’s something we transferred into the air, and then it was gone. And now it has its own life. Once it’s delivered into the world, I have nothing to do with it, even if I had everything to do with it.”

What do you remember about that 1975 Stuttgart show? Did you relive it when you heard the live tapes to mix this new album?

No, I don’ t believe that I relived it. Listening to the tapes—it’s a magnificently good concert—it doesn’t bring up memories or any nostalgic feelings. There aren’t any deep emotions. It’s something we transferred into the air, and then it was gone. And now it has its own life. Once it’s delivered into the world, I have nothing to do with it, even if I had everything to do with it.

It becomes part of the universe. You could be listening to anything.

It’s as if I’m listening to somebody else’s music. Now, if I’d heard something bad, only then would I recognize it, and say it was us. And I should say, too, that there are concerts that I do remember, but only because I met extraordinary people, or a guitar got stolen, or something strange happened. Never the music.

I can recall one show meeting these Hell’s Angels types. Bike freaks. They were wonderful. I can remember a show in Birmingham, England where I was running a very high fever and had to take speed to get through the concert, when all of a sudden I fainted over the organ. I laid there for a bit. Finally, I woke up and the whole audience was screaming and cheering. They thought my fainting was part of the show. There was another concert in Scotland where a handful of viking types showed up, and one of them came on stage, embraced me, and said this was the most wonderful experience of his life. He broke my ribs. These events you remember. The music itself, not so much.

photo courtesy of Spoon Records

I know that you spent time as a conductor before Can came together. How did that experience with the Vienna Symphony affect the democracy of Can?

There’s a certain clarity in the role of a conductor. The interpretation of the symphony, or what have you, is primarily the conductor’s interpretation. It’s not the first oboist, etc. There may have been certain qualities that I learned as a conductor that I brought to make music with others. You hold things together when there are crises as a conductor.

You studied with Cage and Stockhausen, composers not known for their reverence to form or tradition. Do you feel as if that gave your permission to be irreverent even to them? And how do you feel as if those studies inspired your work as part of Can?

Being a pianist, and having started that act relatively late in life for a classical pianist, you have to work at it for hours upon hours a day. One side of my musical education was highly disciplined. When you work with an orchestra, you can’t bullshit. And you want a classical orchestra to be disciplined. These composers that I learned from, they were all different. From Ligeti I learned about the incredible richness of coloring, the many colors of each instrument. Stockhausen’s music was the first music I heard that was made purely electronically. I learned about form from him…he was very dogmatic. I didn’t treat it dogmatically, but it was interesting nonetheless.

“We were not friends—it was an abstraction. We decided to get together and find out what would happen. There weren’t assigned roles. What was there was that everyone brought all of themselves, their history, the tradition, their non-tradition, into one concept, one organism. And from time to time, we succeeded.”

Doing all these studies, wanting to be a composer, having an idea to create a new vision of contemporary music—the change from classical into, say, Cage—I didn’t feel as if I was throwing away one area of my learning so as to achieve success in another. It was logical. The experience of being with Cage, period, was liberating. It changed my approach as a musician to all music. Cage made the horizon very wide. From there, I brought all of my experience with these masters into Can. And I made my own experience.

Outside of the actual instrumentation, what can you tell me about who served what roles in Can, be they assigned or self-designated? No single member seemed like a leader, even when you involved vocalists.

When I founded and got these people together—well, Holger brought Michael with him when he joined—my idea was a totally abstract thing, that contemporary music I was involved in such as Fluxus, Stockhausen, and Cage wasn’t just rooted in classical, but could also be jazz, which itself came from blues, which itself came from traditional African music. I wanted to make music with people who came from different traditions than my own, and different from each other.

Jaki was a jazz musician who had never played rock. He started at age 13 in Dixieland bands, played all forms of jazz, and wound up in the free jazz scene. Holger was like me, rooted in contemporary music and some jazz, but he was very experimental. Michael was a pure rock guitarist. We were not friends—it was an abstraction. We decided to get together and find out what would happen. We didn’t plan to be a rock group. We didn’t plan to be any kind of group. Just being a group was the aim. So, no, there weren’t assigned roles. What was there was that everyone brought all of themselves, their history, the tradition, their non-tradition, into one concept, one organism. And from time to time, we succeeded.

It stuck with me when you said that Can didn’t start out as friends. I can tell, too, that you aren’t some rank sentimentalist. I’m curious, then, as to what about your Can-mates lingers? What do you miss about the interaction among the four of Can’s members?

I miss Michael because, even though we didn’t know each other at the start of Can, we did become very good friends. He was among my closest friends I ever had in my life. I made music with Michael until he died—just not as Can. Jaki and I were planning an album together, a duo, up until the days before he passed away. I don’t miss Can. I wouldn’t want to keep doing the same thing with the same people over and over. I don’t miss them as musicians. I don’t miss our experiences. But yes, we the members of Can developed into great friends, and I do miss that. Can, as an experience, marked me more than anything else I have done. Jaki always called what we did “instant composing.” Stockhausen would have called it “intuitive music.” It’s a cycle, whatever you call it. Jaki, Holger, and Michael: I learned as much from them as any of my mentors. FL