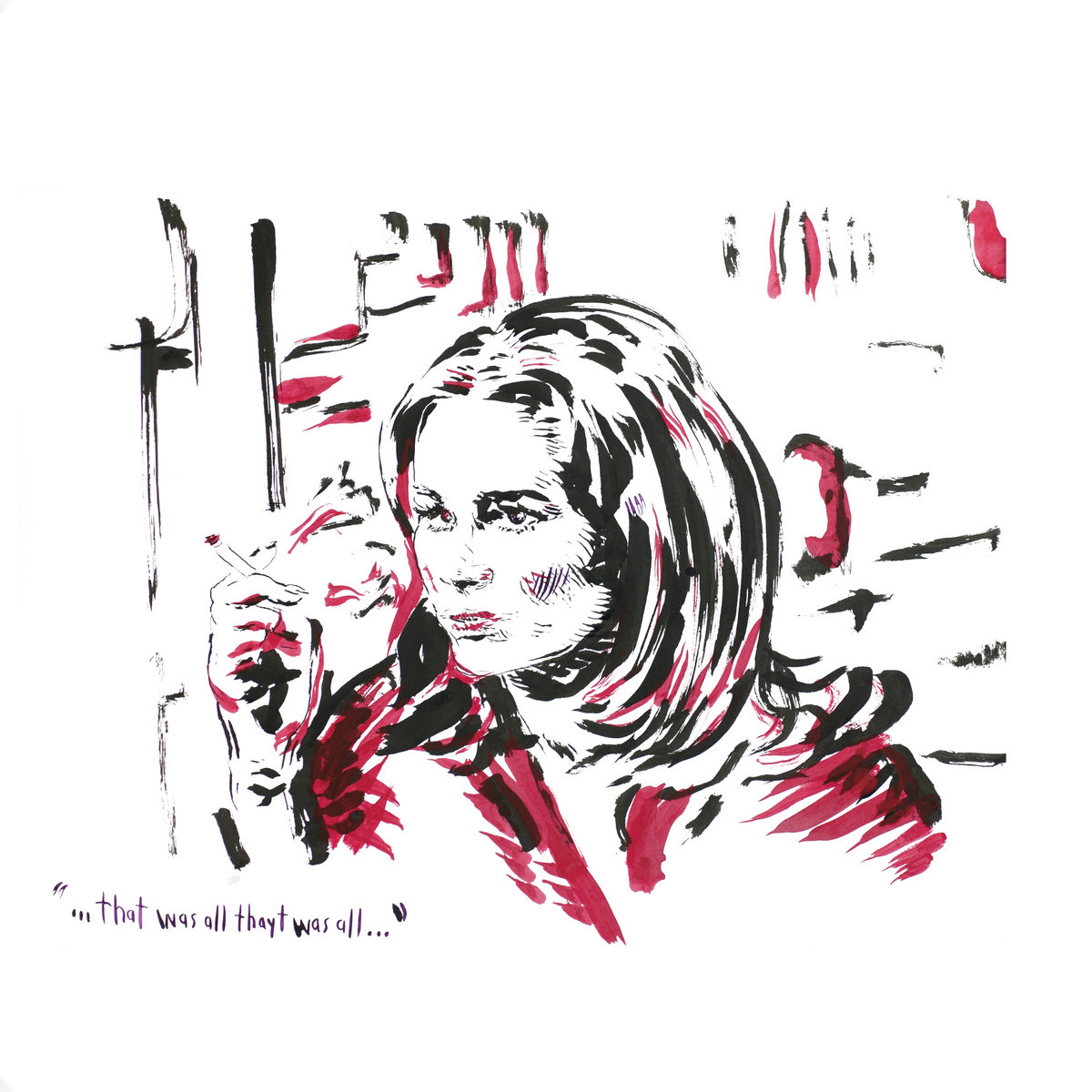

Karen Black

Karen Black

Dreaming of You (1971-1976)

ANTHOLOGY

7/10

Karen Black has been gone for the better part of a decade now, but her spirit is very much present on this posthumous debut album. Though known primarily as an actress—her first major role was in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1966 movie You’re a Big Boy Now, and she won two Golden Globes for Best Supporting Actress during her career—Black was also a keen songwriter. While it wasn’t a career path she followed, she would write and record songs frequently.

Dreaming of You (1971-1976) gathers 15 of her recordings from that period, plus two more recorded later with Cass McCombs for an unfinished solo album they’d been working on for her. The pair had met in 2008 through a mutual friend, and became not just good friends but also collaborators—Black appears on McCombs’ “Dreams-Come-True-Girl” on 2009’s Catacombs, and again on “Brighter!” from his 2013 record, Big Wheel and Others. After her death that same year, McCombs worked with Black’s husband Stephen Eckelberry to bring her many recordings to life with restoration engineer Tardon Feathered.

The result is an album of ghosts and haunted hearts, Black’s chilling, soothing vocals shimmering with a raw, real pain. Simultaneously old-fashioned and contemporary, “Sunshine of Our Days” and “It All Turned Out the Way I Planned It” are gentle, lilting folk songs that could be mistaken for Lucy Dacus or Julien Baker compositions, while the melancholy “You’re Not in My Plans” and the almost-Portishead-esque “Dreamland” demonstrate the more eerie side of her songwriting. Then there’s the jazzy heartbreak of the title track and the solemn sadness of “That’s Me,” the triumphant but deflated piano ballad “Thank God You’re Mine” and the sparse, hymnal “Passing Through,” which truly does sound like a soul leaving its body.

As a final posthumous postscript, a bonus 7-inch features the two songs made with Cass McCombs. The A-side, “I Wish I Knew the Man I Thought You Were” is a stirring anthem that depicts a real-life relationship Black had as a student with a professor in the ’60s, and is riddled with a harrowing, inappropriate minor chord majesty and chilling earnestness. The B-side, “Royal Jelly,” is an experimental layering of Black’s vocals that ends in simulated shrieks of orgasmic delight. It’s an odd finale that’s out of sorts with what preceded it, but which still can’t detract from this collection of songs by someone who should have been regarded as a classic artist.