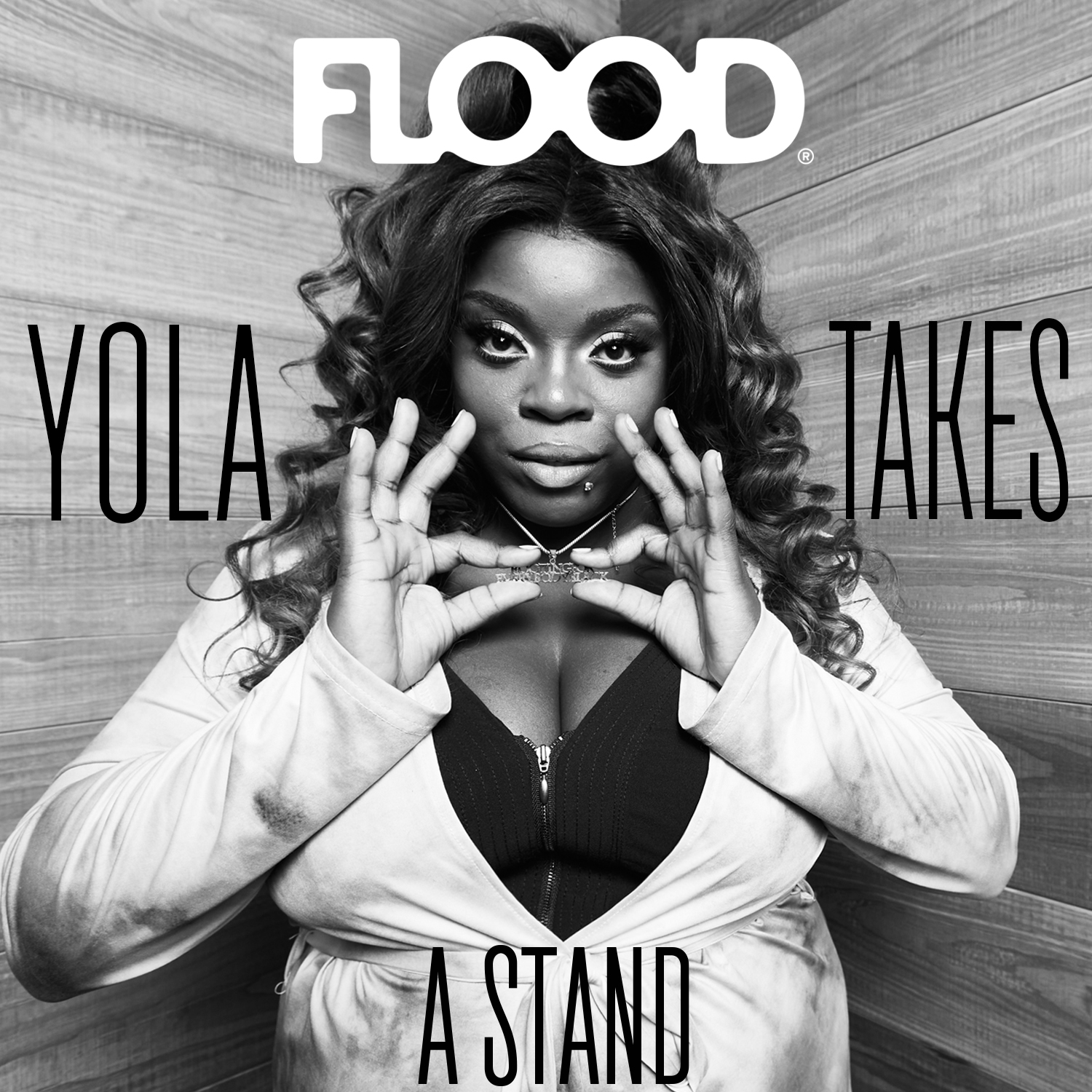

While the COVID-19 pandemic upended countless lives, the advent of the virus and ensuing lockdown had a profound, metamorphic impact on Yola. As the pandemic took hold, the Bristol, England-bred singer-songwriter made the decision to relocate to Nashville—a decision that, she explains, wasn’t made entirely by choice, and a move that would inadvertently shape her new album Stand for Myself.

It would be easy to say that Stand for Myself picks up where Yola’s breakout 2019 LP Walk Through Fire left off, but to do so would ignore the tremendous accomplishments—both professional and personal—Yola racked up in between the creation of the two albums, all of which shaped and inspired the songs on Stand for Myself. She was nominated for four Grammy Awards and two Americana Music Honors & Awards distinctions, wowed audiences with a viral performance at 2019’s Newport Folk Festival, and joined The Highwomen on their acclaimed debut album, among many other accolades. She also found greater footing in an industry that notoriously stifles Black and female creators

The most obvious difference between Walk Through Fire and Stand for Myself, both of which were produced by Dan Auerbach, is the set of influences Yola pulled from, which present themselves in a slicker, funkier, and poppier fashion than those in the rootsy, soul-country style of its predecessor. Opener “Barely Alive,” for example, glistens with percussive Wurlitzer and a soaring chorus reminiscent of late-’60s and early-’70s soul. “Great Divide” builds a cinematic ballad atop a simple piano arpeggio, with Yola’s agile vocal ranging from a near whisper to a full-on belt throughout.

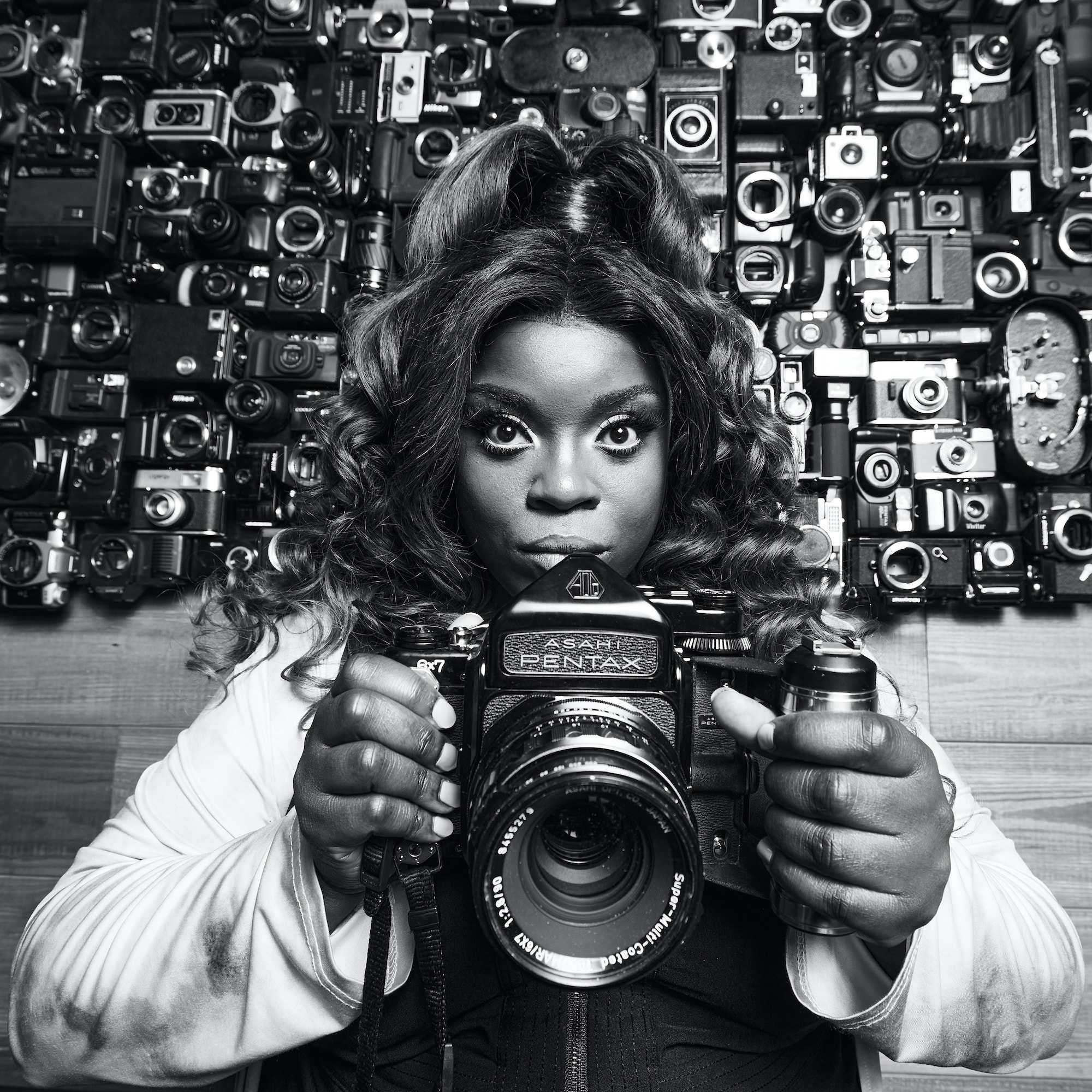

“The album sounds more like the myriad things that a British child might have grown up listening to if they were growing up in the ’90s or the ’00s, and the things they might have been exposed to from their parents’ generation,” Yola shares during our interview in Nashville back in May. “So it’s very exposing of a thirtysomething British lady, specifically maybe even a Black one, at least from the lens of the lyrics, but aesthetically it’s just where I’m from and the age I am.”

Much of her reconnection with her musical roots came during lockdown, when she was forced into solitude and had the time and space to reflect upon what kind of music moved her and what kind of music she wanted to make. That was also when she decided that if she was making music in Nashville, she may as well live there, too.

“It’s going to be different for me than a lot of people you talk to because I’m not from here,” she says of her pandemic experience. “I moved just before the ‘wall’ came down. Or, I shouldn’t say I moved,” she laughs. “I was here, got trapped, and then decided to move. A lot has changed. ‘Transformative’ would be the way to describe it, in short, at least. I made a decision to be here and to, I suppose, make sure that my creative process was born out of here.”

Though she didn’t make her residence official until March of 2020, Yola was no stranger to the city of Nashville prior to her move, having released her breakthrough debut album via Auerbach’s Nashville-based record label Easy Eye Sound in 2019. Even before the release of that album, Yola was a Nashville favorite, having made an impression upon audiences of industry veterans and casual listeners alike during performances at past AmericanaFest events and with the music on her 2016 EP Orphan Offering.

She subsequently developed a passionate network of fans, colleagues, and collaborators, a talented and kind bunch who would prove invaluable when the time came to create Stand for Myself. That wasn’t a luxury she had while making Walk Through Fire, as, at that time, the vast majority of her creative network was still overseas in England.

“When you’re an artist, you build a whole network of people who allow you to get from point A to point B,” she explains. “Obviously, I’m signed here [in Nashville], so I needed to be here. So that was a really big part of the decision. And I was fortunate in that just before lockdown I’d done my first headlining tour for two months. I’d also done [2020] Grammy week, because of the four nominations I’d received.”

To that end, Yola’s official relocation to Nashville was a big win for a city who already adored her singular sound, her potent songwriting, and, of course, her powerhouse voice. It was also an unexpected gift for Yola herself, who—after years of relentless touring, recording, and press—was in dire need of a good break.

“Great writers find their way emotionally, especially lyric writers—you know, people who aren’t just trying to impose their life narrative onto your narrative. They’re really trying to find the true things to say in that moment. That became a really big part of what I was trying to do, always finding collaborators who really get what we’re talking about.”

“I was so exhausted that I was quite grateful for some time off,” she says. “I was like, ‘That was great and everything, I’m not going to sniff at four Grammy nominations for love nor money, but I’m rinsed.’ I thrive in nothingness. It’s my favorite bit. It shows what people might not expect from me, which is the introverted side of me. Because I’m relatively extra, people might go, ‘Oh, that’s all there is.’ But we’re all quite complicated. In my sense, I have a healthy dose of introversion as well, which is fed wonderfully by this nothingness. And I wasn’t getting any of that.”

That forced time alone did prove to be restorative, but more than that it gave Yola the chance to take a good, hard look at the fact that what she needed to make was music that was truly in line with who she was as an artist and as a Black woman. That included taking stock of how, and with whom, she made Walk Through Fire, and what she would retain from that process on Stand for Myself.

“Sometimes the thing you want to do doesn’t exist,” she says. “And so, I just had to figure things out. The result of figuring things out was the ‘get to know you’ album, Walk Through Fire, the grand collaboration. To be blunt, I inevitably was responsible for more of the lyrics on Stand for Myself because of isolation. So it forced maybe a little bit less collaboration, as a result. Though not an absence—we still have many co-writers.

“But being isolated for as much time as we were,” she continues, “it forced the hand for me to write in a way that maybe I didn’t write as much of on the first record. I was the song-starter the majority of the time, going, ‘This is my seed, I’ve got a verse and a chorus.’ It was so much more of coming to the table with something that’s in a decent state, and then [to a co-writer] going, ‘Cool, can you get this over the line for me?’”

“I remember Black people talking to each other, going like, ‘You alright? Yeah. You getting a million calls from white people that don’t talk to you? Yeah. Is this super fricking tiring? Yeah.’ So that really shut me down.”

Yola tapped a stacked roster of co-writers for Stand for Myself, including Joy Oladokun (“Barely Alive”), Aaron Lee Tasjan (“Diamond Studded Shoes”), Ruby Amanfu (“Be My Friend”), Paul Overstreet (“The Great Divide”), Liz Rose (“Break the Bough”), and Natalie Hemby (“Dancing Away in Tears,” “Diamond Studded Shoes,” “If I Had to Do It All Again,” “Now You’re Here,” “Stand for Myself”), the last of whom she had earlier collaborated on Hemby’s Highwomen project. Auerbach also has several co-writing credits on the album.

“She’s very good at her job,” Yola says of Hemby. “Great writers find their way emotionally, especially lyric writers—you know, people who aren’t just trying to impose their life narrative onto your narrative. They’re really trying to find the true things to say in that moment. That became a really big part of what I was trying to do, always finding collaborators who really get what we’re talking about.”

Oladokun, though only credited on one track, was also an important collaborator for Yola, particularly through the conversations they had throughout the COVID-19 lockdown. Those conversations would eventually lead to opener “Barely Alive” and would also find their way thematically into several other of the album’s tracks.

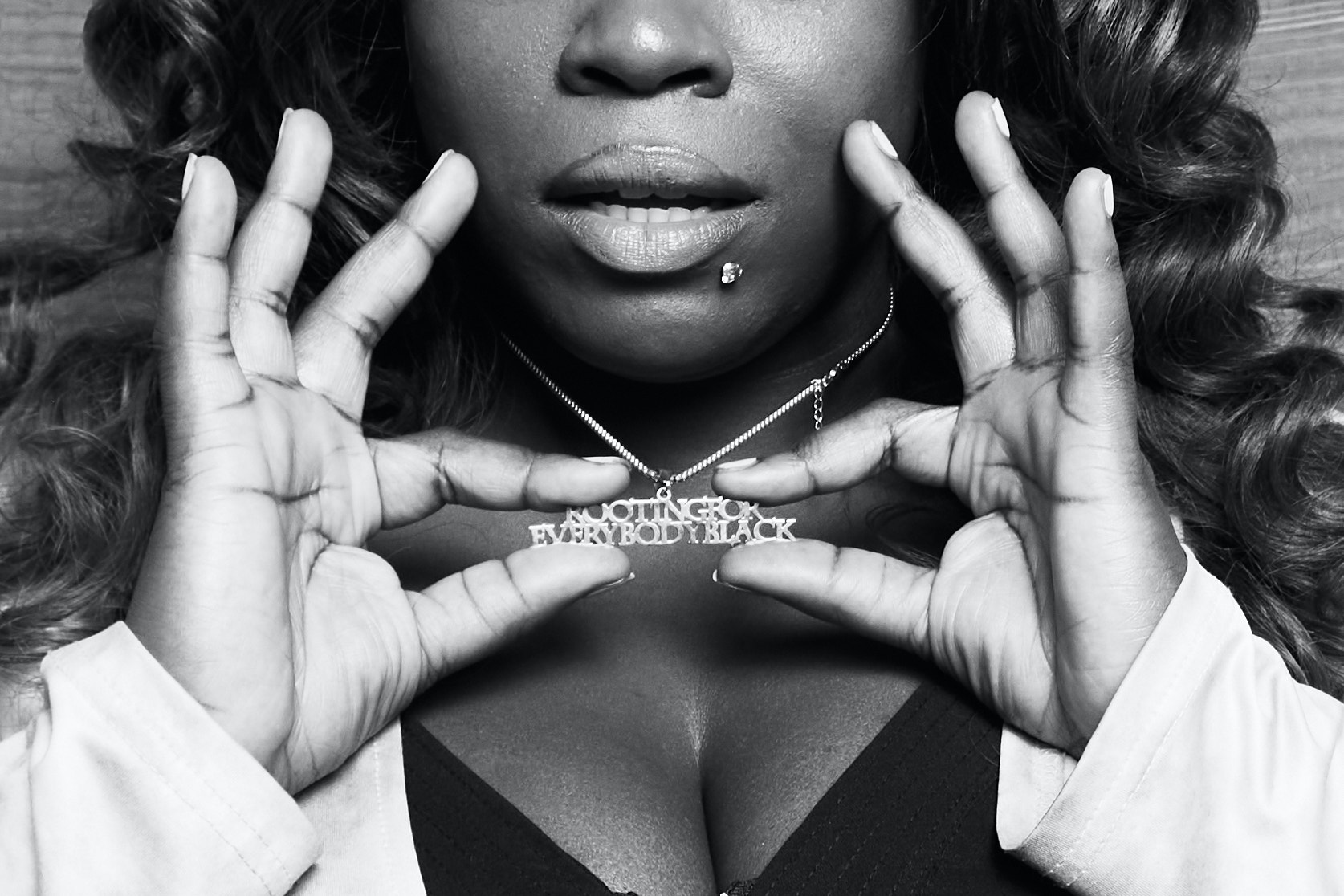

“We were talking about what it’s like being a token Black person in a space playing guitar, writing songs,” she says of her conversations with Oladakun. “And being dark-skinned as well, and not being light-skinned and having the privilege in that, and all the ways that affected our lives and created ways we’ve felt like we had to minimize ourselves.”

Like “Barely Alive,” which grapples with truly living rather than merely surviving, fellow album standout “Break the Bough” ventures into deeply personal territory, as Yola wrote the song following her mother’s funeral in 2013. The track’s music wouldn’t sound out of place in a ’70s dance club or on a show like Soul Train, but its message is steeped in grief, albeit a hopeful kind: “Silently free the soul, oh let it be released,” she sings. “Let it spread and find a home, maybe then you will find peace.”

Yola introduced the Stand for Myself era with “Diamond Studded Shoes,” a seemingly playful, soulful romp that tackles wealth inequality, with its title pulled from the pointed lyric, “We aren’t the rich ones, some of us will barely get by / They buy diamond studded shoes with our taxes, anything to keep us divided.” As is the case with songs like “Break the Bough,” Yola wanted to create tension between the sound of “Diamond Studded Shoes,” which recalls the glitz and twang of Honky Château–era Elton John, as well as the social commentary of its lyrics.

While the pandemic had more of a passive impact on Yola’s songwriting, the worldwide protests against police brutality and racial inequality that marked the summer of 2020 had a much more active one, in that the emotional impact of the events temporarily stalled the creative flow she had found in the solitude of quarantine.

“I got to a point where I’m like, ‘I’m gonna have to put these songs out. They’re just getting truer every time I think about them. I really felt like I wanted to put these songs out when they were at their truest.”

“I couldn’t write,” she says of the time following the murder of George Floyd. “Because it was harrowing! I thought, ‘I wonder if that will actually show in my voice notes.’ It did. I couldn’t do anything. It was horrible. I remember Black people talking to each other, going like, ‘You alright? Yeah. You getting a million calls from white people that don’t talk to you? Yeah. Is this super fricking tiring? Yeah.’ So that really shut me down.”

She may have felt “shut down,” but during that month-long break from songwriting Yola was able to take some of the grief and trauma she was experiencing and processed it into songs. She sees this phenomenon in her songwriting as parallel to a greater societal reckoning with and understanding of the perilous consequences of racism and the systems that uphold white supremacy.

“We didn’t have an opportunity to do anything other than stare directly down the barrel of the gun,” she says of the summer of 2020. “Part of the militarization of police and all these kinds of things is getting people mentally ready to [pull the trigger]. Conditioning is a big part of it. Being still enough to watch the result of that, it’s just quite harrowing to actually witness.”

None of these issues are new, so it makes sense that some of Stand for Myself’s more pointed, socially conscious tracks were written prior to 2020. “Diamond Studded Shoes,” for example, which Yola notes one would expect to have come out of the 2020 U.S. presidential election, was actually written in 2017; income inequality was as alive then as it is now, and the song holds just as true.

“I got to a point where I’m like, ‘I’m gonna have to put these songs out. They’re just getting truer every time I think about them,’” she says. “I really felt like I wanted to put these songs out when they were at their truest.”

Now that live music is back and finding its footing, Yola is excited to get out on the road to share these new songs with fans. The downtime forced by 2020 may have been a wellspring of inspiration, but her inner extrovert needs tending, too. And with Stand for Myself, she’ll have a new collection of songs authentic to her experience to buoy her until that next round of inspiration inevitably strikes. FL