Midwife

Midwife

Luminol

THE FLENSER

7/10

When I think of Madeline Johnston’s work as Midwife, I remember Alfred Tennyson’s poem “The Lotos-Eaters,” where a group of sailors fall into a fantastical trip after eating the titular flower and forget their purpose of returning home. Tennyson writes, “In the afternoon they came unto a land / In which it seemed always afternoon.” In a similar loop, Johnston’s songs share a mental landscape; they deliver a moment of indulgence suspended in a malleable moment, like watching a kickflip in slow motion on repeat.

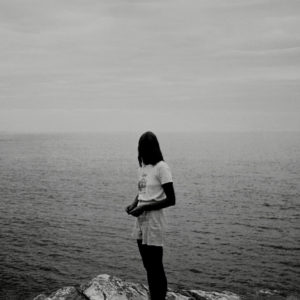

On Johnston’s third album Luminol, the New-Mexico-via-Denver artist explores a year of isolation through laconic lyrical composition and repetitive loops. Self-coined as “heaven metal,” the album feels like a mental tête-à-tête among someone who’s falling asleep at a rave. Such a juxtaposition is quite rare—hypnotic pop that thrives in the vein of Grouper and holds moments both sizzling and cacophonous. Johnston fully created the album in the pandemic, unwrapping a new genre exploring what it means to be lonely and loud simultaneously, and executes an expansiveness within a world crumbling around us.

Johnston starts the album with “God Is a Cop,” a track etched with echoing vocals and reverberating piano, paving the sound bath experience the rest of Luminol stands in. In another track, “2020,” she sings, “It feels like / Heaven’s so far away,” stretching, perhaps, a terror of never knowing what’s next in a year of unpredictability. The album ends with “Christina’s World,” an eerie piano ballad driven by nothing but the crack of a whispering snare in the backdrop. Johnston sings “Show me the way” repeatedly, each time with inching intensity as the effects wrap around vocals, piano, and snare. Before the grand finish, there are about eight seconds of silence to sit in.

A few weeks ago, I watched ambient artist Mary Lattimore perform in a cemetery alongside a sequence of dancers. In a way, Lattimore and Johnston share an affinity when it comes to musical presence. Each reverberation was cupped in a communal offering where everyone’s listening together; the chirping birds, rustling leaves, and a neighbor kicking dirt after switching their sitting position all welcomed themselves into the orchestration. And like Tennyson, Johnston makes music that sketches moments we sometimes don’t commemorate with our pens or count on our fingers. They’re messy sounds that rely on memory for recall, like crossing minute realities into your dreams. Such a type of satisfying confusion is hard to understand, perhaps because it’s overwhelmingly personal.