George Harrison

George Harrison

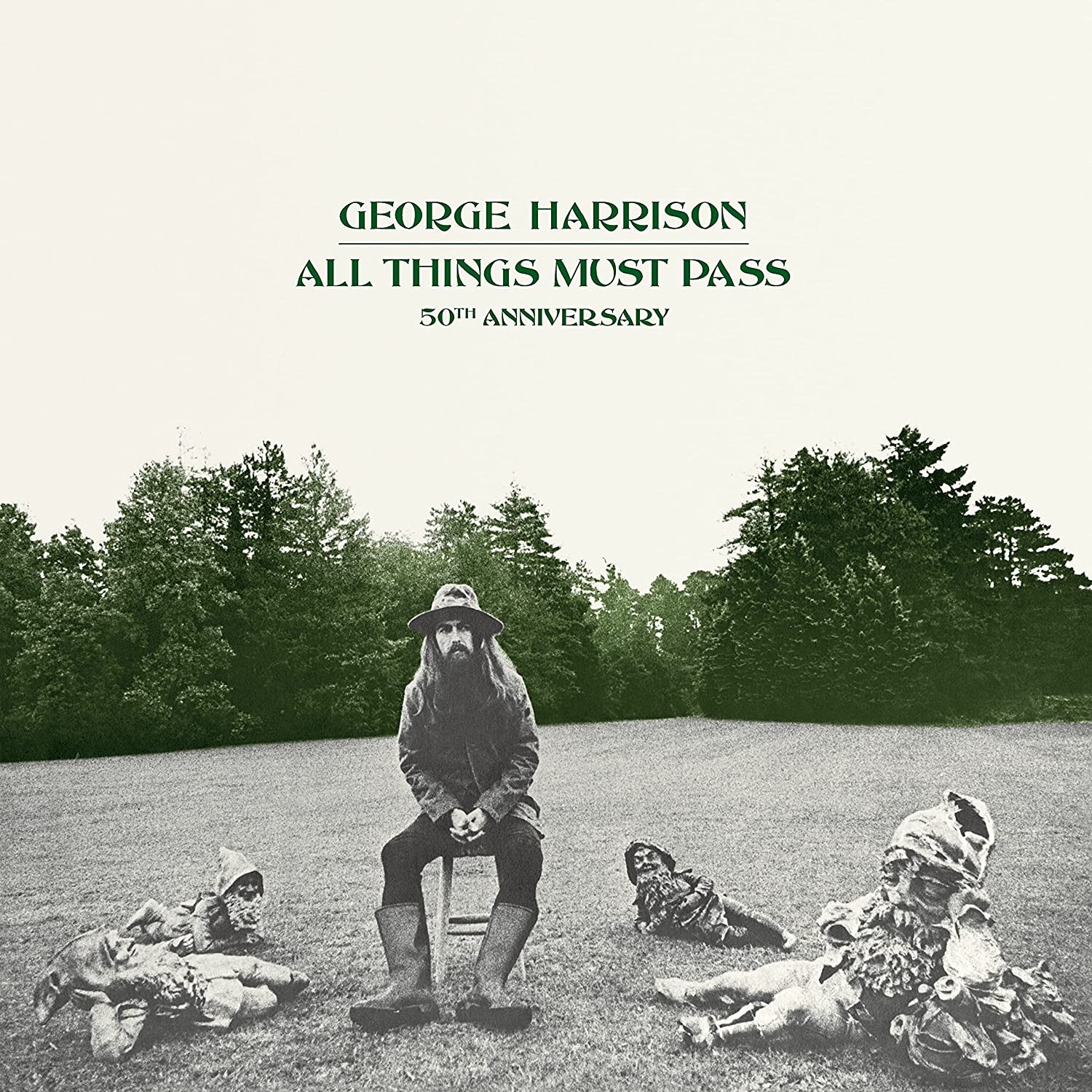

All Things Must Pass Super Deluxe Edition

CAPITOL/UME

9/10

George Harrison never got a real chance to fully express himself as a dramatic, crafty songwriter or an emotive singer in the Fab Four, so the so-called “Quiet Beatle” went on a recording spree just as his quartet was dissolving—sessions resulting in the immense-sounding, deeply personal, three-album glut that was All Things Must Pass. Co-produced by Harrison and Phil Spector, the 23-track (including its improvisational Apple Jam tracks) LP not only showed off the guitarist and singer in a production and band leadership role, but also as both a conduit for the Holy Spirits that guided his hand and as a keen middleman between the pop past of the Beatles (Harrison’s All Things songs were nothing if not irresistibly catchy) and where the rock idiom was moving (post-psychedelia, the Americana of The Band) at the end of 1970. All this, and from its improvisations and its often mesmeric, raga-like feel, through to its epic proportions, All Things was the sound of freedom, of release.

Why not celebrate Harrison’s epic vision of failed relationships—personal and professional—and spiritual enlightenment, then, with a doubly expansive, never-before-heard hi-res stereo sound, 42 previously unreleased demos and outtakes, and—if you’re in a spending mood—a wooden bookmark made from a felled oak tree in Harrison’s Friar Park home, replica figurines of 1970-era George and the gnomes featured on the album cover, an illustration from Klaus Voormann, and Rudraksha prayer beads?

Harrison’s original All Things Must Pass was bright in tone and luster with his vocals high in its mix (unlike all of the Lennon solo work co-produced with Spector) for an effect I’d call a Wonderwall of Sound in dedication to both producers’ visions. This reissue, then, adds an oomph to the bottom end that’s crucial to its rhythm arrangements, its brass, and the tremor of Harrison’s usually treble-heavy guitar work, acoustic and electric. “Going Down to Golders Green (Take 1),” for instance, has the folksy warmth of a campfire. So, too, does the country-fried “Woman Don’t You Cry for Me,” “If Not For You (Take 2),” and the all-acoustic, deeply bluesy “Sour Milk Sea,” a strummed holy rocker that flickers and juts like a fire’s flames.

The electric noodlings of the Apple Jam tracks sound hot-wired and intentional without losing their loose improvisational vibe. The stripped-to-the-core versions of the spiritualized title track and the rousing “What Is Life” are somehow more glorious and grand here in their skeletal state than in their original album’s opulent vestments. “Isn’t It a Pity (Take 27)”—one of several different studio demos and outtakes of the hymn, and certainly a most emotional vocal workout for Harrison—has more density in its sound no matter how the arrangement and instrumentation changes. It’s as if each take was discussed with Harrison himself (kudos to son Dhani Harrison for being on top of every aspect of this project).

As for the bite of the Apple, The Beatles and life in a celebrity bubble, songs such as Harrison’s Dylan co-write “Nowhere to Go” show off the disgusted side of the Quiet One, a nattering vibe far beyond the pissiness of, say, “Taxman.” And while “Get Back” is a direct slap (albeit a good-humored one) at the Fab Four, there’s a sense of longing for the past—the realization that some goodbyes are permanent—on “I Don’t Want to Do It.” Again co-written with Bob Dylan, Harrison mournfully sings “I don’t want to say goodbye” in a manner that questions his move for a solo career. But regret is not an option, and the effervescent takes on rarities such as the gently soulful romancer “Beautiful Girl,” the uplifting religious-acoustic demo “Cosmic Empire,” and the meditative drone-mantra “Om Hare Om (Kopala Krishna)” in their newly revitalized form prove how right George Harrison was to move on, and to never look back.