This article appears in FLOOD 12: The Los Angeles Issue. You can purchase this special 232-page print edition celebrating the people, places, music and art of LA here.

“It’s always been a dream of mine to have a label,” Phoebe Bridgers told Billboard in October 2020 when she announced the formation of Saddest Factory Records, “because I’m also such a music fan.”

Indeed, Bridgers’ dream goes back to well before her own first official release in 2015. “Before I even signed my record deal,” she recalls, “I was like, ‘I should just self-release.’” Her manager, though, advised her against doing so. “[He explained that] I’d have to manage every aspect of the release, work with distributors, and decide where every single marketing dollar went.” So when it came time to choose a label for her 2017 debut LP Stranger in the Alps, she went with Dead Oceans, home to such luminaries as Mitski, Toro Y Moi, and Japanese Breakfast.

Photo by Michael Muller. Image design by Gene Bresler at Catch Light Digital. Cobver design by Jerome Curchod.

Phoebe Bridgers makeup: Jenna Nelson (using Smashbox Cosmetics)

Phoebe Bridgers hair: Lauren Palmer-Smith

MUNA hair/makeup: Caitlin Wronski

Phoebe Bridgers makeup: Jenna Nelson (using Smashbox Cosmetics) Phoebe Bridgers hair: Lauren Palmer-Smith MUNA hair/makeup: Caitlin Wronski

It was a perfect fit. In fact, Bridgers vibed so well with Dead Oceans during the Stranger in the Alps promotional campaign that when she and Bright Eyes frontman Conor Oberst were looking for a home for 2019’s Better Oblivion Community Center—their collaborative duo’s self-titled debut album—the label was the obvious choice. Oberst, who had spent two decades on Saddle Creek, was likewise so impressed by how Dead Oceans worked BOCC that he brought Bright Eyes to the label in 2020.

“What’s my commission?” Bridgers joked to Dead Oceans co-founder Chris Swanson after the Bright Eyes signing. “And then it became real,” Bridgers recalls. “[He] was like, ‘Let’s do it. You can totally have a label.’” Thus, the cheekily named Saddest Factory Records was born, joining the Dead Oceans, Jagjaguwar and Secretly Canadian labels as part of the Secretly Group.

Giving Bridgers her own label was no idle whim on Swanson’s part. The success of Punisher—Bridgers’ sophomore LP, which ranked at the top of almost every prominent culture publication’s “Best Albums of 2020” list—had led to her performing on Saturday Night Live and singing on Taylor Swift’s re-recorded version of Red, giving her exactly the visibility she’d long sought for promoting the music of her tight-knit but gradually expanding musical community in LA and elsewhere. With Saddest Factory Records, Bridgers gained a vehicle for making good on that elevated platform: a musical community with LA roots disguised as a traditional music business, one reaching the whole country—and world—on the back of its leader’s ever-cresting exposure.

Haley Dahl (Sloppy Jane) inadvertently supplied the label’s name with a 2019 tweet that read “saddest factory guaranteed.”

Haley Dahl, Sloppy Jane

“LA is my hometown, so a lot of the bands are from here,” Bridgers says of her label’s roster. Haley Dahl, frontperson of avant-rock outfit and Saddest Factory signee Sloppy Jane, was on the same childhood soccer team as Bridgers. “We both went to these weird hippie schools down the street from each other,” Dahl says. She and Bridgers began playing music together in high school: “I started Sloppy Jane, and Phoebe was already performing as herself. She played bass with us during high school and a little bit after, and we've remained friends and mutual appreciators.”

After returning to her birthplace of New York City in 2017, Dahl created the current incarnation of Sloppy Jane: a bleak, theatrical chamber-pop group with nearly a dozen members. Upon signing with Saddest Factory, Dahl issued a statement that paid tribute to Bridgers’ passion for her band. “When I was moving to New York I talked about how I wanted to make the band bigger and incorporate chamber instruments, and a lot of people didn’t get what I meant,” Dahl’s statement read, “but Phoebe said, ‘Go get your orchestra.’” (Dahl also inadvertently supplied the label’s name with a 2019 tweet that read “saddest factory guaranteed.”)

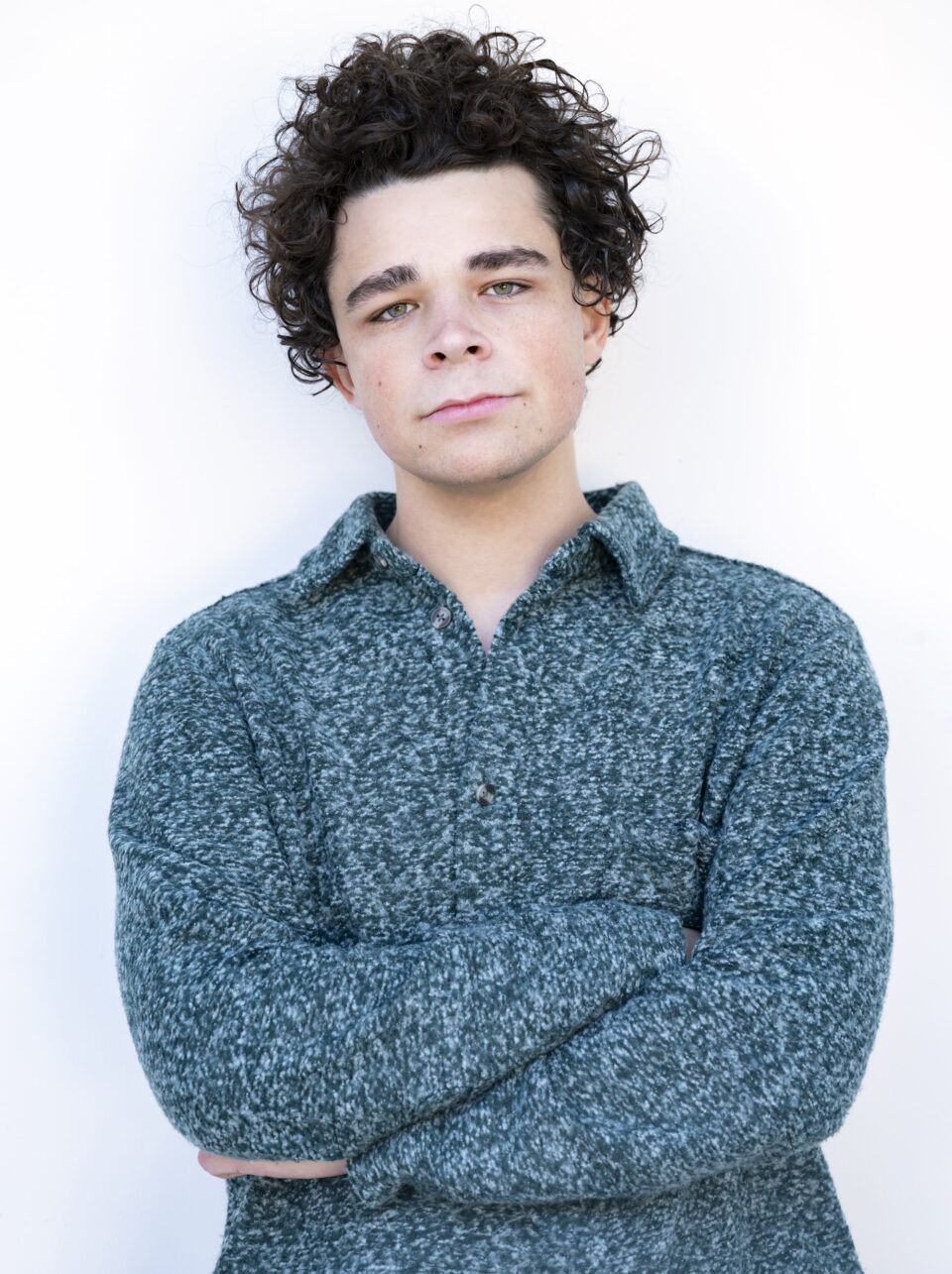

Charlie Hickey

“[Phoebe] was in high school when I was in middle school and she was already writing songs that were better than anybody else’s.”

— Charlie Hickey

Similarly, folk-adjacent musician and label signee Charlie Hickey met Phoebe while they were both growing up in Pasadena. “She was in high school when I was in middle school,” Hickey recalls, “and she was already writing songs that were better than anybody else’s. I heard her play when I was 13, and I became obsessed with her music. I was like, ‘This is some of the best music I've ever heard, and maybe this is the kind of music I want to make… This feels like my path.’ Then, we became friends [after] I covered her on YouTube.”

That 2013 cover of Bridgers’ “Radar” is still up on YouTube, but all the comments on it are from within the past year, a clear reflection of Bridgers’ impact. Long before Hickey and Bridgers connected, his creativity was apparent: Both his parents are singer-songwriters, so naturally he was already writing songs in elementary school and performing them in middle school. In a way, he was as prodigious as Bridgers herself. It seems fated, then, that their two worlds collided.

Speaking with longtime Bridgers friends like Hickey and Dahl, as well as newer members of Bridgers’ circle, it becomes clear that her genuine fandom ties all of Saddest Factory’s signings together. A few years back, her drummer, occasional co-writer, and best friend Marshall Vore—who’s also a sought-after producer in his own right—sent Bridgers an EP by the musician Claud Mintz, who records under the mononym Claud, and Bridgers loved it so much that she asked Claud to lunch. “Then, we started hanging out and talking about the label,” says Claud. “It was immediately this conversation of, ‘Hey, I love your music and I'm starting a label.’”

Saddest Factory Records isn’t Claud’s first label rodeo. In 2018, they released their Toast EP on Terrible Records, co-founded by Grizzly Bear’s Chris Taylor. They then branched out the EP’s melancholic and midtempo sounds into upbeat, synthy terrain on Sideline Star—the one Vore showed Bridgers. But it’s Claud’s Saddest Factory Records debut, Super Monster, where their formative admiration for big-name pop stars becomes more evident—their preteen love of Justin Bieber and the Jonas Brothers bleeds into the album’s sense of humor and fun.

Claud isn’t the only Saddest Factory artist with whom Bridgers first connected through Vore: Naomi McPherson of electronic pop trio MUNA, whom Bridgers says she listened to often in her early twenties, says the group also met Bridgers through Vore. “We were playing out at the Bootleg,” they recall, “and that was the first time we'd met in person, and we just chopped it up a little bit.” Later, the group heard that when Bridgers saw them live, her reaction was along the lines of, “This would be a band I would love to sign if they weren’t already signed.” “And then, as it happened,” McPherson says, “we were no longer signed. So it just sort of worked out.”

The trio, rounded out by Katie Gavin and Josette Maskin, was a huge get for Bridgers. Whereas the rest of the Saddest Factory Records roster could be fairly described as newer artists, MUNA—whose members first met at USC—has had two albums in a row peak at #7 on the Billboard Heatseekers chart. In 2016, their single “Winterbreak” (released, along with their first two albums and an EP, by major label RCA) also made Billboard’s Hot Rock & Alternative Songs chart, and they played another song, “Loudspeaker,” on The Tonight Show that same year. But in the fall of 2021, MUNA returned to the Hot Rock & Alternative Songs chart with “Silk Chiffon,” a new single which features Bridgers.

Though they’re the only Saddest Factory signees with prior major label experience, MUNA’s members balk at the notion that they’re established: “In certain ways, we do still feel like up-and-comers,” McPherson says. So when the group’s manager told them about Saddest Factory while Bridgers’ label was in its embryonic pre-announcement stages, they kept it in their back pocket as a potential future home. Hickey, on the other hand, heard about the label directly from Bridgers. “We were talking about it for a long time before it happened,” he says. “From the beginning, I was just like, ‘Yes, of course. I'll follow Phoebe wherever she goes.’”

“Music kind of can’t help but be a community,” says Bridgers.

It’s one thing for Bridgers alone to insist she’s in this for the sheer joy of helping the musicians she loves attain more exposure, but it’s another thing entirely to hear the musicians signed to Saddest Factory organically, genuinely attest that Bridgers offers them an unbeatable support system, invaluable promotion, hands-on attention, and plain old compassion (not to mention, you know, passion) that they just can’t get from other labels. They see Bridgers as an inspiring, guiding figure whom they fully trust and can turn to whenever they need anything. Indeed, with Saddest Factory, Bridgers isn’t in it to make money off random musicians with hit potential. Instead, she’s giving a formal structure to her community of the past and present and putting it on the map in a big way.

“It feels like the label was born organically out of [Phoebe’s] friendships and musical community in LA,” Hickey says. “Most people don't have the experience of growing up knowing their A&R their entire life.” Dahl sees Saddest Factory as Bridgers doing her best to maintain a real sense of community, even as the music industry demands that the art it promotes be adorned with price tags and other artificial signifiers of value.

“The label itself is a community, but I also feel like the listener is [part] of it. I see them interacting with each other in a way that feels more organic, sincere, and excited than when I see other labels posting band stuff.”

— Haley Dahl

The label signees newer to personally knowing Bridgers also find a deeply meaningful circle of connections within Saddest Factory. Claud says that a sense of community was the single biggest asset the label offered them, as it was something they couldn’t find elsewhere. They say that on a recent tour, “When there was a bump in the road of any sort, I [had] a community of artists that I could call and get advice from. And that's really, really special and unique.”

“I definitely am available for phone calls or whatever from the homies if they need it,” MUNA’s Gavin later tells me. Her gesture is rooted in genuine human connection, as are all things Saddest Factory Records. The ties were already there, largely with an LA basis. Now, with Saddest Factory, Bridgers is helping her circle spread its roots across the world. And that’s entirely by design.“If you don't have connections,” Bridgers says, “It’s really hard to break through.”

Vore is a big part of what holds the label together, despite not being officially part of it. Bridgers describes Vore as basically an “under-the-table label employee,” and later jokes, “I probably should be paying him.” Hickey tells me that, since Vore’s studio is in Pasadena about five minutes from his house, “There's a lot of, like, ‘Can you come over and sing on this right now?’” It’s basically friends hanging out and, in the process, making art that Bridgers can more easily bring out into the world. Hickey says he’s friends with everyone—“even the [people] I’ve spent less time with”—signed to Saddest Factory. Of Hickey, Claud says, “I feel like I know [Charlie] so much ’cause we're always texting.” MUNA’s McPherson says they definitely see “a sort of artistic community” in LA, “and I think [Saddest Factory] is for sure part of that, and I'm very pleased to be part of it.”

“When there was a bump in the road of any sort, I [had] a community of artists that I could call and get advice from. And that's really, really special and unique.”

— Claud

The online presence of Saddest Factory Records resembles a deeply uncanny valley. Visitors to its website must “log in”—really, just click a button—to access it. Once you get through, you’re not greeted with well-lit, artistically staged photos of musicians and album artwork as on other label websites. You instead see something resembling a Mac desktop screen, with folders on the bottom labeled, among other things, “Morning Briefings (Don’t Leak),” “Company and Employee Handbook,” and “Not Porn” (that one is currently Claud’s “Guard Down” video, which is, indeed, not porn). Other folders take you to an “intern calendar,” the Saddest Factory store, and “Employee of the Month” plaques honoring the label’s signees. Messages from Bridgers occasionally populate the right-hand side: a “Where the hell is my oat latte?!” here, a “What time is office exercise class?” there.

Dahl has noticed that Saddest Factory’s internet presence helps listeners feel more welcomed into the label’s community. “I don't see a lot of record labels being creative with their online presence, and that can be a missed opportunity,” she says. The label’s social media presence, she continues, “has more of an interactive and inclusive feeling that creates a really good community space for people interested in the label.” She adds, “The label itself is a community, but I also feel like the listener is [part] of it. I'm not interacting with a bunch of strangers on the internet, but I see them interacting with each other in a way that feels more organic, sincere, and excited than when I see other labels posting band stuff.”

That sincerity extends to how Bridgers treats the artists on her label. Saddest Factory Records’ signees consistently say that Bridgers is always supportive, as well as fully tuned into what can make traditional record labels and music businesses problematic, and does all she can to avoid those pitfalls. “I think the best you can do when you're in a position like Phoebe’s,” says Dahl, “is to uplift things that you think truly deserve it.” Which, she adds, is exactly what Bridgers is doing. The label’s other signees unanimously agree. “She's not doing it to market herself,” Claud says of Bridgers. “She's really doing it to use her platform to elevate other artists.” Saddest Factory artists all attest that they’ve never felt like Bridgers is using the label to promote herself over them or earn another dollar. Instead, she’s sharing her years of accumulated marketing knowledge with her musical community in LA and beyond. Hickey says it best: In his eyes, Bridgers has “made a career for herself in such a cool and organic way solely based on her art and being true to herself, and she knows how to help somebody else do that.”

“Lead with your best thing, whatever it is. Don't lead with what you think is going to be the radio hit.”

— Phoebe Bridgers

Perhaps the most obvious manifestation of Bridgers’ supportive ethos is that Saddest Factory Records isn’t as fixated on streaming as other labels. “It's more than the immediate numbers that build a career,” Dahl says, “and that's something that Phoebe really understands.” MUNA’s McPherson puts it even more bluntly: “We've never had a single conversation about streaming.” They confess that this statement is a slight exaggeration: The label does deliver MUNA good news about its streaming figures, but that’s as far as the conversation goes. More importantly, Bridgers and her label never demand that the trio reach certain numerical thresholds or prioritize certain streaming-friendly tactics or sounds.

“If people believe 100 percent in what they made,” Bridgers explains, “then the marketing and streaming come later.” She says her focus is on carving a space for her favorite musicians to make the music they want to make without being told, for example, “I wish this chorus went a little harder.” That’s a real thing Bridgers heard at a label marketing meeting once. “I never liked having those kinds of conversations, and I feel like they're pretty shallow.”

Unsurprisingly, at Saddest Factory, those conversations don’t happen. Instead, as Hickey tells it, Bridgers’ viewpoint is, “Lead with your best thing, whatever it is. Don't lead with what you think is going to be the radio hit.” Bridgers couples this stance with hands-on guidance, which her signees say just isn’t possible to get from A&R representatives who haven’t played in bands, toured the world, and calculated yearly budgets based on the extremely low payouts associated with streaming. When Claud first discussed the label with Bridgers, they wound up “talking about how it’s so hard to trust A&Rs and people who work at labels ’cause they've never been in your shoes.” They say they “absolutely trust Phoebe and her advice, because she's been there.” MUNA’s Maskin adds that the trio’s caring, attentive Saddest Factory experience contrasts how, in the major-label ecosystem, they sometimes felt “lost [in] a sea of other artists.” But when you’re part of the Saddest Factory Records community, LA-based or not, you matter.

The label can be viewed as a sheep in wolf’s clothing: a supportive community disguised as a traditional institution that’s not always the most artist-friendly. “It’s a really weird thing to be selling your art,” Bridgers confesses. “It’s weird and shitty.” But if the feelings of the artists she’s helping are any indication, the selling isn’t the point. Supporting and promoting the community is what matters most—and that’s exactly what Bridgers is doing. FL