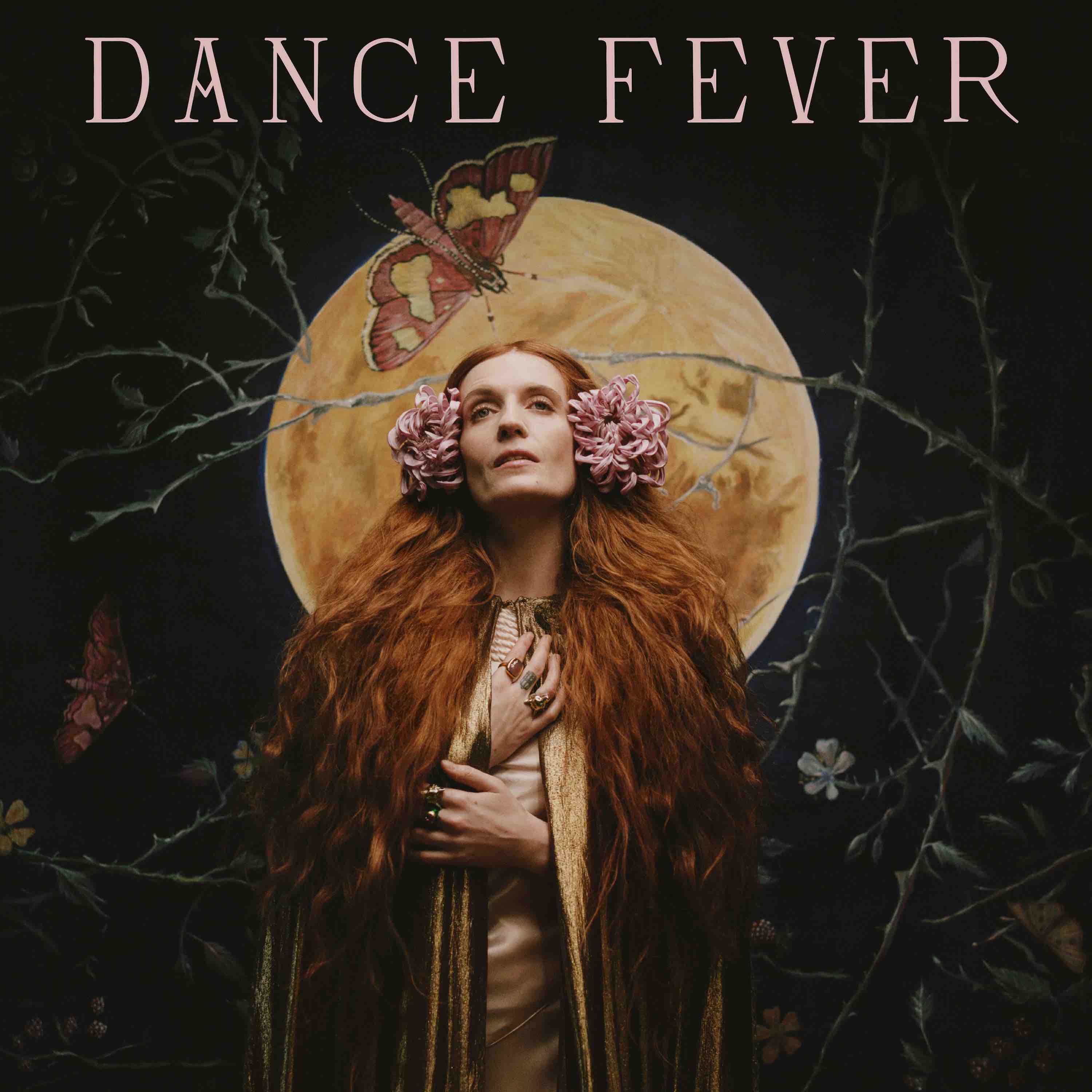

Florence + the Machine

Dance Fever

POLYDOR

ABOVE THE CURRENT

For what feels like the first time, Florence Welch refers to her songwriting persona with tongue-in-cheek detachment on “King,” even as she defends her devotion to her career: “I need my golden crown of sorrows / My bloody sword to swing / I need my empty halls to echo with grand self-mythology.” It comes during an argument in Welch’s kitchen about whether to have children, which finds her declaring her distaste for the archetypes of femininity: “I am no mother, I am no bride / I am king.” On the last Florence + The Machine record, 2018’s High as Hope, Welch took a first real stab at writing literally about herself, the woman beneath the melodic force of nature that moves her. On her fifth, Dance Fever, she wrangles both sides to the same table and births some of her most compelling songs in the process.

Named for a mass psychogenic illness from history that drove people to dance themselves to death, Dance Fever is a post-plague meditation on control. The tension between self-mythology and self-destruction has always underpinned Welch’s songs—at least as far back as “Hurricane Drunk” and as recently as “Hunger”—and here it manifests in the joy and grief of “Choreomania,” the sense that the irresistible compulsion to make music might, at best, be keeping her from other ways of being, and at worst, physically killing her. It’s why the king she most identifies with is Elvis, in all his glory and in his ungraceful descent from the throne (“Morning Elvis”). The beats are more physical than ever, with hooks built on handclaps and crackling electronics, and the lyrics are darkly comic (“’You're too sensitive,’ they said / I said, ‘OK, but let’s discuss this at the hospital’”), all in service to that thrilling feeling of dancing on the edge of a knife.

Welch wonders aloud whether she’s learned restraint, and in the grand tradition of Lungs, Dance Fever has its disco dramas (“My Love”) and fantasy film trailer fodder (“Daffodil”). But even at its loftiest, it comes with a newfound realness, and even wit to ground its spoken-word verses and medieval-inspired interludes. In fact, you can best feel the overwhelming power of her ambition when she holds it back with an iron fist, as on the awe-inspiring, mid-tempo march “Dream Girl Evil.” It’s a stunning display of the control she can wield in the realm of music, in spite of whatever male fantasies are projected onto her; here, the drums and acoustic guitars tromp forward like armor-clad boots at her command.

Dance Fever ends with the clamor of a waiting crowd, the nagging question—whether she can go on taking the stage—still up in the air. For these 14 tracks, though, Florence Welch the songwriter, majestic and messy and mundane, can have it all.