In the summer of 2012, I’d just finished junior high school. I was chubby, freshly weaned-off ADHD medication, sludging way too much gel into my hair, desperately yearning for someone to post a romantic “TBH” on my Facebook wall, and a proud believer that Drake’s Take Care was the best album ever made. Some months prior, on New Year’s Eve 2011, I wrote “WE WON’T DIE IN 2012” backwards on a piece of notebook paper, taped it to my Big Bang Theory “Bazinga” t-shirt, snapped a bathroom mirror selfie before Dick Clark’s countdown, and posted it on Facebook in hopes a crush would like it. But, as the glittering sphere that fell into Times Square carried promises of another year forward, I’m often thinking backwards, always reckoning deeply with moments from my past where I encountered certain kinds of magic I still can’t properly articulate the electricity of.

Despite the proto-meme John Cusack vehicle named for the year, which conjured oversaturated worries to mass audiences three years prior, there was something so alive and beautiful in the air which swirled above our heads in 2012. I spent the year’s dizzying turn with no friends or fleeting romances. I’m not nostalgic for who I was during the apocalypse’s prologue, only for how I felt during it, because sometimes we so badly just want to be alone but are too scared to say it. So, even with the Mayan calendar ending and the dreaded sundown of a particularly glamorous and commodified doomsday creeping onward, 2012 managed to gift us with its greatest document of honesty, over-feeling, and loneliness: Fiona Apple’s The Idler Wheel Is Wiser Than the Driver of the Screw and Whipping Cords Will Serve You More Than Ropes Will Ever Do.

I was late to the Fiona Apple game. Born two years after she released her 1996 debut, Tidal, her work is definitive for the generation that came before mine. But Fiona’s mythology immediately floored me in college. The stories of her ditching blow after hanging out with Tarantino and PTA, riding NYC subways in full medieval armor, calling the popular-culture-conforming world “bullshit” at the 1997 MTV VMAs—they all raptured my undeveloped late-teenager brain. Her reclusivity and non-existent social media presence was a template I’m still reaching for in 2022. It was something about that Kurt Cobain quote, the “adoration of John Lennon and anonymity of Ringo Starr” one-liner that felt indicative of the persona Fiona had long-cultivated.

There are things from my teen years that still often sing within me: my folks happily dancing to The Bee Gees on our back deck before my dad lost his job; a crush twirling herself around the notes of a Passion Pit song during a fireworks show; lamely queuing Sublime’s discography while ripping dabs before the homecoming football game; starting hormone therapy before I even had a learner’s permit. Unexpectedly, I graduated from Judgment Day conspiracies to mental illness, which offered me new flickers of mortality, new pain to feel suddenly and deeply. I’d never met another person taking testosterone and couldn’t find another intersex person to find hope in. A world I’d once gullibly bought into the ending of had never felt so small.

It’s rare to listen to something and learn how to live from it, but Idler Wheel is what I imagine hearing your identity brought to sonic life must sound like for others.

And it wasn’t until 2020—when the world was faced with another prospect of pronounced finale—that I remembered the magic Fiona struck deep within me after I’d lost it. She released Fetch the Bolt Cutters on the one-month anniversary of COVID lockdowns in America while I was actively feuding with my insurance company over testosterone prescription renewals. My understanding of Bolt Cutters is that its singularity often rests on the shoulders of the Earth-spanning narrative it was unintentionally born alongside. As a music critic and occasional reviewer, I’m always considering how the subjectivity of a particular piece of art rubs shoulders with the timeliness of its release. When Fiona sang “I know none of this will matter in the long run / But I know a sound is still a sound / And while I’m in this body / I want somebody to want,” it hit too close to home. At the time, I was doubting my own radiance, because my then-partner was struggling to articulate desire toward me while we were quarantined away from each other.

When Bolt Cutters spilled onto our laps in the early teeth of the pandemic, the hominess of its sonic palette, the way it coiled and unfurled so extensively within the confines of a familiar vacuum, filled an emotional need we didn’t know would stretch so far into our futures. The mass-critical acclaim that followed matched the moment—I can’t speak on how the record would score in 2022, but I’m often wondering how The Idler Wheel would’ve scored had it taken its place instead.

I can’t pinpoint the first time I heard Idler Wheel. Songs from it have found themselves in various moments in film and TV, but, when I discovered Fiona’s fourth record, I was at college, finally embracing my queer little self, identifying openly as intersex, and no longer hiding my hormone therapy. For the first time, pumping testosterone into the soft spots of my stomach with an insulin needle felt beautiful; having a concave chest and widened hips became sexy; what little facial hair I’d grown felt masculine enough. Fiona’s music provided a good soundtrack for that newfound ecstacy.

It’s rare to listen to something and learn how to live from it, but Idler Wheel is what I imagine hearing your identity brought to sonic life must sound like for others. The album itself is about self-love versus self-hate, feeling things fully, and confidence beyond grief. I remember standing in a pencil skirt in my partner’s dorm room during freshman year, mere days after my grandma passed away, and for the first time feeling overwhelmed by the grandeur I’d unshelled. The friends I met on campus encouraged me to embrace the fluidity I’d only ever flirted with. With painted nails and eye-liner on, I’d study myself in the mirror, slowly moving my body like a ballet, dragging my thin, boney hands across my stubbled face. On Idler Wheel closer “Largo,” Apple’s octave-jumping chorus sounds like a rendering of that, as if a ballerina is gently twirling from one side of a stage to the other, as if a light is flickering a delicate morse code into one’s soul.

Fiona’s opus demonstrates the beauty and power of choice—how you can declare to love every bit of yourself by living deeply within it.

“Every Single Night,” Idler Wheel’s opener, is my intersex totem, as I wrestle with autonomy nine years deep into an indefinite hormone therapy. So much of my life, and the way I process my own queerness, has come via the way I and others interpret a body. My community is still advocating for the abolition of at-birth intersex surgeries; I’m still trying to convince comment sections that you can have a dick and no Y-chromosome. I don’t just exist on a spectrum; I am a spectrum, and I’m trying to love each end of it. Fiona plays with that optimism on “Every Single Night,” which is, at its core, about self-doubt and the machinations of one’s own sabotaging chemical imbalances. “If what I am is what I am / ’Cause I does what I does / Then brother get back / ’Cause my breast’s gonna bust open / The rib is the shell / And a heart is the yolk,” she sings in the pre-chorus.

Yet Idler Wheel isn’t just an artifact of my own gender euphoria; it’s an articulation of familiar emotions, of being healthily in love with the body at rest. For so long I wanted to embrace everyone else without confronting my own needs, but Fiona’s opus demonstrates the beauty and power of choice—how you can declare to love every bit of yourself by living deeply within it.

I didn’t understand that mantra when the person I fell in love with left campus for Scotland for the spring semester, which is probably why “Werewolf,” a track about confronting your romantic demons, brings me back to this headspace. It was the first time I let myself authentically crush on someone without being tethered to cisgendered heterosexuality. They set a fire within me, but I never got to tell them that. When they returned to campus in August, our hearts had capsized, the passion and trust had fallen away, and Fiona singing “The lava of a volcano shot up hot from under the sea / One thing leads to another / And you made an island of me” through the bridge became such a tendril. I thought our dissolving had been my fault, that my bizarre body was too bizarre, or that I’d loved them enough to idealize a specific future but not nearly enough to keep a present afloat, and the sparseness of Fiona’s instrumental brought sonic life to that loneliness and those unanswered questions.

I turned to Fiona’s piano balladry often when I was two weeks deep into bedrest after catching an uncategorical illness during March of my freshman year. It was a superorganism-like ailment, a hyper-mono that left me with an eating disorder. I was so weakened by malnutrition I thought I was going to die. I’d listen to Idler Wheel in-between sweat-soaked bouts of unconsciousness. Missing class and dorm-floor hangouts while feverish in bed was debilitating emotionally; the FOMO that ambushed my brain immediately contradicted the “How can I ask anyone to love me / When all I do is beg to be left alone?” line on “Left Alone” that perfectly articulated the escapism I’d been chasing since 2012. While my partner was in class, I felt unlovable, like a dead weight. It was like my world was ending, but I still had the bliss of being sick in a familiar body. When foodless days quickly devoured the plumpness testosterone had put in my gut, though, I fully lost the fluttering, hormonal grace that had so recently set me free.

Fiona’s songs aren’t distilled, but humanly flawed. And she leans into those flaws with a ceaseless-yet-placid splendor worth replicating a thousand times over.

It was hard making sense of the period that came after that. I’d lost 30 pounds in a month and couldn’t stand up for longer than 20 minutes at a time; summer break was nearing and I’d hoped for more time with everyone, because I believed that remembering how to love yourself was not a solitary act. “I’m a tulip in a cup / I stand no chance of growing up,” Fiona sings in the chorus of “Valentine.” I’d spent so much of my time on Earth in a vacuum, living in fear of fragility and in fear of having to tumble through being intersex alone in a community of non-intersex people. A part of that worry likely stemmed from having needle caps break under skin in front of roommates, or hiding a stomach covered in red hormone welts. When something is considered taboo, the shame it brings often knows no healthy bounds, and I thought that was a doomsday in itself. Five years later and I’m still putting the pieces I lost back together, slowly gaining back the weight that deserted me.

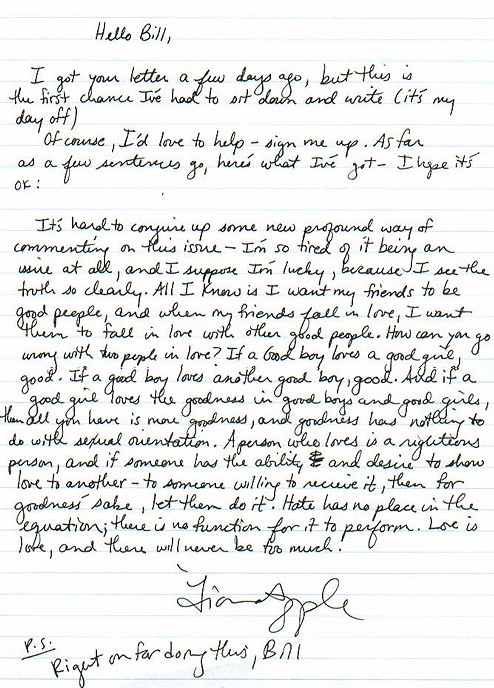

But what I remember most about discovering Fiona Apple’s legacy in undergrad was reading a letter she handwrote to a young gay fan of hers in 2000. It read: “A person who loves is a righteous person and if someone has the ability and desire to show love to another—to someone willing to receive it, then for goodness’ sake, let them do it.” I had to leave college to finally understand that I could be both the one showing love to another and the one willing to receive it. That’s what Idler Wheel is about, and returning to the record on its 10th birthday, I’ve finally fallen in love with its singularity and realized how I thought the affection of others would unlock my body’s destiny. How naive of me to not see the rigid, raw, autonomous ocean of Fiona’s musical ecosystem living beneath her lyrical balm; how naive to think in 2012, 2017, and 2020 that what crumbled before me was even an entire world at all.

Maybe that’s why the most important moment from Idler Wheel, to me, arrives at its very end, when Fiona asks, “And how could I listen without wanting to be with them? / And how could I have thought I was ever alone?” It’s a callback to “Left Alone,” but it’s also a hopeful resolution. A coda to her most personal composition, she sings about the duality of doubt, how you can be so foolishly dependent on others and aware of what fullness can thrive inside the lonesome. Fiona’s songs aren’t distilled, but humanly flawed. And she leans into those flaws with a ceaseless-yet-placid splendor worth replicating a thousand times over.

The Idler Wheel is the only piece of art that’s shown me what a joy it is to feel fully alive in an always-changing but perfect intersex body. Before the record found me, I’d measured my presence in this world by how visible I was to others and how much they loved me. Now, when over the rainbow’s too far, I return to Idler Wheel and remember how to reach inward with joy and savor what’s discovered. FL