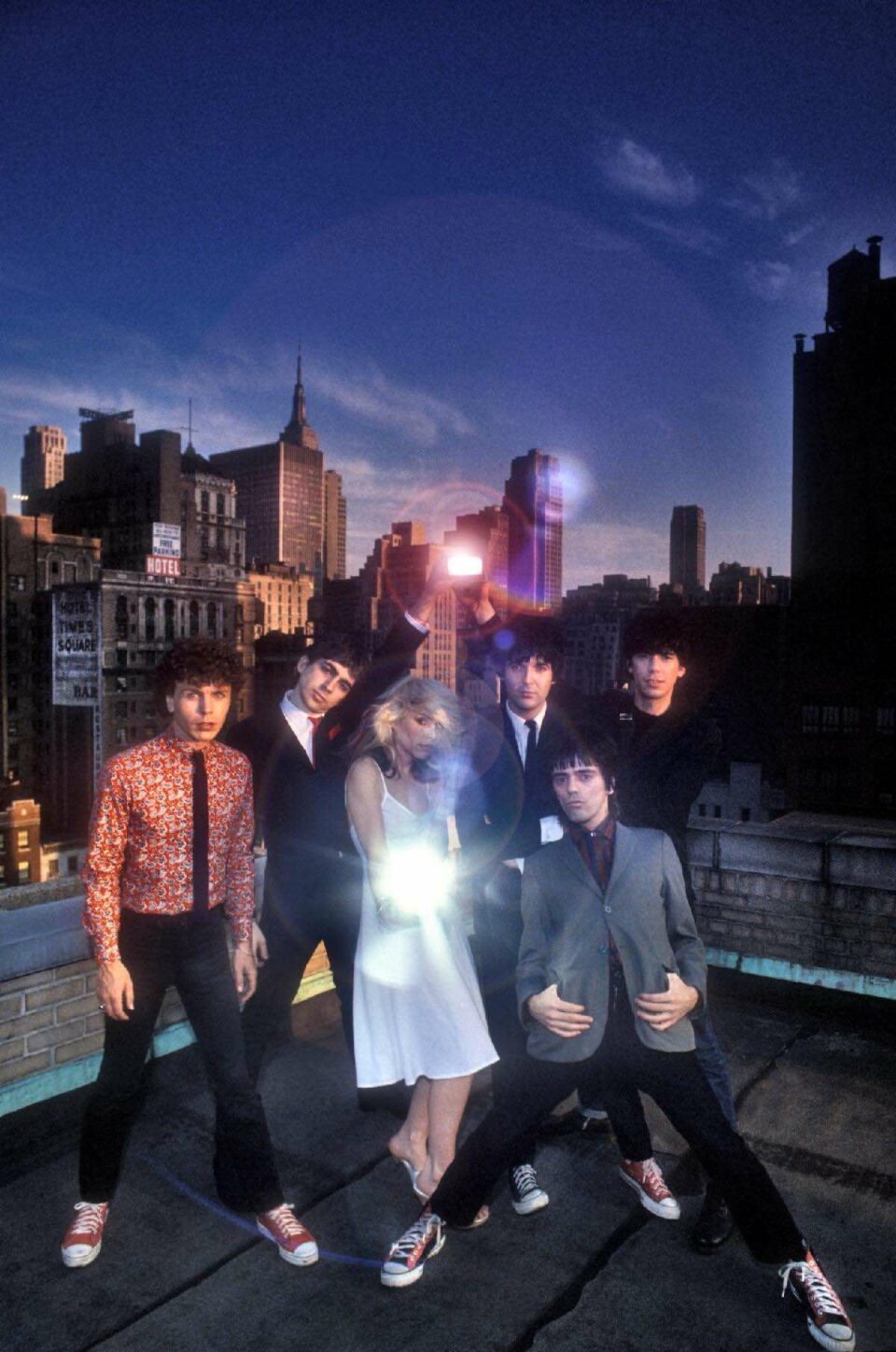

The other night, I watched intently as Blondie pulled out all the stops in a live setting near downtown Philadelphia for two hours worth of pre- and post-punk and disco hits, as well as new material from recent albums such as 2017’s Pollinator. Two things became very clear about the currently Chris Stein–less ensemble that is Blondie in 2022: that Debbie Harry’s alluring, noir-ish vocal demeanor hasn’t wavered since the first time I spied them in NYC before their first album came out, and that Clem Burke remains the master of his swing pummeling style of drumming—the groove that marries Gene Krupa to Keith Moon, yet remains personal, energized, and iconic.

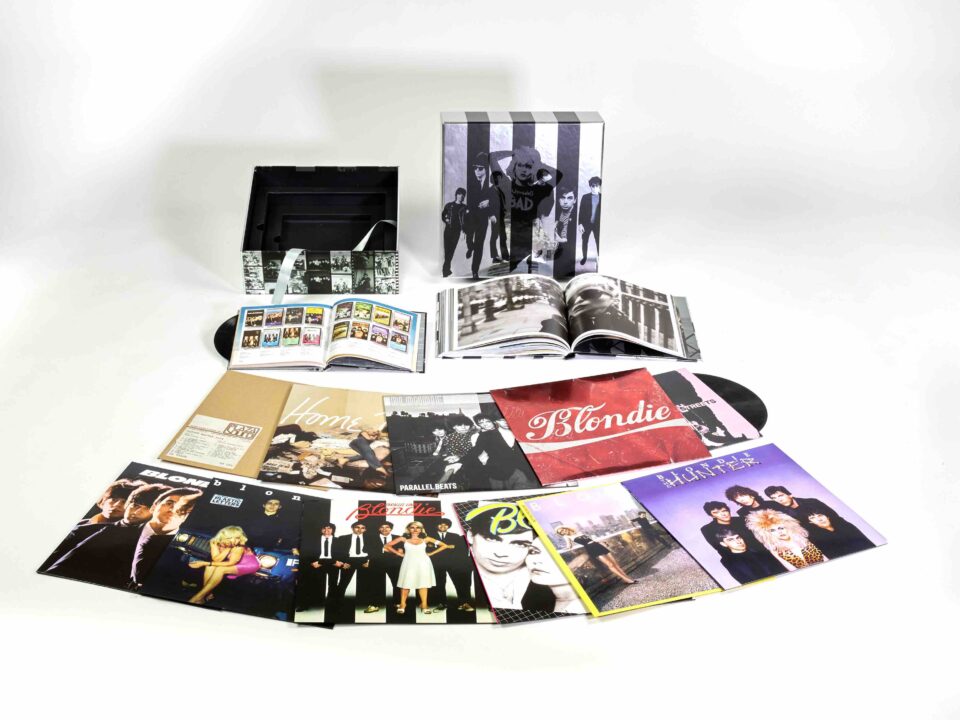

On the precipice of releasing an epic eight-LP box set of their first six albums and never-before-issued pre-band rarities with Against the Odds: 1974-1982, Burke spoke with us about what it means to eat to the beat, break the bank, craft his own drumming brand (even up against the early drum machines of “Call Me”), and generally make a rhythmic ruckus for Blondie going on 50 years.

Harry, Stein, and you are all that remain of the original Blondie. What was the circumstance of getting to know them in the first place?

There was a club on East 4th Street in New York, Club 82. That room was the precursor of what would eventually happen at CBGB, but more about glam rock, Wayne County, and the New York Dolls era.

Everyone then was a Dolls fan, and dressed like one.

Oh yeah. Worshiping the Dolls who, along with The Velvet Underground, were the two touchstones of bands in New York at that time. They influenced all of us back then. I had a group that played around that glam scene at the same time Debbie and Chris had their band, The Stilettos. I would run into them at 82 and Max’s Kansas City.

“I was actively looking for someone who had a certain level of creativity and charisma. Someone along the lines of a Bowie. When I met Debbie, she was that person.”

We crossed paths constantly until, famously, Chris and Debbie put an ad in the back page of the Village Voice for a drummer without giving their names. I did, however, surmise it was them. We got together at their rehearsal space on West 30th Street, just blocks south of Madison Square Garden. There was a lot of common denominators between us in terms of influences—The Shangri-Las, Iggy & the Stooges—and what we wanted to do musically going forward.

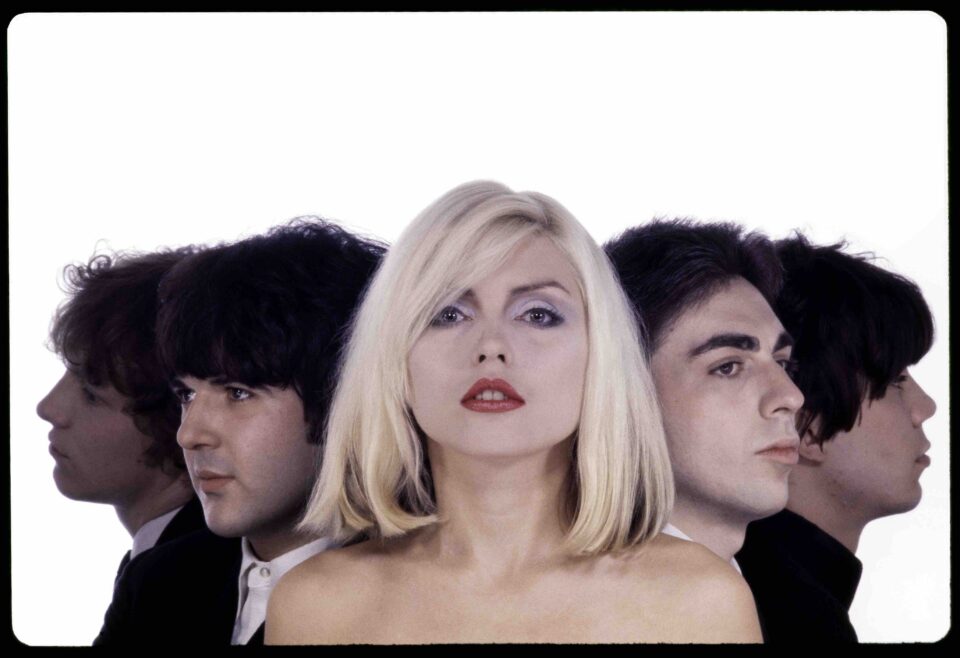

Were you actively looking for a Debbie Harry?

I was actively looking for someone who could front a band, someone who had a certain level of creativity and charisma. Someone along the lines of a Bowie. When I met Debbie, she was that person. I knew that.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that any band you would play with had to be able to contain this propulsive level of drumming that you make your own—a Keith Moon, for example.

Moon was one of my big drumming influences along with Ringo Starr and session drummers such as Hal Blaine and Earl Palmer, the guy who famously played on Eddie Cochran’s “Something Else” and Little Richard’s Specialty [Records] material. Those guys were unknown to most, but played on all of the records I loved as a kid. Earl Palmer was propulsive, a jazz musician who became crucial to rock ’n’ roll—a true architect.

Upon arrival into Blondie, you brought bassist Gary Valentine with you after Fred Smith—who wound up in Television—split.

I did, even though Gary was not really a trained musician, per se, and certainly never played bass before that. He knew a few chords on the piano, but I knew he had style, so I encouraged him to meet Chris and Debbie. He was actually a poet, and recited some stuff to them at that initial meeting. I was living at a storefront at that time with Gary, so it was all pretty convenient. We could negotiate New York City better that way. All the clubs were close by us, the Bowery in general. Max’s was just up the road a bit. It was easy to begin in the city at that time—very different, obviously, from what it’s become now.

“My drumming did connect the dots as far as creating a consistency in their arrangements and the sound of the band at that time. It was pretty raw—just Gary, Chris, and myself with Debbie up front. That gave me a lot of room to experiment.”

Without picking through every loose demo on the new box set, how would you say you changed Debbie and Chris’ feel?

I had a real appreciation for their songwriting. My drumming did connect the dots as far as creating a consistency in their arrangements and the sound of the band at that time. It was pretty raw—just Gary, Chris, and myself with Debbie up front. That gave me a lot of room to experiment.

You can absolutely hear that on the earliest demos on Against the Odds versus the official Private Stock label stuff on the albums that would follow.

Going back to Keith Moon, in the context of The Who, he filled up space. Especially with [Pete] Townshend playing quite a bit of rhythm guitar. Moon filled in the blanks. That was my approach to Blondie with all my fills within the context of a rock ’n’ roll trio. There was quite a bit of room for me to expand my playing, and I took advantage of that—but we were also following each other in experimenting and filling out the arrangements.

At some point, Blondie begins using a drum machine on some of its more prominent tracks. How did you work within that context?

Everyone was using that same Roland drum machine at that time. The one we used was the same one Roxy Music used on “Dance Away,” the same one Phil Collins used on “In the Air Tonight.” You just had to be open-minded in the context of working with a group of people. You have to be open to new technologies. Which everyone in Blondie was.

With “Heart of Glass,” we were showing off how big of fans of Kraftwerk we were with our experiments in sequencing. In general, though, you have to appreciate what everyone is bringing to the musical table. I enjoyed working with synthesizers and sequencers in collaboration with my live drumming—still do on our newer music. It worked out particularly well on “Atomic.” That said, a lot of stuff you might think is sequenced or done to a click track, such as “Rapture,” is not. That was just me and a natural live drum groove in the studio that we built upon. All of the demos and early Blondie tracks were built from the bottom up, from a drum track through to becoming the trigger for a fresh arrangement.

“You could make the analogy of a brother-sister relationship between me and Chris and Debbie. With that, you can’t always agree to everything, but we probably do agree more than we disagree as time went on.”

You’re the only constant of Blondie’s line-up save for Debbie and Chris. Why?

There’s a lot of reasons for that, I think. Go back to the genesis of Blondie. This was just Chris and Debbie. When Fred Smith left, I was keen to keep the band going—Chris and Debbie, at that time, weren’t. They were pretty disillusioned as they’d been doing music for a while at that point. Fred leaving for Television and Ivan Kral leaving for the Patti Smith Band, Debbie and Chris thought that this was the band. They felt abandoned, as if all of these musicians were de-camping to other groups.

I, on the other hand, had this firm belief in what Blondie could be: the songs and the possibilities. I encouraged them to move forward. They’re slightly older than me, so you could make the analogy of a brother-sister relationship between me and Chris and Debbie. With that, you can’t always agree to everything, but we probably do agree more than we disagree as time went on. For some reason, we’re partners for life. Plus, I brought my aesthetic of a love of all-thing ’60s—bubblegum, power pop—and that stuck and became part of the Blondie style that wasn’t there before I came on the scene.

Is that also down to their personal style at the time of the band’s start?

I was responsible for finding a lot of the clothes that we wore. I can remember bringing in these immense trash bags of ’60s gear that a friend of mine had—he had an Army/Navy store that was going out of business, and I raided it to outfit the band.

Want to say something about your favorite previously unreleased track on Against the Odds?

That’s tough. Chris has always been a hoarder-collector, so he’s the band’s archivist. Probably the raw demo of “Platinum Blonde,” because that was forever one of Debbie’s signature songs, and it somehow never made it onto any of our albums. Other than that, even rehearing the hits is great. We’ve somehow become part of the American fabric, one where you can hear Blondie in the grocery store. FL