As of writing this, only one name appears in the “Style and influences” section of Open Mike Eagle’s Wikipedia page: They Might Be Giants. The LA-by-way-of-Chicago rapper’s hip-hop lineage isn’t nearly as remote as that implies when you consider his early work with West Coast crew Project Blowed, his admiration for (and two collab tracks with) the late-great MF DOOM, and his efforts to record oral histories of the genre on the What Had Happened Was podcast with figures like Prince Paul, El-P, and Dante Ross. In his recorded catalog, though, there's a segment of influences that sometimes gets overshadowed by the genre tag he coined and used to title his 2010 debut album: Unapologetic Art Rap.

His eighth record, a tape called component system with the auto reverse, aims to put some of the “rap” back in “art rap” and mythologize the underground hip-hop that first inspired him as a teenager in the mid- to late-’90s. “There’s a lot about my approach that’s informed by that music that people aren’t aware of, and I really wanted to give a lot of voice to that,” says Eagle via Zoom. “When I was putting this music together, I was definitely thinking more beats in the traditional sense versus a lot of the electronic experimental musicality that informed some of the music I’ve used before. I definitely wanted beats to rap to. Like, that was a prime directive.”

He comes out mic blazing on the horn fanfare of opener “the song with the secret name,” but you get the best glimpse of the young Eagle—who started out freestyling on stages, street corners, and at Chicago’s Promontory Point—on the Quelle Chris–produced “79th and stony island,” named for the intersection where he lived at the time. On school nights, Eagle would fall asleep recording the 9 p.m. to midnight show on local college radio station WHPK through his stereo, a “Pioneer six-CD-changer dual-cassette auto-reverse shelf system,” he remembers. Those tapes brought him heroes like DOOM and Diamond D, interspersed with the voices of local DJs like Ice Box, who’s sampled on “stony island” introducing “Me, Not the Paper” by Jeru the Damaja. “I can say that, too, I do this for me and not the paper,” Ice Box ad-libs in his classic and clear radio voice. “There is no paper here.”

“When I was putting this music together, I was definitely thinking more beats in the traditional sense versus a lot of the electronic experimental musicality that informed some of the music I’ve used before. I definitely wanted beats to rap to. Like, that was a prime directive.”

“I loved how he said that off the cuff,” says Eagle. We laugh about that context, the way it was spoken one night into the ether to no one in particular—but as in his music, any absurdity comes from underlying truth; Open Mike Eagle can also say that he raps for himself, even as the money comes and goes. His sense of humor, his personal trauma, his love of wrestling, or cartoons, or high-concept, comic-book-influenced narrative—the things he’s become known for sharing are all his own, but his passion and bold, independent spirit also come descended from indie-rap forebears. “I thought that was so smooth, and that’s the thread that I’ve followed since then,” Eagle reflects. “That's the throughline to my career.”

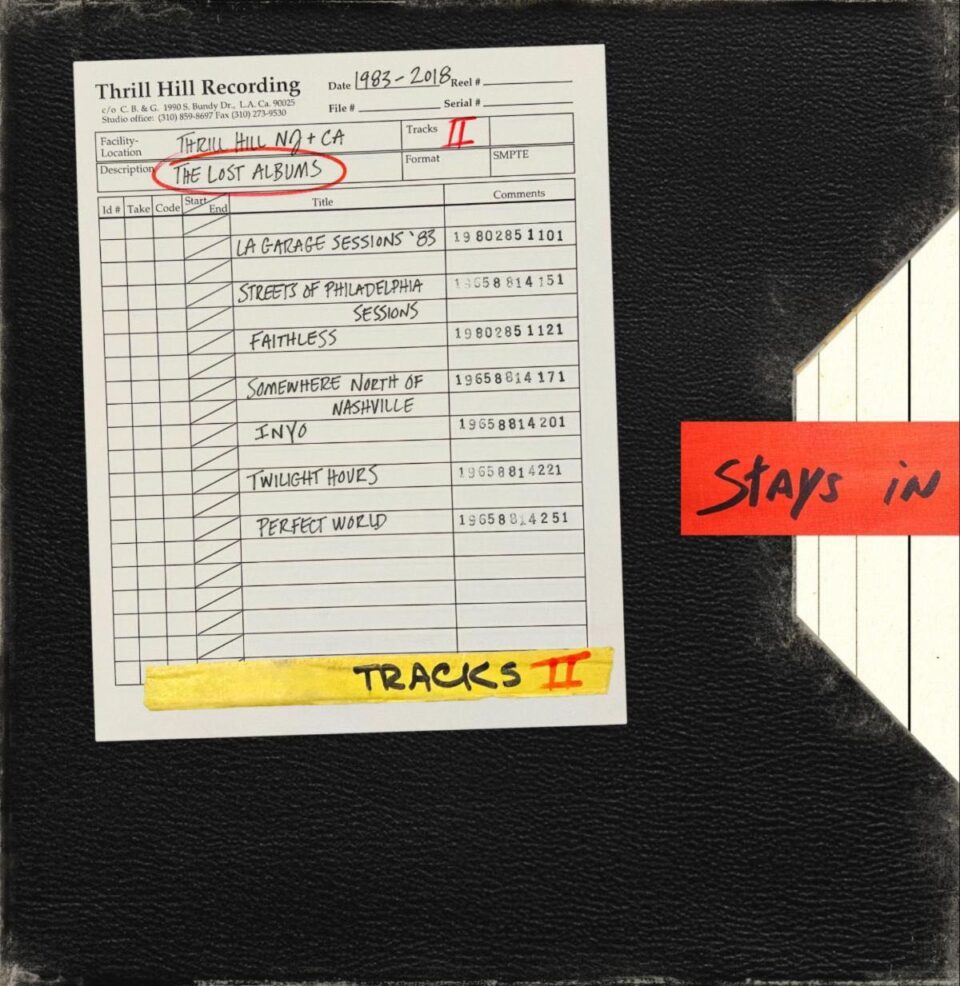

He structured component system to replicate the feel of the second-level tapes he’d make from WHPK broadcasts, which compiled the best songs from his overnight recordings. Titles like “TDK scribbled intro” pay tribute to the medium of the homemade mix, and the sounds of spring-loaded stereo doors signal the beginning and end of the album. “Over the course of making this record, I was buying a lot of old stereos off eBay,” Eagle explains. “I wanted to be around that technology. I really wanted to see it, put my hands on it, and hear the tape doors opening and closing. Even just visually, it comforts me to see these things that were such a big part of my life at a certain time.”

You could say he got into an analog headspace, especially in creating the album cover, where Eagle found a unique use for one of those eBay stereos. “It occurred to me that I could probably get my head in there because it was big enough,” he says. Prop-maker Elaine Carey, who previously crafted the butt-head headpieces worn by Eagle and Video Dave in the visual for their 2020 single “Headass (Idiot Shinji),” transformed it into a helmet. I ask Eagle about the plan for that piece now that the album cover’s been shot. “People will see that version of me more, for sure,” he says, leaving it at that.

“Over the course of making this record, I was buying a lot of old stereos off eBay. I wanted to be around that technology. I really wanted to see it, put my hands on it, and hear the tape doors opening and closing.”

For all its old-tech trappings, though, component system isn’t an easy nostalgia trip. Eagle reckons with the heartbreak of losing an idol on “For DOOM,” and on songs like “I retired then I changed my mind,” he takes stock of his place in the present landscape of hip-hop, being very candid about the pros and cons of rapping for himself and not the paper. He wonders whether Unapologetic Art Rap was too bold an album title, and laments the paradox of having critical support without mainstream recognition. I ask him about one line in particular from “stony island”: “I’m in a weird place creatively.” How do you go on making music through that?

“I don't think I’ll ever be done creating. I think there’s something about songwriting and the infinite possibilities of that where I always feel like I have more to say, in one form or another,” he says. “I think that my eternal struggle is that I’m trying to sell what I have to say for a living, but often what I have to say is not mass-marketable. Oftentimes, it feels very individualized, and that’s the constant struggle for me; I’m in this industry where there’s a clear top and bottom, and I don’t enjoy being where I am.”

He elaborates, “Being a working-class rapper, there’s times where it puts you in a position to have very thrilling experiences, but overall, it’s a weird-ass place to be. I get to be true to my own creative whims, but there’s also economic ramifications to that. I think I’m finally seeing that the real problem is that I don’t have much of a budget, but right now I’m not making much that would cause anybody to give me a budget. I have enough budget to successfully put out an independent rap record, but I think every rapper wants to be big, and you can’t be big without a budget.”

“My eternal struggle is that I’m trying to sell what I have to say for a living, but often what I have to say is not mass-marketable. Oftentimes, it feels very individualized.”

On component system, at least, Eagle’s creative whims serve him well, and his indie “war of attrition” has its spoils. In addition to featuring all-stars like Madlib and Armand Hammer, making the tape connected him with Diamond D, who appeared on one of his WHPK tapes all those years ago. “Diamond D is an actual representation of the music that spiritually informed this album, and then he's actually on the album, too. I think once I was able to make that happen, it gave the thing a full shape,” says Eagle.

Their collaboration, “i’ll fight you,” became the record’s first single, and it showcases Eagle’s mature delivery, relaxed and melodic—the product, he says, of the home-recording trial and error it took to learn how to rap into a microphone after spending his formative years raising his voice to be heard in a group (“20 years in, now I know my own vocal range,” he observes on “I retired”). At the same time, you can imagine him back in the cyphers where he first learned how to rhyme, the echoey background vocal shouts—like his store of old tapes—cheering him on. FL