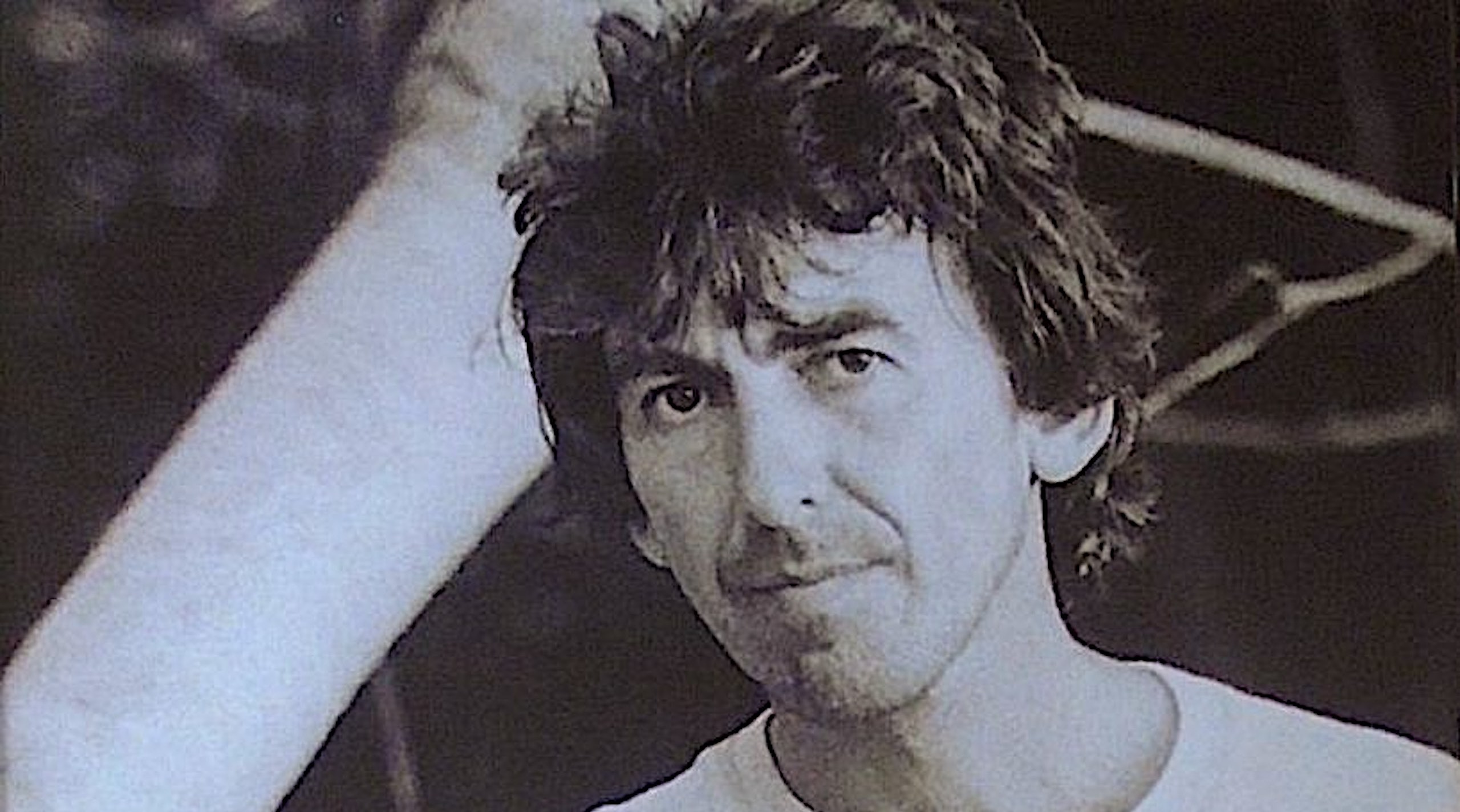

The idea of a posthumous release by a universally adored artist can come with a hanging asterisk that drips of dubious intentions. In some cases, it can seem like a predatory cash-in by the machine that surrounded the artist in their final days, looking for a quick payday rather than to preserve the artist’s wishes of leaving unfinished works unfinished. But in the best scenarios, these once-lost documents can act as celebrations of the narrative that could have been written if circumstances were different. With George Harrison’s 12th and final solo album Brainwashed, those closest to the Beatle made sure to handle his nearly finished album with care.

By the time the album finally reached stores 20 years ago on November 18, 2002, Harrison had been dead for just under a year after succumbing to a battle with lung cancer. The 1990s had been a period of letting off steam for Harrison, so to speak. His last true solo release was 1987’s Cloud Nine, which found him building a musical second-hand with Electric Light Orchestra’s Jeff Lynne. The two co-produced that album, delivering a new sound for Harrison which leaned heavily on the crisp, alien-like production Lynne had perfected on his quest to take the template The Beatles had left behind on the roof of Apple headquarters and launch it into a new solar system.

Apparently, Harrison had been tinkering with song ideas and working on tracks with Lynne throughout the decade in various sporadic studio sessions after Cloud Nine. But presenting something with his full name on the spine seemed like too heavy a prospect. He was looking to recapture the kind of mischief you can only drum up with a band. So instead, he and Lynne started the laughably stacked supergroup the Traveling Wilburys, which also featured Bob Dylan, Tom Petty, and Roy Orbison. Like The Avengers for the boomer generation, that group released two albums: Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 in 1989 and the mischievously titled Traveling Wilburys Vol. 3 in 1991.

But once that band decided to call it quits after the passing of Orbison in 1988 (in that sense, Vol. 3 was another posthumous release), Harrison gave time for his next batch of solo songs to materialize. However, that didn’t stop other enticing projects from taking his attention. He became heavily involved in the massive archival series Beatles: Anthology which featured a three-part documentary in November of 1995 and rolled out three double-album collections between 1995 and 1996. Subsequently, he also produced his musical hero Ravi Shankar’s 1997 album Chants of India. Skeletons of his own songs presented themselves during this time, but after barely evading death during a bout with throat cancer in 1997, as well as surviving an attack by a knife-wielding intruder at his home in 1999, he gained a focus to finishing what would surely become Brainwashed.

The songs on Brainwashed give you a greater sense of where Harrison wound up at the end of a long journey, the results showing both a sense of inner peace as well as frustration at the state of the world.

When the time came to really flesh things out with Lynne in the early aughts, he found out that the cancer he thought he’d defeated had reappeared in his lungs and had spread to his brain. Knowing that the finish line was in sight, Harrison confided in his son Dhani the true vision on how he would land the plane, giving Dhani detailed instructions on the record’s final arrangements, production, and even album artwork in the event of his inevitable passing. George, Dhani, and Lynne would work together tirelessly with a band of top-notch session musicians—such as Traveling Wilburys drummer Jim Keltner—up until Harrison’s passing in 2001. Once he was gone, Dhani and Lynne took the reins like they were instructed, even keeping up the original studio schedule Harrison made while he was alive.

Listening to the completed album and knowing the genuine intentions behind its final form, Brainwashed brims with an overwhelming sense of humanity. But in his own way, that always seemed like Harrison’s appeal in The Beatles when looking at the larger-than-life personalities of John, Paul, and Ringo. He’d always kept to himself, and his lyrics reflected his search through comfortability in the absence of ego aided by his awakening through Hinduism. In his best solo work, such as his previous high-water marks 1970’s All Things Must Pass and its 1973 follow-up Living in the Material World, he was able to distill concepts of spiritual enlightenment into pop songs just as well as love and rebellion were shoehorned in by the early architects of the artform. The songs on Brainwashed give you a greater sense of where Harrison wound up at the end of that long journey, the results showing both a sense of inner peace as well as frustration at the state of the world.

On the record, Harrison offers bits of hard-won wisdom as heard on the GRAMMY-nominated single “Any Road,” or the jangly anthem “Looking for My Life.” On “Pisces Fish,” he paints a picture of the human race’s continuous balance between labor and doing good in the eyes of a moral authority, whether that’s one of many gods or simply important figures in our communities. It’s a balance that Harrison admits he never quite got right as he sings, “I’m living proof of all life’s contradictions / One half’s going where the other half’s just been.”

One of Harrison’s most underrated musical abilities was his distinctly singular slide-guitar playing. Throughout the album, and especially with the GRAMMY-winning instrumental track “Marwa Blues,” he got the chance to show off his blissful and lyrical style at the peak of his ability. But the most interesting parts of Brainwashed are the moments where you feel a heavy sense of dread in his writing. The album’s true standout is “Stuck Inside a Cloud,” a minor key shuffling-panic of a song that finds Harrison reminding himself that only he can understand his thoughts while he’s lost in an emotional fog.

The most interesting parts of Brainwashed are the moments where you feel a heavy sense of dread in his writing.

Similarly, the album ends with the title track, a long, eerily prescient screed on the modern advancements and institutions that are brainwashing us everyday. As the song fades out with sitar, percussion, and a chant from Harrison, it feels like one last plea for recalibration in a world askew. Midway through that final song, Harrison turns the mic over to a woman named Izabela Borzymowska to read a passage from the classic yoga text How to Know God: The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali. In between his grievances on the mind-numbing effects of mobile phones and government propaganda, the passage reads:

The soul does not love, it is love itself

It does not exist, it is existence itself

It does not know, it is knowledge itself

With Brainwashed, George Harrison was able to close the circle on a life spent searching for answers, feeling content in knowing the journey never stops, but is always worth taking. FL