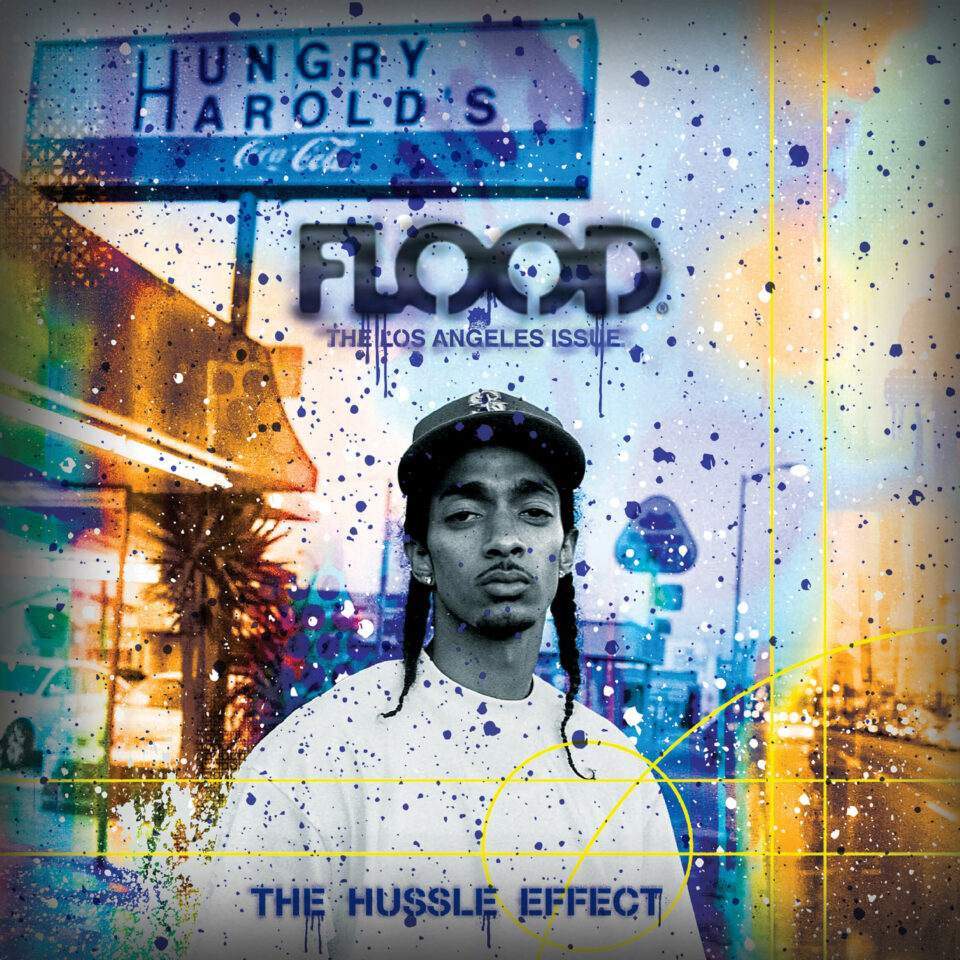

This article appears in FLOOD 12: The Los Angeles Issue. You can purchase this special 232-page print edition celebrating the people, places, music and art of LA here. For a limited time, you can also purchase a signed and numbered art print of the Nipsey Hussle cover by Estevan Oriol, RISK and TAZ here. 50% of proceeds benefit the Neighborhood Nip Foundation.

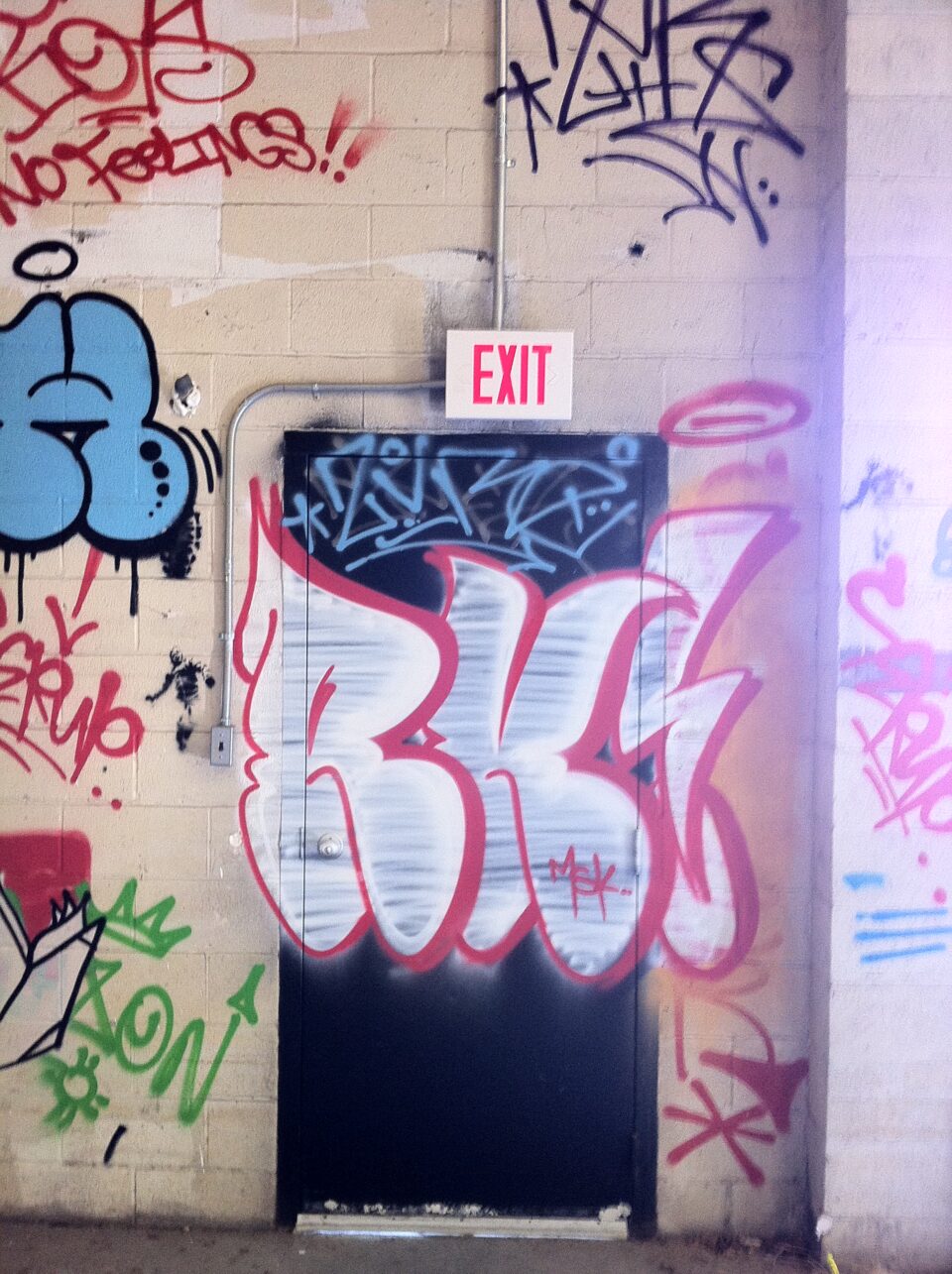

The exterior of Kelly Graval’s estate in Thousand Oaks, CA is rather unremarkable, aside from its cavalcade of tombstones, skeletons, and spiderwebs. Graval—otherwise known as legendary graffiti artist RISK—goes all out for Halloween. Once you enter through the side gate, however, you’re immersed in a creative oasis, a two-plus-acre artist compound with striking visuals in every direction.

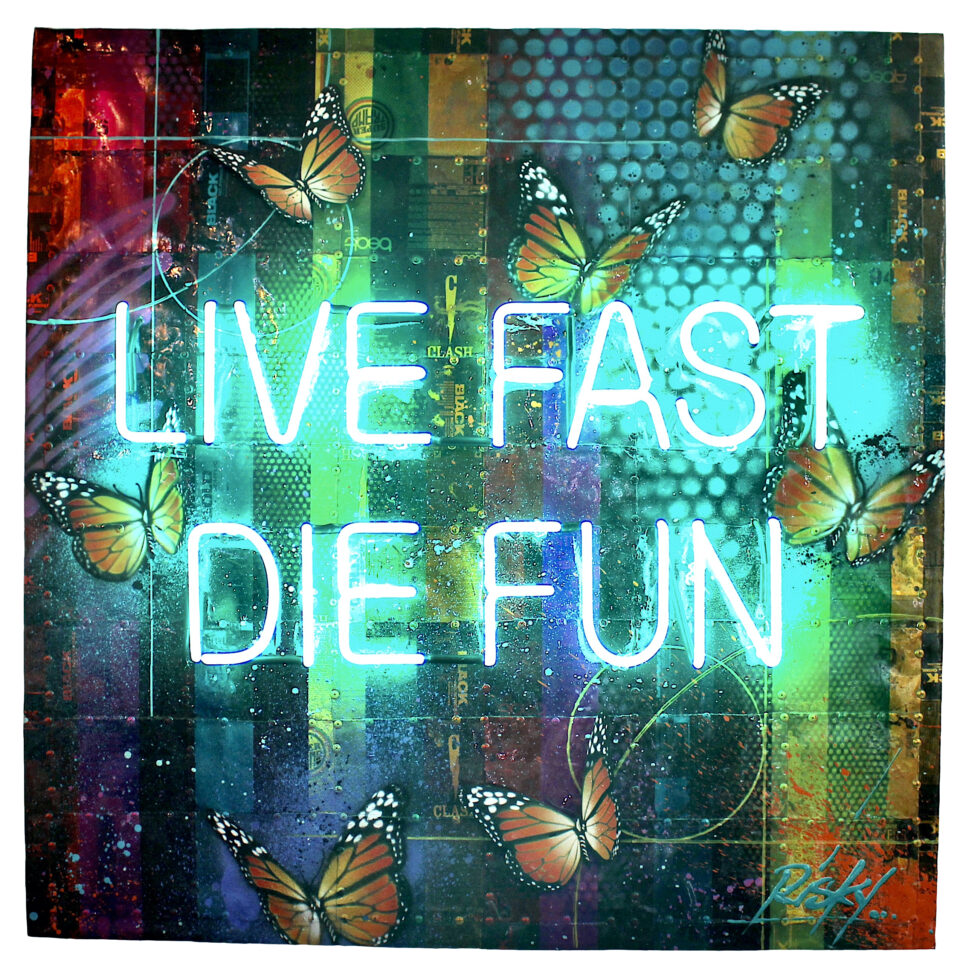

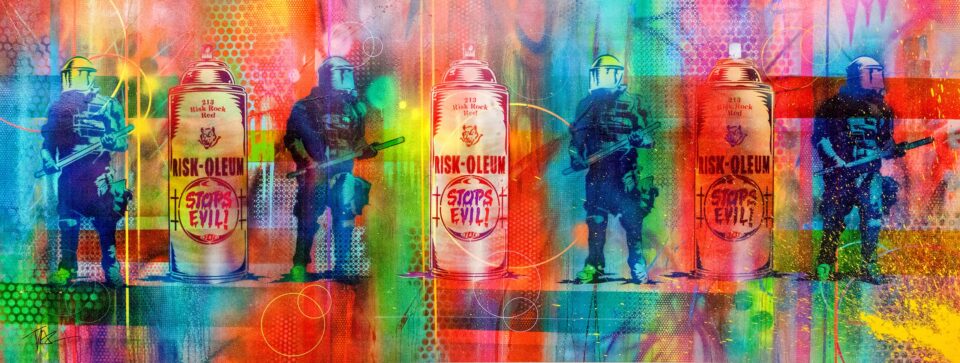

On one side of his expansive property, there’s a large semi-open workspace, with a wall of hundreds of meticulously organized cans of spray paint. His team is busy working on a series of his famous “Alphabet” paintings, cranking out large canvases of each letter for an upcoming exhibit. On the other side, there’s a large shed housing vintage cars, old signs, and works-in-progress sculptures, including large sharks for his “Face Your Fears” series sculpted from hundreds of recycled metal objects.

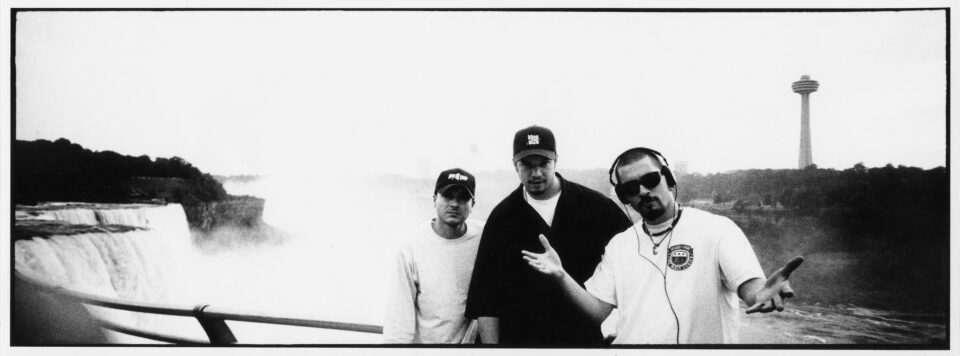

Studio visit with Risk, Estevan Oriol & Jim Evans. Photographed for Flood Mag.

Studio visit with Risk, Estevan Oriol & Jim Evans. Photographed for Flood Mag.

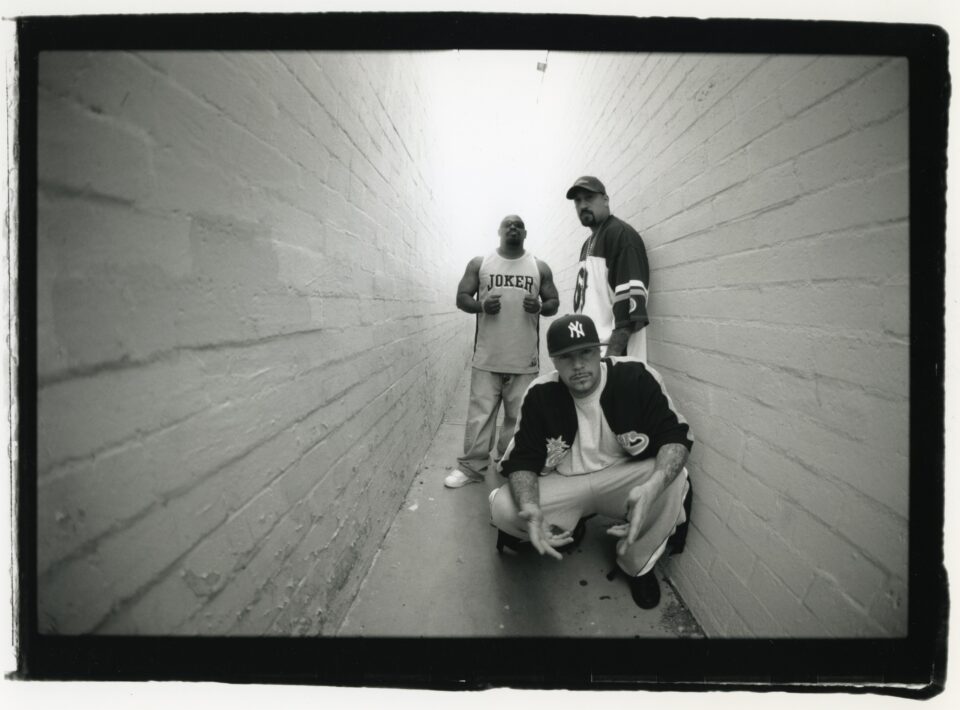

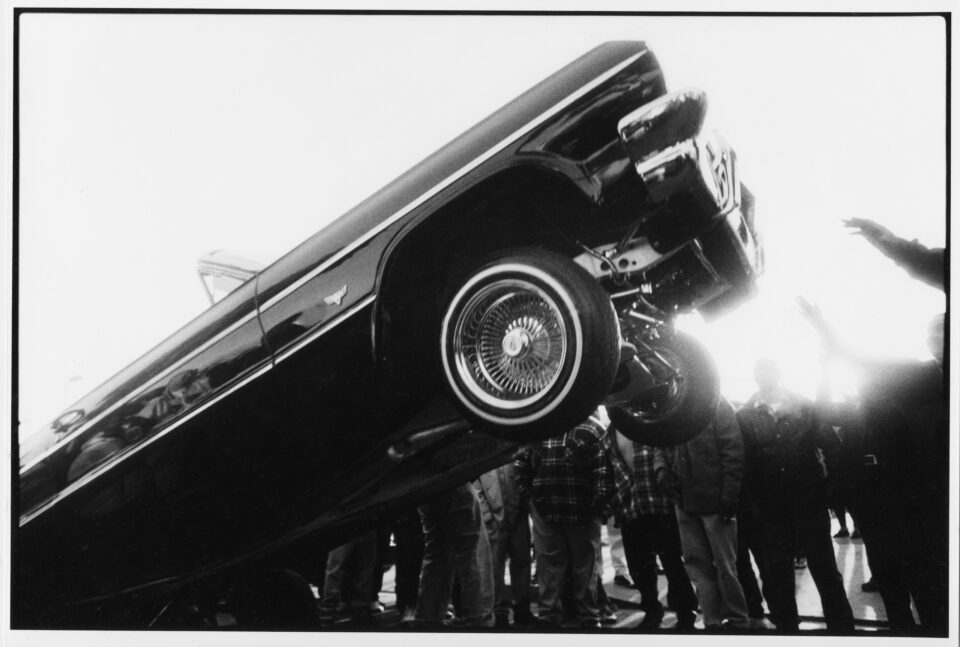

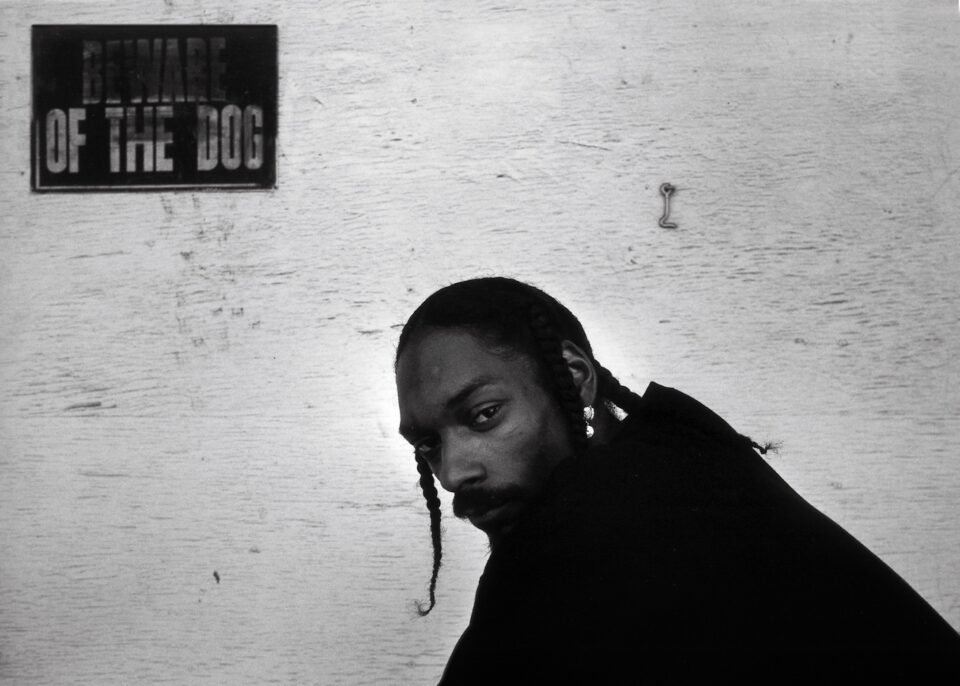

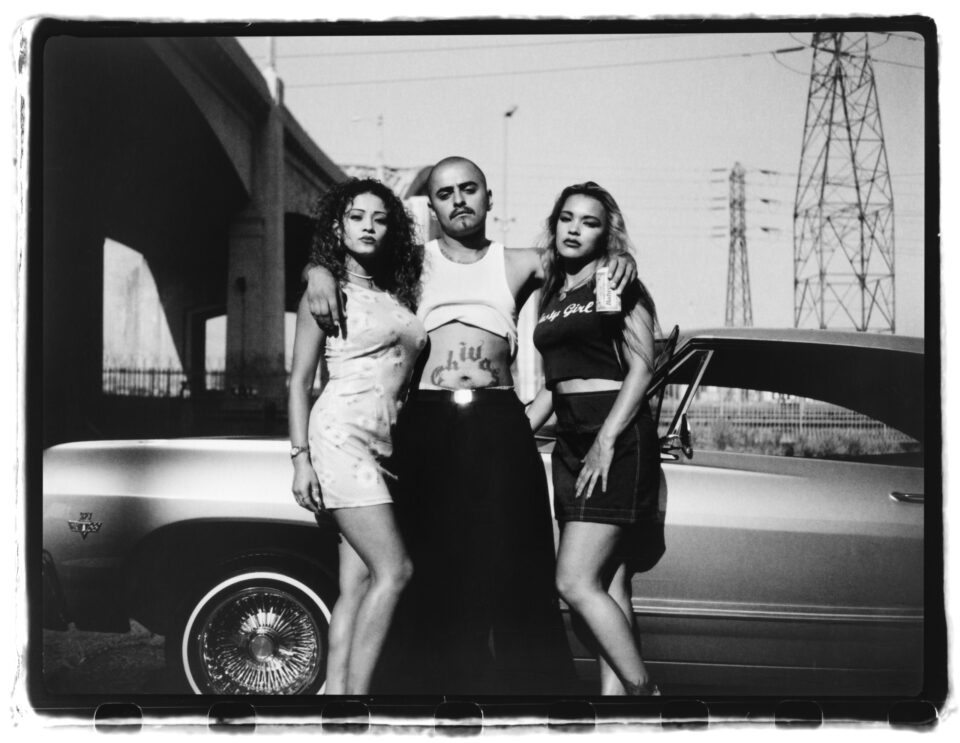

We’re here to meet with RISK, photographer Estevan Oriol, and poster artist Jim Evans a.k.a. TAZ—three artists who have been synonymous with Los Angeles art for several decades. Rising to prominence in the early-’80s, RISK is widely considered one of the founders of the West Coast graffiti art movement and has been instrumental in ushering graffiti and street art into galleries and museums. Oriol first connected with RISK in the late-’80s while working as a bouncer at local clubs. He went on to become tour manager for rap icons Cypress Hill and House of Pain, before establishing himself as one of the preeminent photographers of LA street culture, documenting lowriders and gang lifestyle as well as musicians and celebrities. His story of coming up with tattoo artist Mister Cartoon—his partner in the now-defunct creative agency SA Studios—is detailed in his recent Netflix documentary, LA Originals.

Studio visit with Risk, Estevan Oriol & Jim Evans. Photographed for Flood Mag.

Studio visit with Risk, Estevan Oriol & Jim Evans. Photographed for Flood Mag.

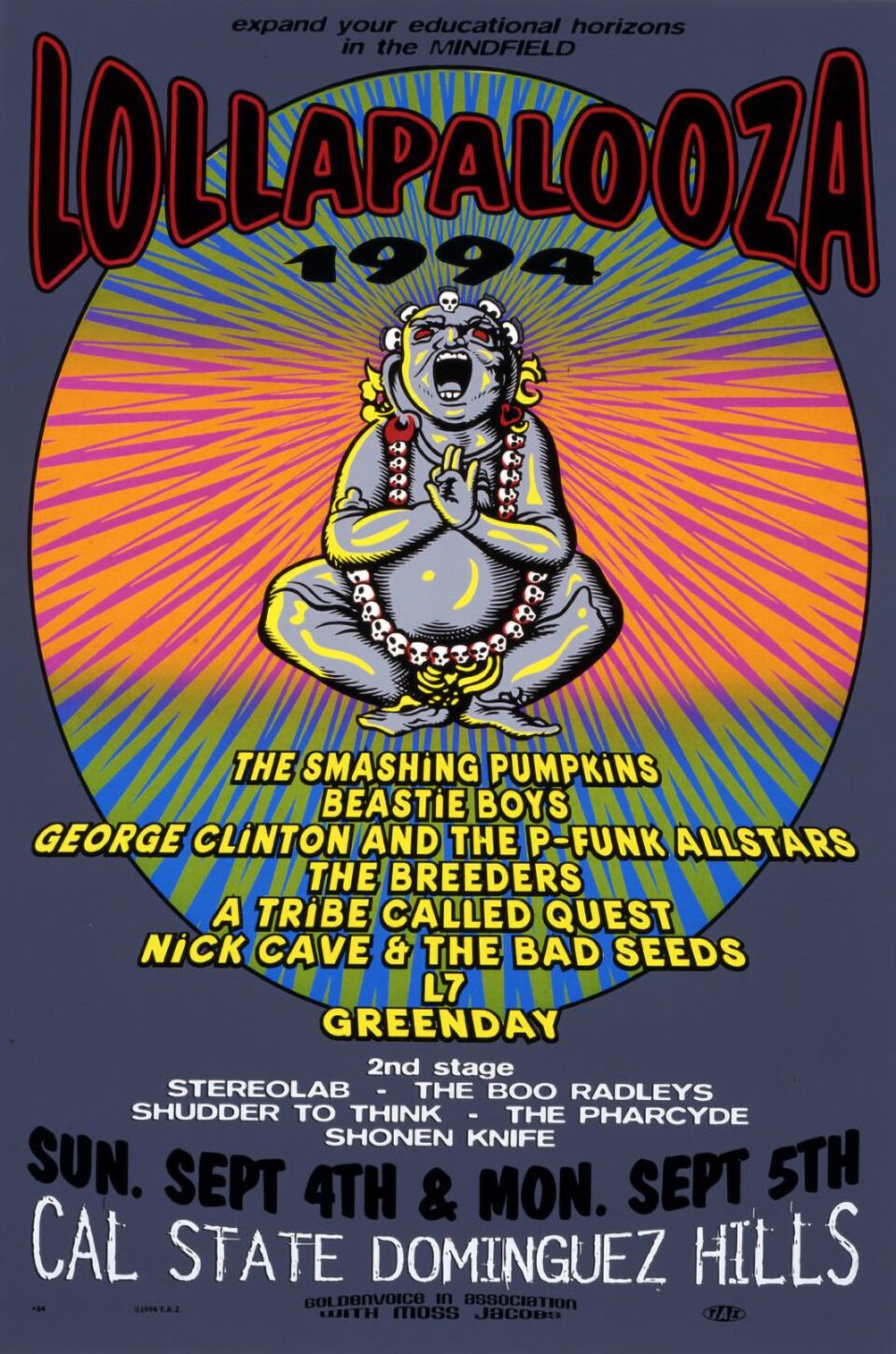

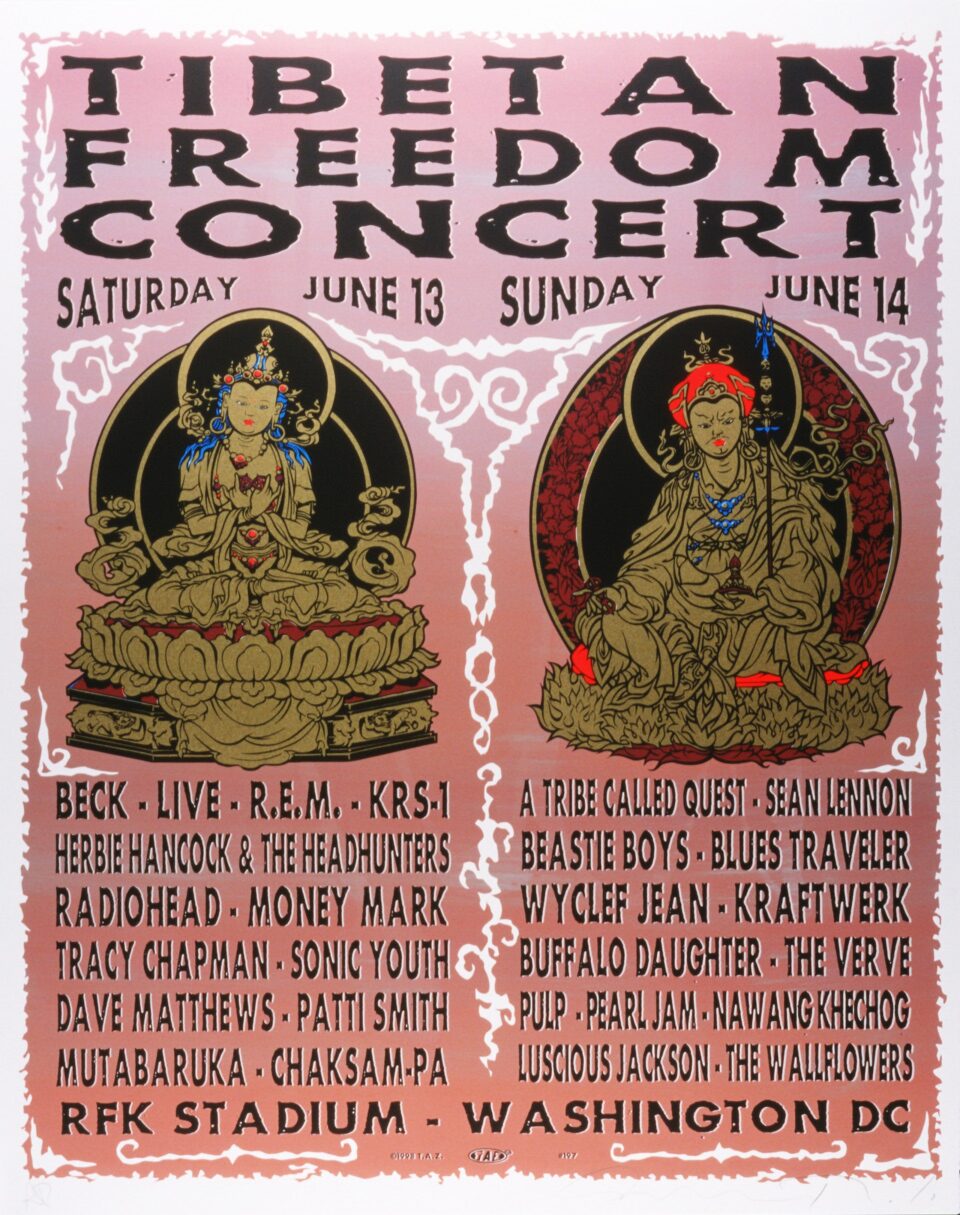

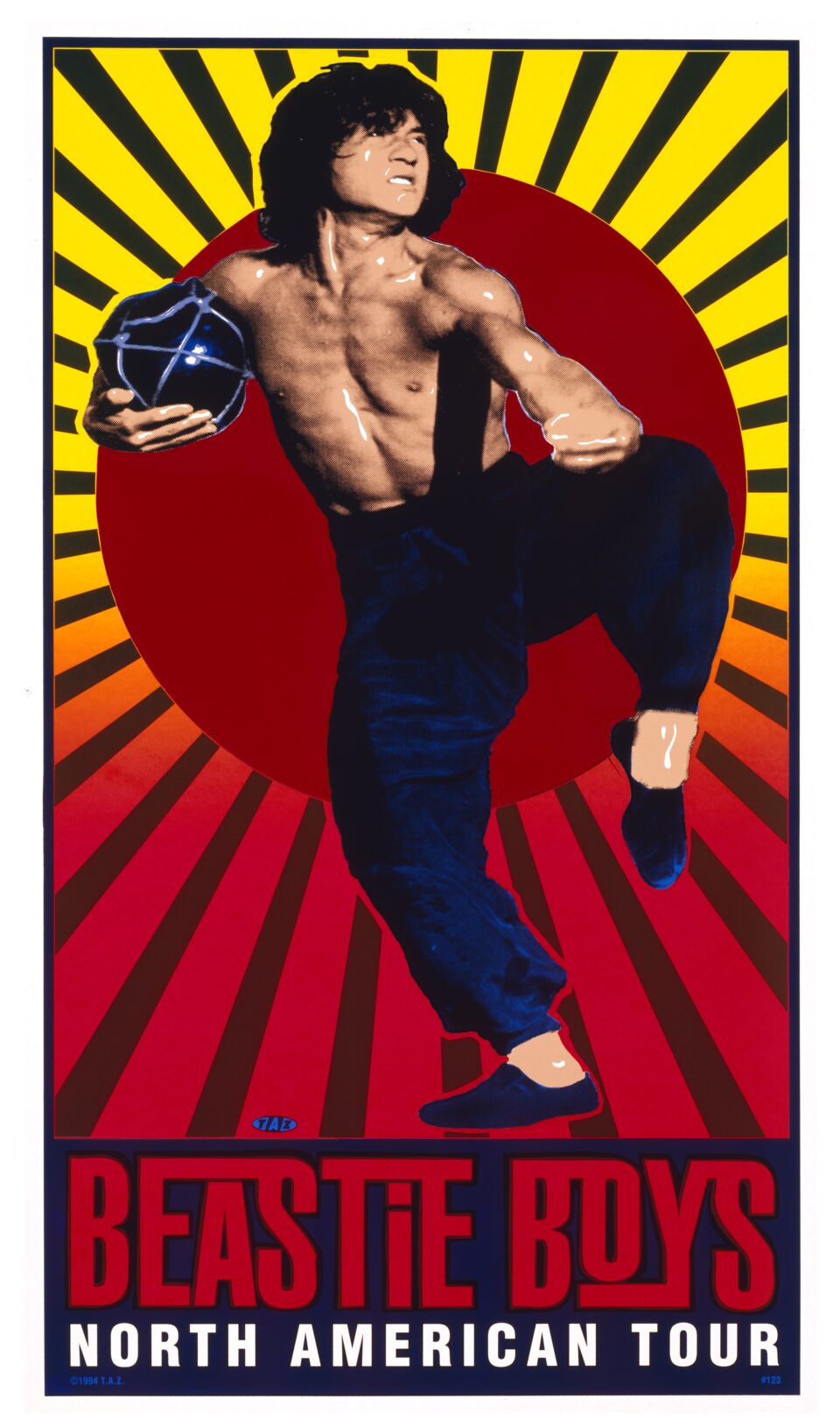

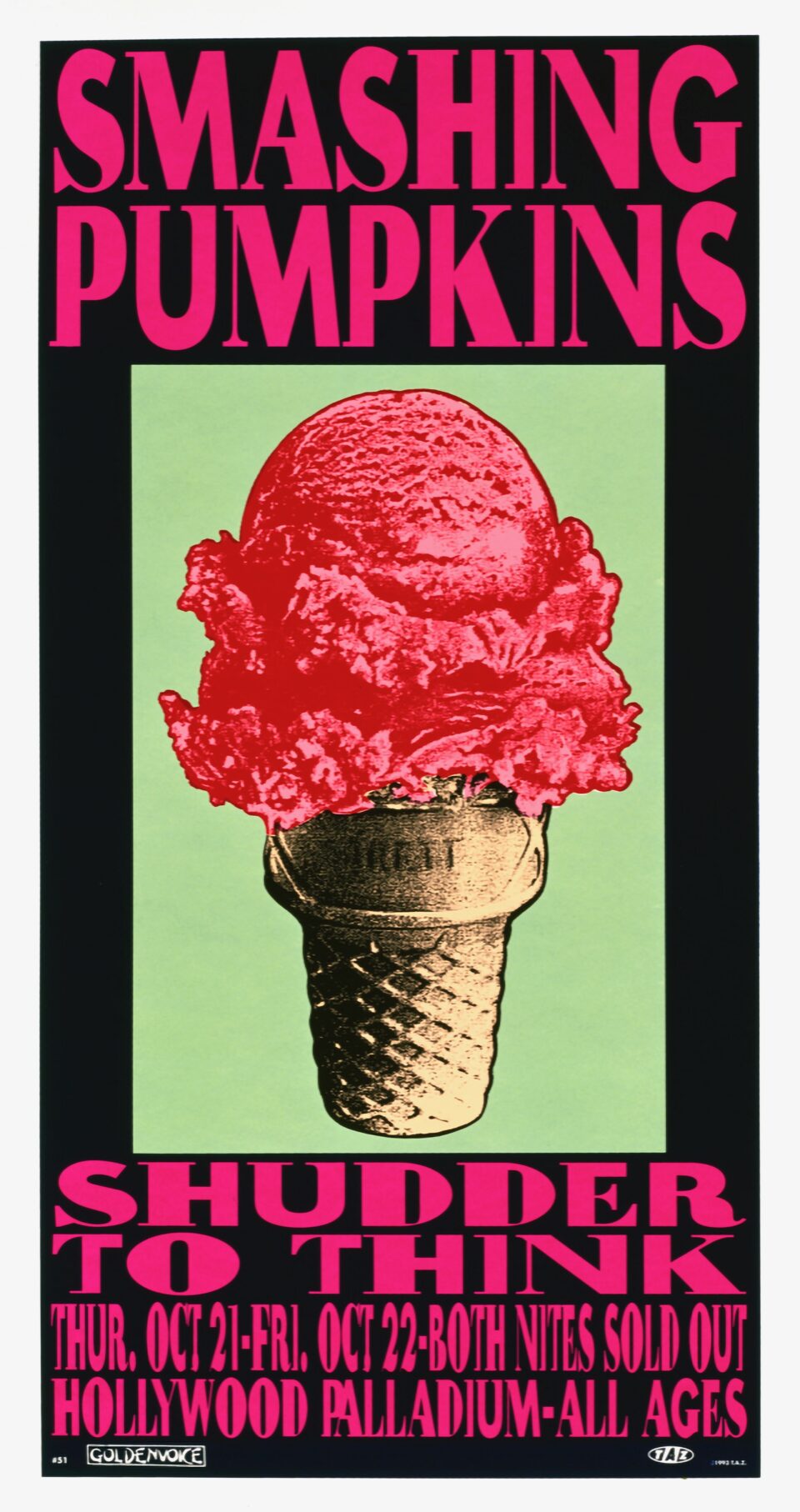

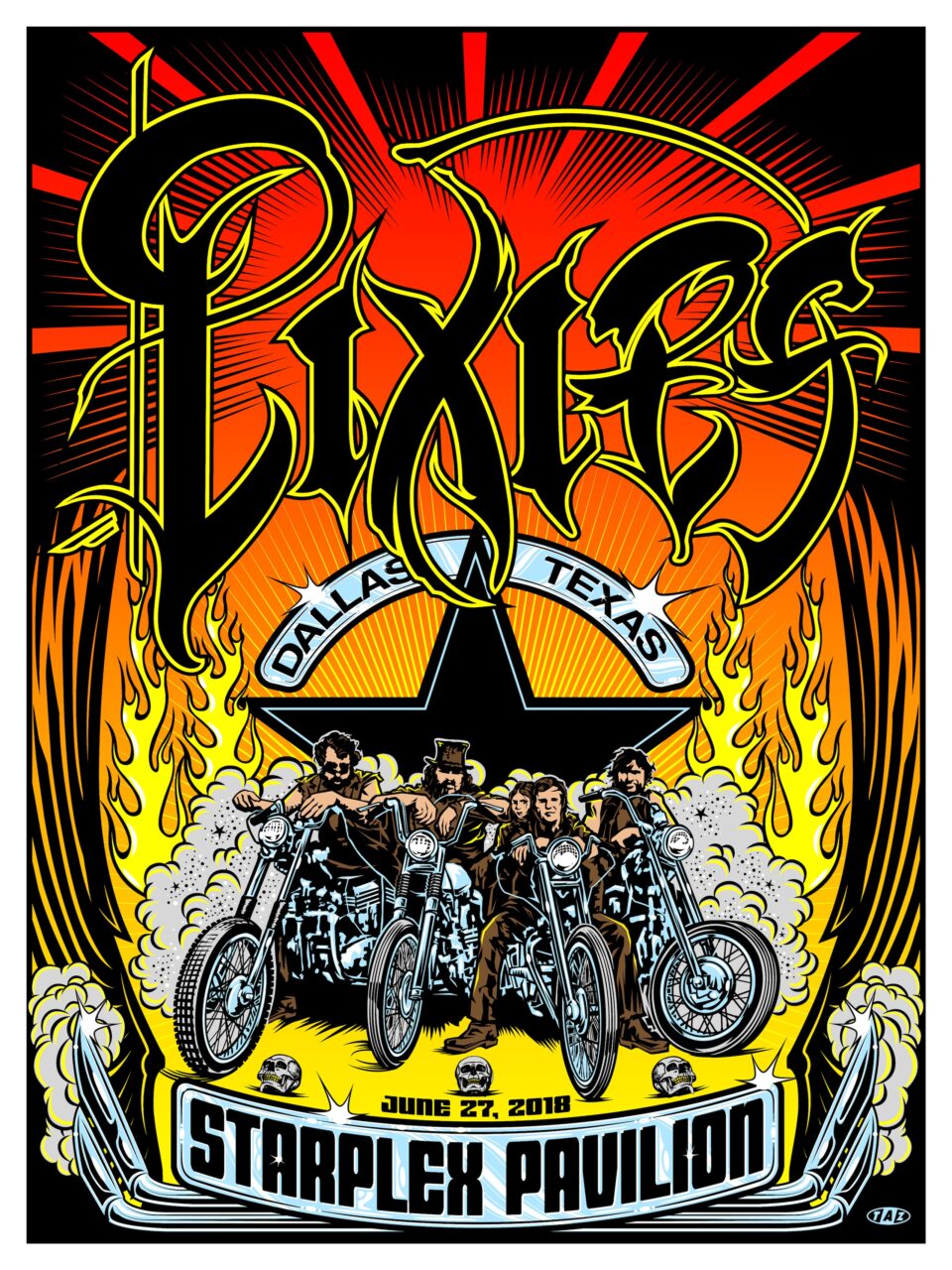

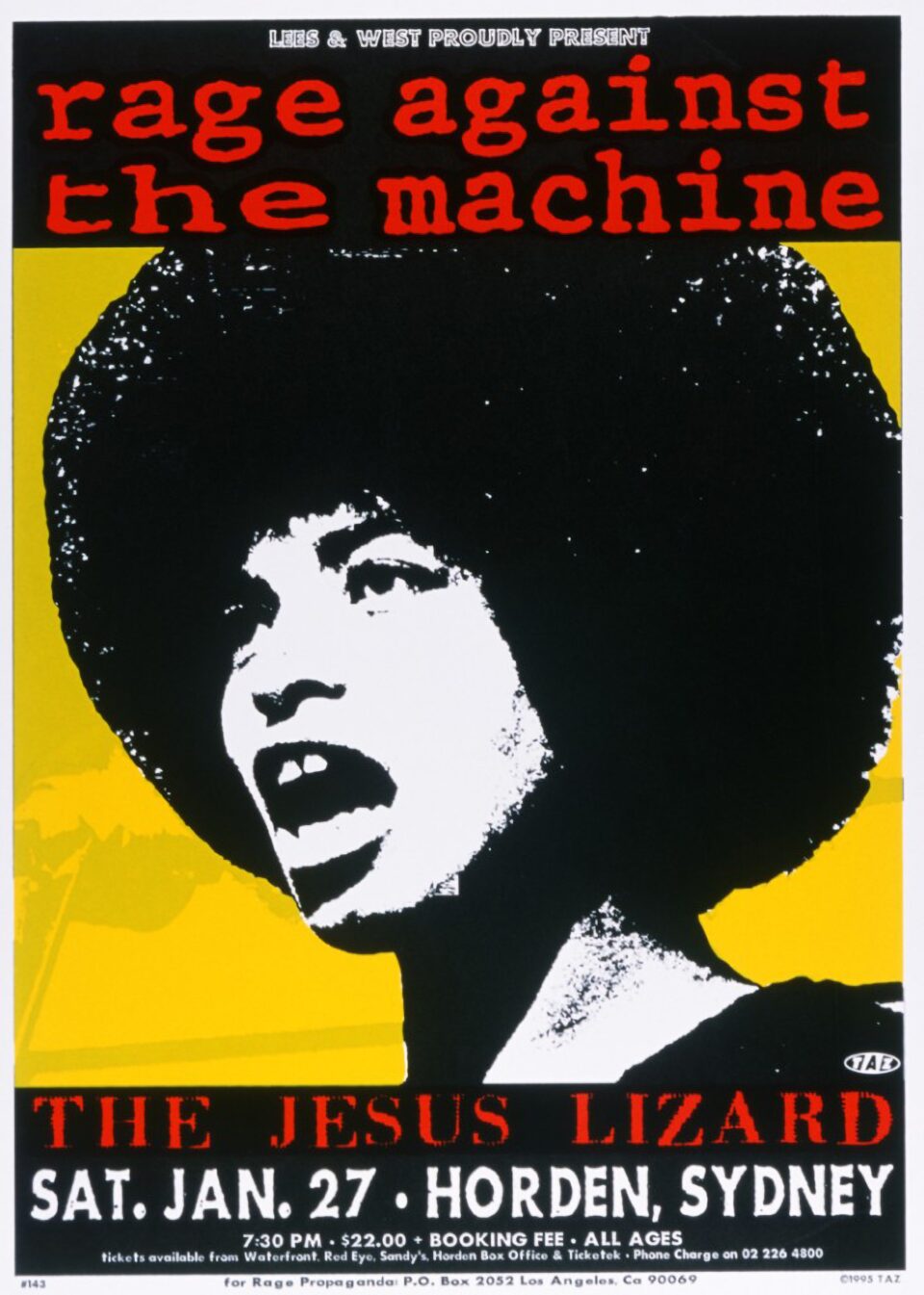

Jim Evans’ work in LA dates back to the early-’70s—when he worked on classic album covers for The Beach Boys, Robbie Krieger, and Neil Young, among others—before creating the TAZ collective in the late-’80s. As TAZ, Evans produced hundreds of concert posters that helped define the look of the alternative rock era for artists including Rage Against the Machine, Beastie Boys, and Beck. A frequent collaborator with RISK, Evans also operates the Division 13 Design Group, producing web campaigns for films ranging from Spider-Man: No Way Home to Space Jam: A New Legacy.

Since Southern California has profoundly impacted each artist’s work—from car and surf culture to their connections to LA rock, punk, and hip-hop—we had to get them together for this special issue to share their stories about creating art in our city.

One connective element with all three of you is the integral role music played in your careers. What are some of your earliest connections to music in Los Angeles, and how did that help shape your career?

RISK: I was raised in New Orleans. My uncle was in a band and he introduced me to rock music at a very, very young age. I was a kid and I’d sit in the room while they practiced, seeing people doing drugs and drinking. I got infatuated with Led Zeppelin, and I just loved rock music. So I came out here and I used to go up to Sunset to the Whisky and Gazzari’s and the Rainbow and all of these places. The beginning of heavy metal glam rock with Mötley Crüe and all that stuff was just starting, so I got to meet a lot of these bands because I’d be out tagging and they’d be out putting out fliers. Living in Hollywood and having a studio there, running around with those people, as we’d grow up together and become successful, we’d feed each other. If they needed an artist they’d call RISK. I just became the graffiti artist for the rock stars. Like Aerosmith and Joe Perry and stuff would call me up, we’d hang out, I’d take them bombing.

It just kind of happened naturally. I ran away when I was 16 or something like that. I lived on couches in Venice Beach and then the punk rock thing was starting. I thought that was super cool because LA was making its own style in graffiti writing. I contribute that to LA being very aggressive with punk rock, whereas New York was hip-hop. If you look at my style it’s very derivative of New York because I grew up with only hip-hop graffiti. I was mimicking the trains, and then the younger generation started getting these sharp lines and these jagged edges and all this stuff. I was like, this has to be the punk rock influence, especially from Venice Beach, because Venice was such a mecca for graffiti at that time. Suicidal Tendencies and all these cliques we were in.

Studio visit with Risk, Estevan Oriol & Jim Evans. Photographed for Flood Mag.

You also did the set designs early in your career for several music videos. Michael Jackson, Ice Cube, Chili Peppers....

RISK: Yeah, I did the MTV Videos Music Awards, Arsenio Hall Show. The Michael Jackson thing was great because when I did that I was in such a bubble. This guy goes, “You’re responsible for all the beautiful artwork?” I was like, “Yeah, I guess so.” And I was like, “Who is that freak?” They were like, “That’s Michael Jackson!” I didn’t realize how much of a genius he was. He’d clear the set and choreograph the whole thing. I hid up in the rafters and I was watching him. He’d jump around the car dancing, doing all this stuff. There’s no choreographer writing that shit out, he just got in there and did it. I was doing that video [“The Way You Make Me Feel”] because I was just trying to get paid. I was like, “Yeah this is gonna be a lot, it’s going to be like $30,000.” They thought I meant $30,000 worth of paint. I had truckloads [of paint] coming in. I think I got every case of Krylon in LA county coming in at that time. I put it in my apartment and just stacked it up. And then I got a check for $30,000! Back then that was a lot of money to me. He had me design three sets: one was New York-style graffiti, one was gang writing, and one was the hybrid of both. He was gonna pick one, but he used them all.

So I started doing set work. At that time I had a studio in Hollywood at Hollywood and Ivar. It was a really dingy room. No water, no power, I’d have to run hoses up the elevator shafts and extension cords. I was not supposed to be there at night and I’d hide. I’d go around Hollywood and wherever they were filming and doing graffiti, I’d be like, “That’s fake, let me do it.” I’d do it just for craft services, just to eat, you know? Then they started calling me, I’d get like $100 a day, which was great. And then it rolled into all of this other stuff.

Studio visit with Risk, Estevan Oriol & Jim Evans. Photographed for Flood Mag.

Estevan, you were coming up in LA around this same period. How was music instrumental in shaping your career?

Estevan Oriol: I was always hustling doing two or three jobs because my mom was disabled and my dad was in San Diego. I was doing construction during the day because that’s what most people did that I knew, and then I’d work the doors at clubs at night. That’s how I met everybody. They had to come through me to get into the club. I met Muggs [from Cypress Hill] at the King King on 6th and La Brea. We started hanging out and going to all these clubs, that was like in the late-’80s, and he took me down to Cypress Ave block and I met Sen [Dog] and B-Real [from Cypress Hill]. So I’d always tell them, “Come to the clubs, I got you,” and we all became cool.

Cypress Hill / Photo by Estevan Oriol

Then Muggs in ’92 said, “I got a job for you. It’s with these white boy rappers.” I was like “Fuck, what’s this gonna be like?” He goes, “It’s Everlast! I want you to tour-manage his new group called House of Pain. Just make sure they show up to all their interviews on time, to their shows, just look out for them.” So I went on tour with them and that summer they blew up. “Jump Around” became one of the biggest hits ever. I tour managed them, ’92, ’93, ’94. And then they decided to break up. I called the homies from Cypress, “Thank you for this opportunity, I traveled the world, I made a little bit of money, I was able to finish my lowrider. Thank you very much, I’m going back to construction and working the clubs.” They’re like, “Nah, don’t even trip. The guy who was our tour manager just fucked up, you got a job with us now.” My first job was at Woodstock ’94. I did good on that one and ended up rolling with them until 2005, when they quit touring.

House of Pain

My dad gave me a camera, and he was telling me, “You should document your life. One minute you’re on the road traveling with these guys, living the rockstar life. The next minute you’re back home, building your lowrider, kicking it with your homies in your lowrider club in East LA.” I wasn’t really into it. I thought photographers were kind of corny and tacky, even though my dad did photos. What I knew about photography, it was mostly fashion or paparazzi or tourists or people that shot products. And I was like, “I’m none of those guys. I don’t want to be walking around with a camera with a strap around my neck.” I thought that looked crazy, you know? So I didn’t really fuck with it that much. Then I started breaking it out, little by little.

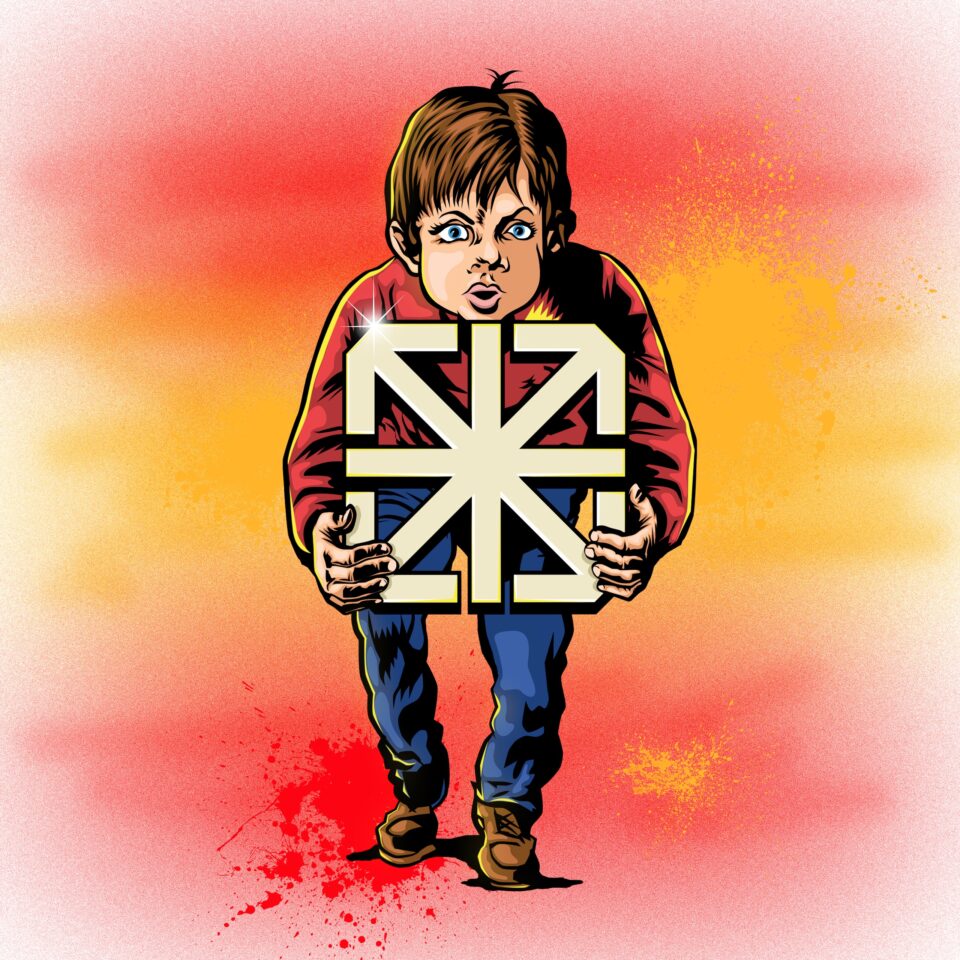

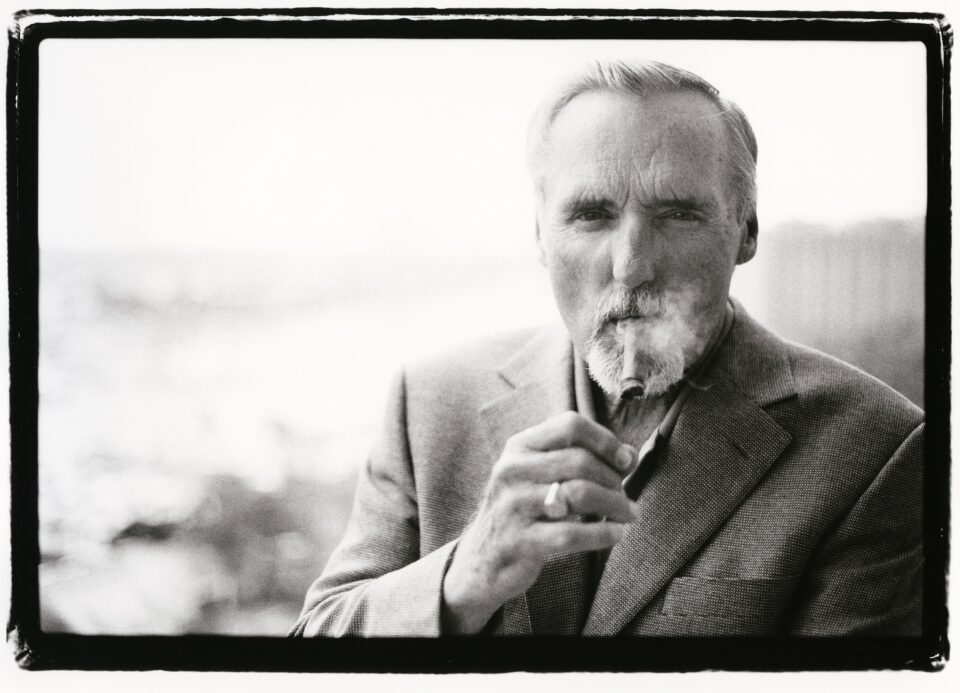

Jim Evans aka TAZ

Jim, coming up in the ’60s and ‘70s, you had an entirely different experience than Estevan and Risk did, but music was also central to your development as an artist...

Jim Evans: These guys are kind of lucky, ’cause youth culture actually existed when they came up. I was raised in the death culture of the ’50s, it was the backwash of World War II. Everybody’s father had been in the war, everyone had somebody that had died. So for me, music was really an escape. Every teenager wanted to be in a band, wanted to be a singer, wanted to be a rock ’n’ roll star. I actually started a band in high school. I was a scribbler who loved music, but at the same time I didn’t really think that art was very cool. I didn’t really know where to go with it.

I was the guy [in the band] that always came up with ideas for branding. I was like, “No, man, we all gotta do this, we gotta do that.” They were like, “Oh, fuck you.” So I started doing posters and drumheads for other bands. One thing led to another, and I ended up going to art school in Los Angeles. At that time, I’d seen enough where music and art were completely combined, because you had the whole San Francisco scene, you had a worldwide explosion of psychedelic culture. Like when I saw Cream at the Whisky, they came out and their guitars were all painted and they were dressed in painted clothes. The band was art, you know?

For me, in my young mind, art is suddenly cool. I met [iconic ’60s comic and poster artist] Rick Griffin and a couple of other people and they introduced me to more musicians. I went to his studio and he’s working on a piece of work for The Beatles. I’m like 10 years younger than him, he’s already like a fucking complete god to me, I’m thinking like, “Holy shit man, I’ve died and gone to heaven.” He started giving me album covers [to design]. I was like 19, 20 years old. And I got Alice Coltrane, John Coltrane’s wife, as my first album cover. Then I was kind of on my way. I think since I’d been in a rock band, I could talk to rock musicians. I knew what they were thinking. So I could translate that into album covers.

Estevan, going back to when your father gave you your first camera, when did you realize you had that skill and start taking photography seriously?

Estevan: I thought I was gonna put it down and not touch it. When your parents tell you something is cool, you’re like, “Yeah, OK, great. Why would I take this camera to a place like a concert or a fucking skateboard park? I’ll look like a weirdo with this big old fucking thing.” So I missed out on pictures of all of the Dogtown and Z-Boys ’cause I didn't think it was cool to take that [camera] skateboarding with me. I didn’t take a camera to all the cool shows I went to. At a certain point, I started doing it more and more. When I’d see the pictures come back and I’d see other people that were taking pictures, I realized that my photos were a little bit different than theirs. Theirs were always fucking twisted or out of focus or the flash blew out the person’s face so much that you couldn’t see them. I would look through my shit and be like, “Wow, I got a lot better pictures than they did.”

The only place that I knew to take my film to was a place called Focus Photo on La Brea, ’cause that’s where my dad used to go. At that time they were doing Helmut Newton and all of the bigshots in LA, so I knew I was in the right place. I would just go there and drop off a roll of film, get a contact sheet made, and I would jam. It came to the point where I had two milk crates full of contact sheets and the negatives in the trunk of my car. [The lady there] was like, “How come you never make any prints?” I was like, “For what? What do I need a big fucking print for? I just take pictures, I’m not going to do anything with these big pictures of people I don’t really know.”

I’d go to this one-hour photo lab at the Beverly Center and they would make these little one-hour photos, you know, the whole set. I would show the homies like, “I got the pictures back from the tour.” They were like, “Fuck, you take good pictures!” I started hearing that enough, and then the lady [at Focus Photo] told me, “How about if I blow up your prints and we put them here in the lobby?” Which was what she did with all of the other big-time photographers. “And if you sell them, I’ll give you the money.” I was like, “Yeah, OK, whatever.” She made 11 16” x 20” photos and out of the 11 photos, eight of them sold. She said she’d never sold that many photos ever from one person. She was like, “People usually come here and buy musician photos and celebrities. You just have normal people doing regular shit, and people bought the fuck out of it.”

She had an eye for your talent before you even realized it.

Estevan: The cool thing was that I listened to her. She told me, “You have an eye for good pictures, and we just proved it. You should take it more seriously.” I was still not all the way there yet in my head. But that was a real point where I started to take it more seriously.

Kelly, when you first came out here from New Orleans, what part of town did you live in?

RISK: My dad moved around a lot. I went to like two schools a year. I got to [University] High in half of tenth grade and eleventh and twelfth and that was the longest stint I did in school. My dad was a drug dealer—not like a major drug dealer—and he laundered money, and he learned how to take a lot of these guys’ money and put it into commodities. And he started doing really well. My dad was a really smart guy, he took the bar exam, graduated law school. My mom was a teacher, and she couldn’t control me. I stole an XR75 dirt bike from the Honda showroom. We had truant officers that would try to get you back to school. Because my mom was a teacher, they were like, “This looks really bad. You have to get your kid to go to school.” So I just quit school in seventh grade. She was like, “Let’s go visit your dad.” He was living near Lake Tahoe at the time. We got on a plane and landed in Reno, and it was the first time I ever saw snow. She was like, “Oh, you like that? Good, ’cause you live here now.” My dad’s at the airport—he was a big dude—he’s like, “You think you’re badass, huh? Well, I got a surprise for you.” So we went to Lake Tahoe where he lived and he hired a teacher to take me from class to class and live with us to make sure I didn’t ditch.

From there, I went to Manhattan Beach and then Palos Verdes, and a couple places in between. The whole thing with my dad was that every time I moved, he wanted me in the best school districts. When we got to West LA, I lived up on Beverly Glen, and I went to Uni High and I had all this freedom.I had a Mazda 626 and I would go all over the city. I would go down to the Hazard Projects and paint, I’d go to Radiotron [an infamous hip-hop venue and youth center near MacArthur Park], all these places. I spent most of my time on Venice Beach. That’s where all my graffiti really took off, because I was a loner, kind of. I would just sit out there every night and paint. I became friends with all the dudes in Venice and they took care of me. Uni High was in West LA, but I spent most of my time in Venice, and maybe the first summer out of high school I got my studio in Hollywood. I did a lot of graffiti in East LA. I think I got shot in the Valley and stabbed in East LA.

What were you doing when you got shot?

RISK: Graffiti. I was doing the Budweiser Train Yard. I was painting over there a lot. I got stabbed jumping a fence in Downtown. I had a studio downtown, you guys remember that place? That place was crazy. I had a 45-foot bar in there. Pool table. We’d shoot shotguns out the back window. But my early graffiti career was Sepulveda and Pico, the West Coast Tracks, and then most of my time in Venice Beach when I was young.

I’ve read that your high school was the first place you started tagging?

RISK: Yeah, I was a problem kid, I didn't have a lot of friends, and I just got lost in the art. I would just sit and draw on my desk or my books. I dont even know how the fuck I got away with it. The whole desk would be covered with just colors and shit. This kid was next to me like, “What are you doing? What do you write?” I was like, “I don’t really write, I draw pictures.” And he’s like, “No, what do you write?” I’m like, “Motherfucker, I don't write, I draw pictures! Are you stupid?” And he’s like, “No, that's a subculture, it’s called writing, it’s called graffiti, tag.” And he goes, “So I guess you are technically Surf,” ’cause I used to write the word “surf” with these waves and shit. I was like, “Oh yeah, I guess it is, I do that shit.”

That day I went and stole two cans of red and two cans of white spray paint, and went back to Uni High, and I sat outside just staring at the school waiting for it to get dark. It was dusk, I jumped the fence, and I did this big fucking terrible piece that said “Surf.” I remember I was so disappointed. But the next day there was hundreds of kids around it. They were like, “That shit’s fucking cool.” I’m like, “That’s cool?!” They're like “Yeah!” ’cause all they had was gang writing before. “Oh, OK, let me keep trying!” The school was a big campus and they couldn’t catch us—we’d get up on the roof, and then I started thinking I’m going to do the rooftops so they can’t buff it. And then they started buffing it! Then I broke into the school and painted the lockers. They didn’t know how to buff the lockers, ’cause it was metal. The janitors were like, “Hey, you wanna see someone’s legs get broke? I’ll give you $200 if you tell me who did this.” I’m like, “Oh shit!” So yeah, I painted my high school probably every fucking night. It was ridiculous.

Studio visit with Risk, Estevan Oriol & Jim Evans. Photographed for Flood Mag.

They never knew it was you?!

RISK: I got busted, they arrested me. I changed my [tag] three times. I went from Surf to Cajun to Isrock to Riskrock to RISK. I was smart, ’cause they’d call me to the office and check my books, and I’d have fake tags in my books. They’d be like, “I know you are RISK.” And I’d be like, “I wish I was RISK! That dude is up!” I’d write Cajun. I’d be like, “Ah, you got me, it says right there ‘Cajun.’”

You never got kicked out of the school?

RISK: Yeah, I got kicked out. I got reinstated. Our teachers were like, “You can’t do that, he’s the first kid in our school that’s going to get the National Scholastic Art Award, we’ve got scholarships for him.” So last minute they got me back in to walk and graduate. I was very lucky. I got kicked out of USC for the same shit, and my art teachers got me back in. They kicked me out because I said, “Can I go paint on the roof?” And they said, “Yeah.” So I did this mural on the roof. The problem was the dean came up and said, “Oh, this is beautiful, what did you do it with?” I said “spray paint.” She said something like, “That’s like anarchy. We gotta paint over this.” I said, ”Eat a bag of dicks” and that was it, I was out. And then they got me reinstated with scholarships to finish.

Were you aware of any other graffiti artists in LA at this time?

RISK So by the time I was at USC, we had Dream—rest in peace—Cartoon, RIVAL—rest in peace—Power, we had a pretty solid crew of dudes that were well-known. When I first started doing graffiti there was like no one. There were some dudes from New York doing it. I went and found them and met them at Radiotron. I remember when we had like 12 dudes in LA doing graffiti and I thought that was a lot. In the blink of an eye, it was like 12,000. Now, I’m pretty confident every fucking kid in LA has tagged at one time in their life.

I understand you also met Keith Haring at a young age?

RISK: Yeah, I met Keith Haring at ArtCenter in Pasadena. He signed my jacket and I was going to do a mural with him. He got sick and never got to do the mural. Funny thing about that, I was like, “This is what I want. I want to do this. I want to travel around the world and have people lined up for me to sign shit and meet cool people and artists.” Years later, ArtCenter called me, and let me do the first outdoor mural on the campus. [Haring] did the first indoor mural, and I got to do the first outdoor mural. It felt really good. That whole thing was what launched me in the fine art thing.

At what point did you realize you wanted to help legitimize graffiti art?

RISK: I definitely set out to make graffiti a household name. I wanted to make graffiti an art genre. I didn't say the word “graffiti” for years. That was a negative connotation. Graffiti means applying medium to the surface. I was drawing pictures and doing art and wasn't just applying medium to the surface, necessarily. I never wanted to be a graffiti artist, I just wanted to be an artist.

Jim, we talked a bit about your early years, but let’s get to the period when you created the moniker TAZ.

Jim: I was a professional artist for a long time. My career went so quickly between 1970 and 1980, I did so many things that I was really pretty burned out. When I met [artist/printmaker] Richard Duardo, he brought a whole different sensibility ’cause he was doing silkscreen. It’s sort of like the way Kelly works, he just attacks the surface, and I’m so precise. He’d throw colors all over the place, pick stupid colors that didn’t really work with one another. I began to see how you could construct art randomly and at the same time bring a certain precision to it. We came together as a collaborative band, in a way. He brought the chaos, and I brought the precision side of it. I saw the light there, I didn’t want to be the illustrator doing these really perfect illustrations with airbrush.

So I went away from that, went into silkscreening, and then when the economy collapsed in 1988, a lot of the stuff we were doing fell apart, but I had a silkscreen studio. So I decided to reinvent myself as a collaborative entity, where I would work with Rolo [Castillo], who was a silkscreener, and my son Gibran, who did design work on the computer, ’cause computers were starting to come into play, and basically I would do the drawings. I would just hand them to Gibran, he would put some lettering on it, and Rolo would do the color work.

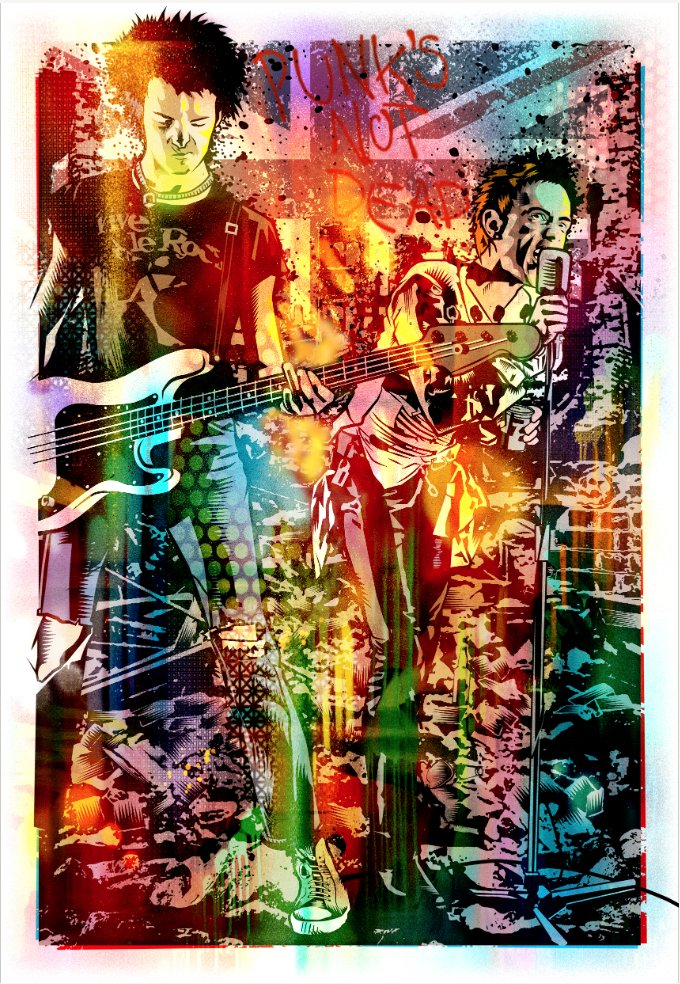

Rolo was born and raised in Tijuana. He brought what I’d call a Tijuana sense of color, which fascinated me as a kid when I’d go to Tijuana. I’d see these taxi cabs...people would write the names of their taxi cab companies with perfectly dimensional Old English with all kinds of highlights. I’d see it driving by and go, “Fucking shit, what is that? Who does that?” It was completely unhinged in a sense I hadn’t seen before. So I brought a lot of that when I started working on the TAZ posters. I ran back to my underground comic origins ’cause I realized I didn’t need to be sophisticated anymore. I just needed to go back to my scribbling stuff. Hot rods, skulls, surfing, really anything you could bottle up in pop culture, put some great colors on it, and actually really worked for these alternative rock posters. I really wanted to do this experiment, like, “How weird can I get with these things?” And it turned out I can get completely weird.

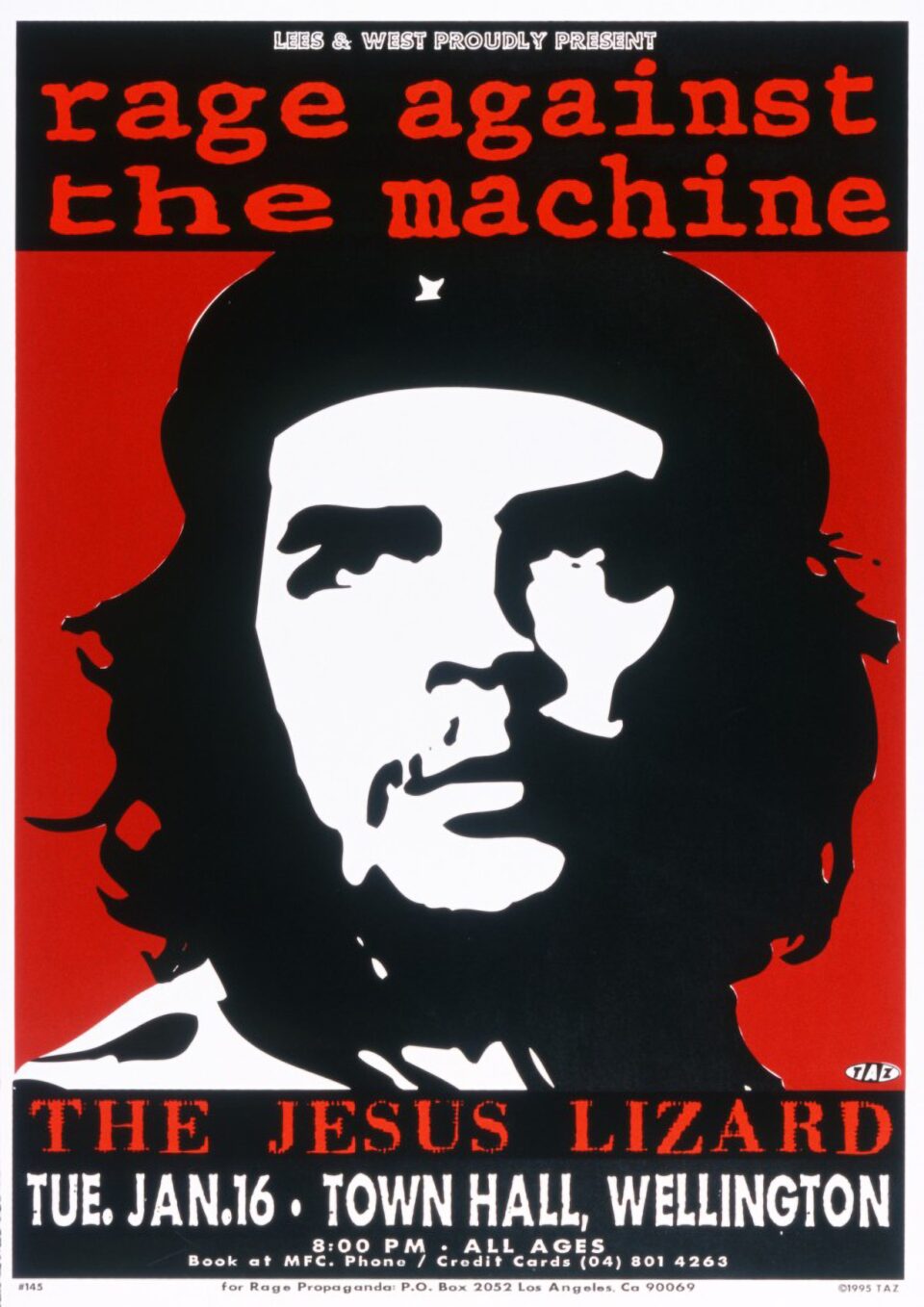

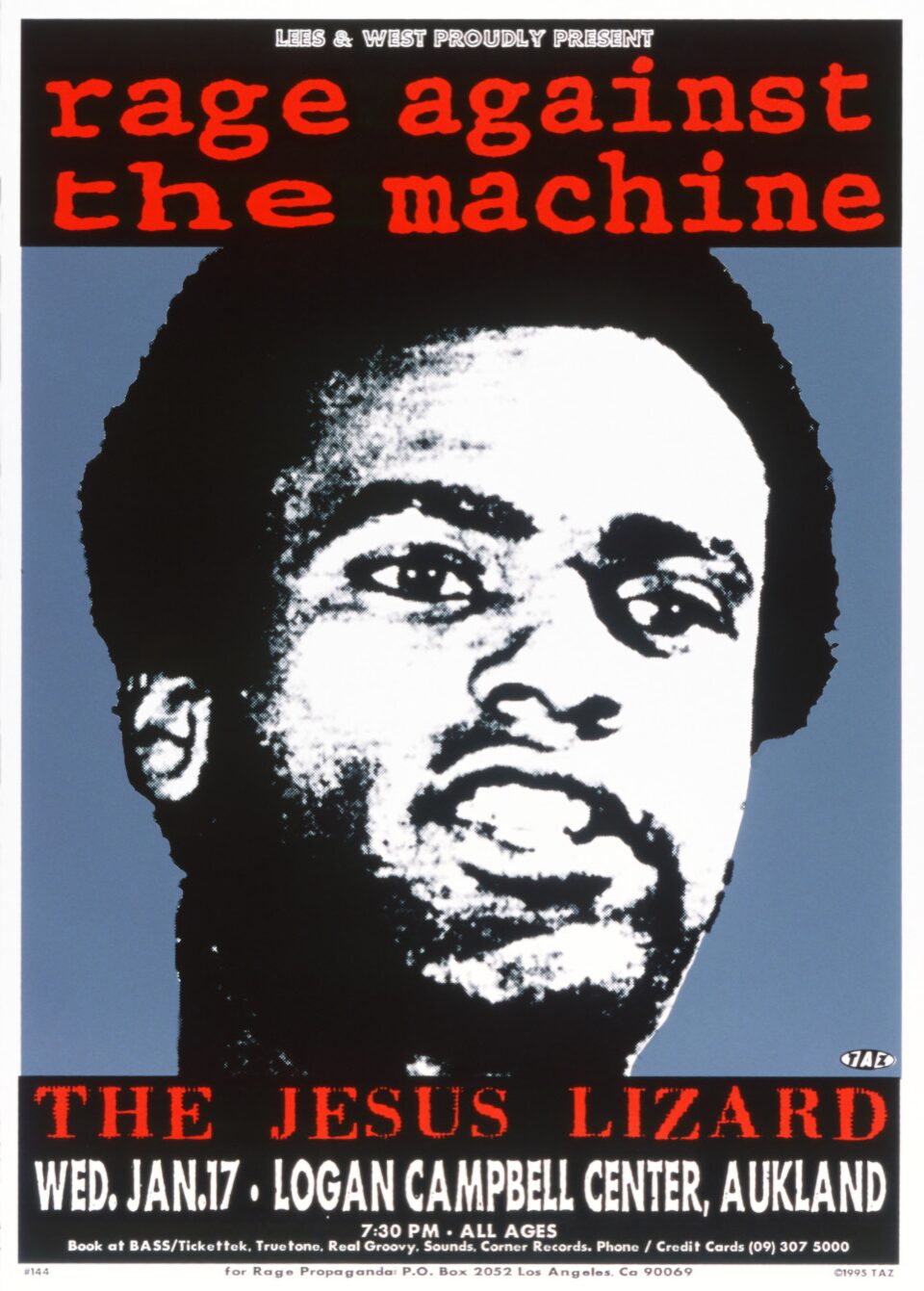

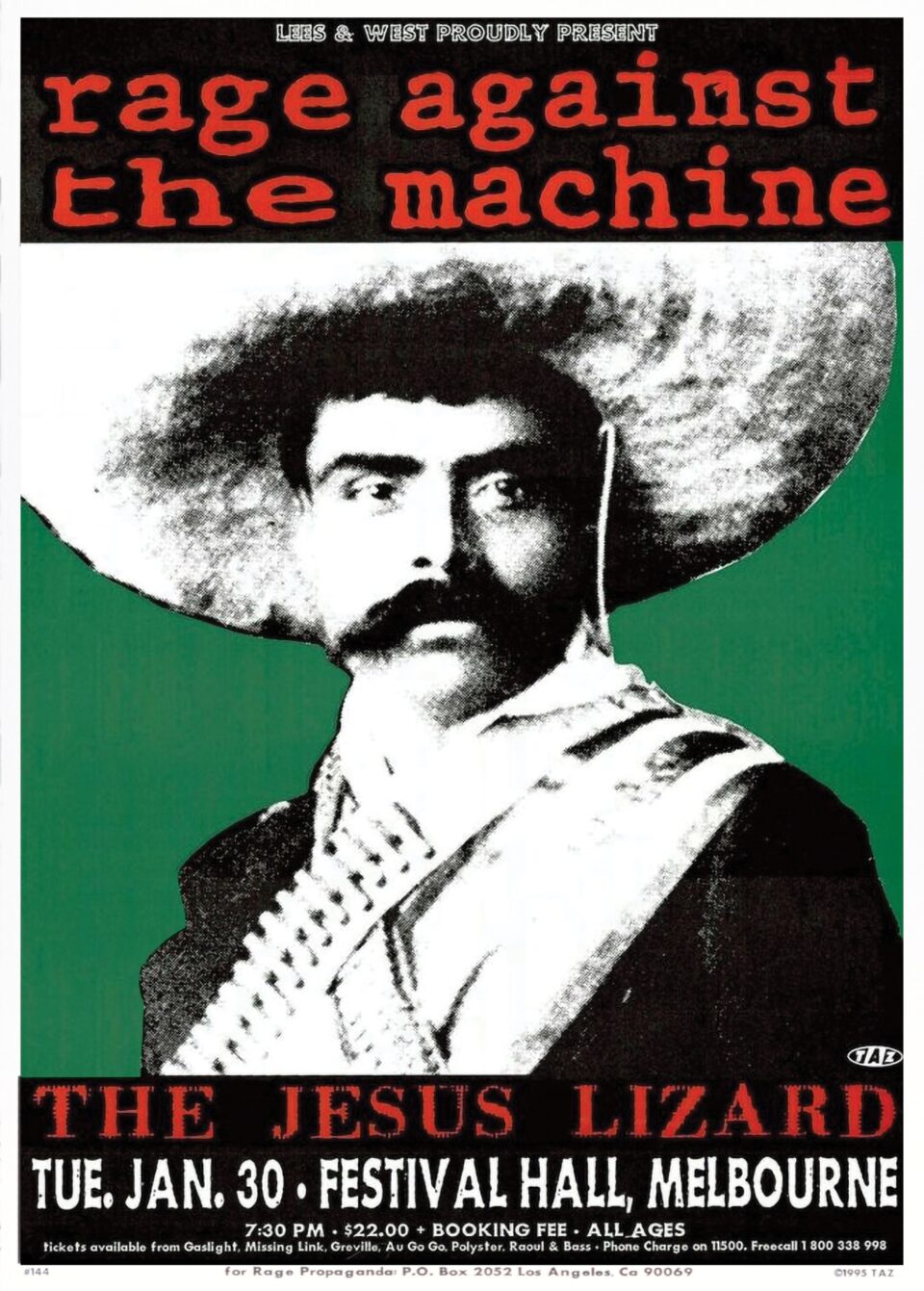

So many of the posters you were doing as TAZ—like the Rage Against the Machine propaganda series—have been imitated by others for years. How did the Rage posters come together?

Jim: It was a simpler time. Zack [de la Rocha] said he was going on a tour in New Zealand and Australia and he wanted major revolutionary figures to be on the posters. He wanted Angela Davis, Che Guevara, and things like that. At that time, I couldn't just go online and steal the images. I actually went to the communist bookstore downtown and bought a bunch of magazines, Xeroxed them, and did them. I used propaganda techniques, like I trimmed everything real tightly, brought everything up really close, I used bold letters.

Basically, my idea for creating a good poster was that you could put it on a telephone pole and someone could drive by and they would see the name of the band, the place they were playing, and if they saw the picture that would be cool, but at the same time they would know Rage Against the Machine was playing somewhere in New Zealand on that night. The three things that were most important were who is the band, where are they playing, and what do they have to say. I think that most of the TAZ posters were like that. Some of them toward the end—like with the Tibetan Freedom Concert—I got more involved with rendering the Buddhist figures out and stuff like that, but that was just ego, and showing that I could really render.

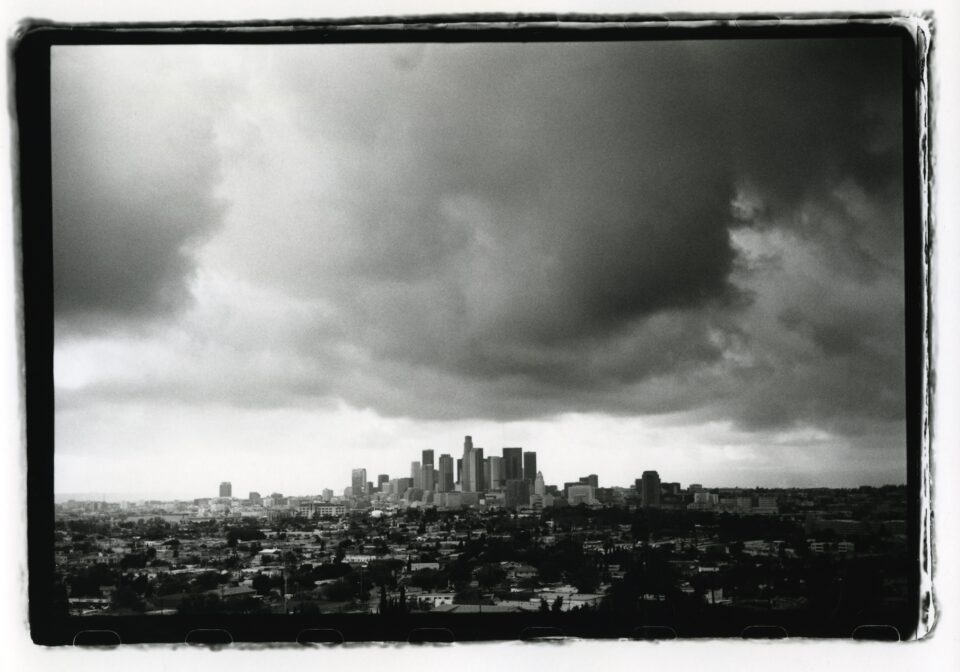

Photo by Estevan Oriol

I wanted to ask each of you: Is there a specific piece of art by one another that you’re especially drawn to?

RISK: The easiest one for me is Estevan’s LA hands. That’s so iconic of Los Angeles.

Estevan: For me it represents all of us. I always thought the best part of that picture wasn’t the picture, it’s what it meant for the whole city. I think we’re a really prideful city. The people that were either born and raised here, or the people that landed here and made this their home. Like RISK, he has the New Orleans background, but he’s LA. There are those types of people, then there are the other ones, they don’t count. They just come and suck from the city and they leave. They’re takers. But for us, that’s what that photo meant. Something for our city that we could represent anywhere in the world that we were. That’s one of the coolest things about that photo for me.

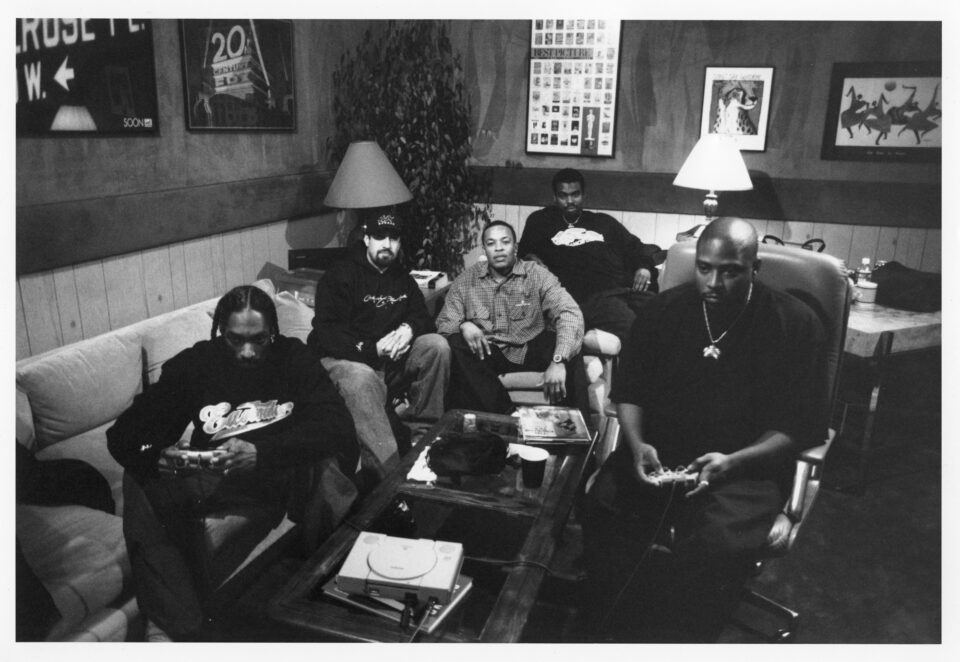

Snoop Dogg, B-real, Dre Dre, Nate Dogg, and Daz Dillinger

So many trends have come and gone throughout your careers—plus social movements, the birth of the internet, social media. What has been the key to staying inspired, relevant, and surviving through all of it?

Estevan: That I can make a living at it, support my family, and do something that I love to do on a daily basis is one thing that keeps me going. But then, being around other guys like this. When I come and see my friends that are kicking ass, it puts a big fire under me and makes me want to go home and work.

Jim: The three of us are actually lucky because we found an audience, and we can actually live out our creative adventure. All of us know people like us that are never going to be able to do what we’ve done. We all are able to make a good living at what we do. We’re lucky for that. I don’t think any of us want to give up, ’cause I don't think any of the three of us feel like we’ve achieved what we really want to achieve yet.

RISK: I’ve just recently felt like I’m at the starting line. I’ve spent my whole life getting to the starting line! When you’ve grown up with people that we’ve grown up with in Los Angeles, not to get too snobby, but you kind of get like, “Fuck the rest, we’re the best.” I just don’t look at shit. I look at my friend's shit.

Estevan: And we’ve had a lot of friends die because of where we live and how we live. I feel like we’re doing it for them, ’cause they couldn’t do it. Like Pauly B and Triggs [tattoo artist Mr. Trigger], Bronson. We’re still here. We survived all this shit that they didn’t, and I feel like we gotta keep carrying the torch. I’ve done everything that my friends did that died. I’ve done everything that my friends did that are in prison. That's why I do this for them. FL