Alvvays will also be taking over FLOOD FM for our “Hacked” series airing from October 9 through 13 at 10 a.m., 1 p.m., 5p.m., and 10 p.m. PST for a guest DJ takeover featuring hand-picked tunes and commentary. Mark your calendar and tune in here.

Once you’ve listened to an album hundreds of times, read everything there is to read about it, and seen it performed live on multiple occasions, how do you get even closer to that album? In the case of Alvvays’ latest record, you might try slurping the saccharine bev that gave Rev its name. Or, if logistics permit, you could ponder the lighthouses and crimson-sand shores of the band’s native Prince Edward Island. But there’s one option available without leaving the beanbag chair: pay five bucks on the App Store and download Stardew Valley, the genial simulation game in which you inherit your grandpa’s farm and set to work whacking weeds, planting crops, and schmoozing townsfolk.

“We get nerdy about little hermits, like Eric [Barone] from Stardew Valley, who did our ‘Many Mirrors’ video,” guitarist Alec O’Hanley says, reflecting on Blue Rev for its one-year anniversary and concurrent vinyl reissue. “We’ll hang out with him when we’re in Seattle. For us, that’s a nerdy moment of bliss, and fun.”

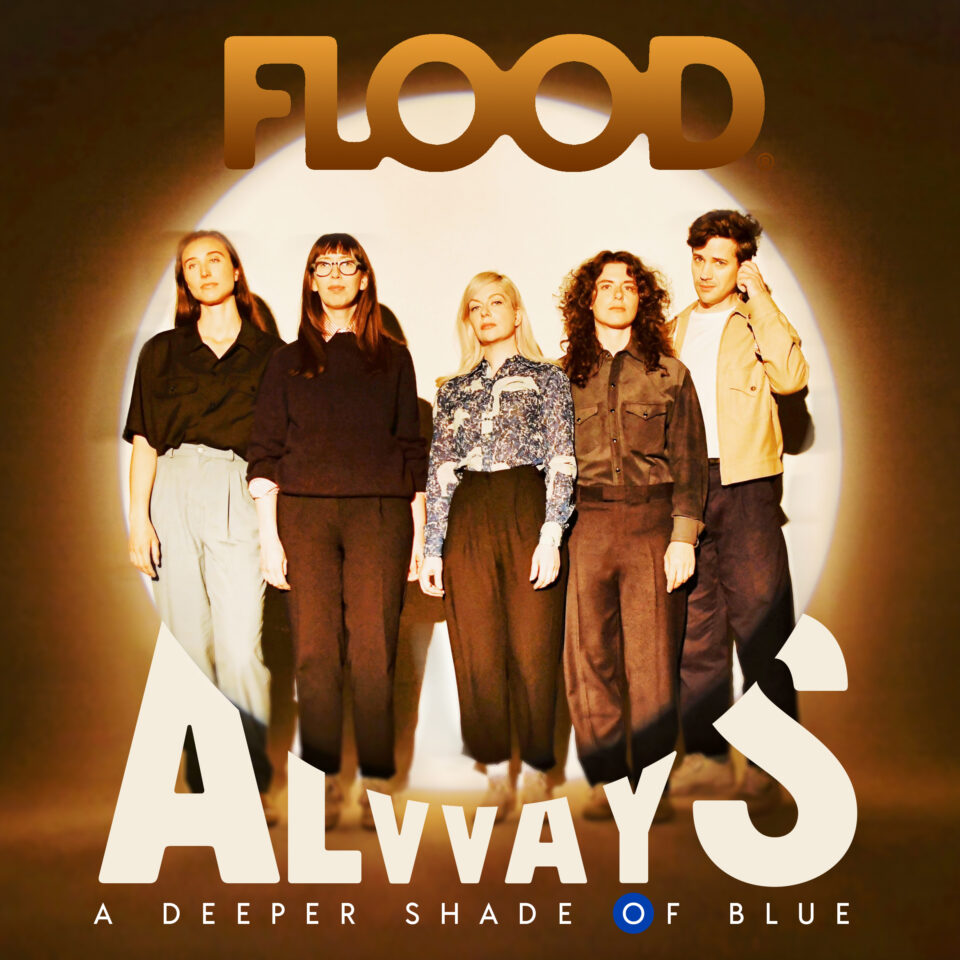

Photography by Shervin Lainez. Cover design by Jerome Curchod. Styling by Kallie Biersach at Intellectual Property. Makeup by Megan Kelly at Intellectual Property using Makeup Forever

The band’s third album, Blue Rev, has made such an impact in its short lifespan it’s as though it operates on Stardew Valley time, where days flash by in a matter of minutes, and it’s harvest time before you know it. Mere months after Blue Rev’s release, many publications—including ours—crowned it as the very best album of 2022. It enchanted the likes of Belinda Carlisle, Keanu Reeves, and Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy, whose acoustic dissection of “Pharmacist” O’Hanley called the “cherry on top” of their album cycle (“It was beautiful, devastating”). It engendered sold-out shows in North America, Europe, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. There was a breathtaking performance on The Tonight Show; a gift exchange with Narduwar; and the band got the creator of their favorite video game to make them a music video.

“They were playing this video game the entire time,” GRAMMY-winning producer Shawn Everett recalls of the studio sessions for Blue Rev. “I never played that video game. I tried it a couple times, but even that felt inspiring to me: Human beings who are genuinely into something, I find inspiring—no matter what someone is into. All that was kinda leaking into the atmosphere. When they get into something, they get into it.”

He is guilty of that, too, of course. A producer who seeks to renovate his approach with each project, Everett made sure that Blue Rev’s production incorporated deep dives that would intimidate even Jacques Cousteau, or that fish with the lightbulb on its head. “It’s not always for the faint of heart,” he continues. “Sometimes people don’t want to explore something that they’re already comfortable with. Even though you can always go back, it does psychologically feel like you’re breaking [the song] a little bit [when you take the tinkering too far]. I’m always looking for people who wanna go down that path with me, and I definitely found it in [Alvvays].”

“It’s honest, but it’s not self-serious. That combination just reads as intimacy. It’s hard to do, and they nailed it.” — Maggie Rogers on Alvvays’ music

“You don’t know until you go down the garden path whether there’s a beautiful meadow at the end, or a dump,” O’Hanley agrees. And while each song on Blue Rev ended up a verdant meadow, a couple of dumps had to be passed en route, such as a bridge section to their Smiths homage “Pressed,” which was ostensibly left among the soiled couch cushions and rusting tricycles. “We spent, like, two days trying to graft that in there,” O’Hanley says. “It kind of sounded like Laurie Anderson or something. Usually when we get into the weeds it’s because we haven’t listened to Molly [Rankin]. She’s got a good sense for what’s a viable route and what’s just meandering.”

Elsewhere, innovative techniques included taping iPod earbuds to hi-hat cymbals and to vocalist Rankin’s throat, various layering experiments, and recording straight through all 14 songs with only 10-second pauses between each. “They had to keep playing as if they were playing a live show; it just gets you out of your head a little bit,” Everett explains. Also in his toy chest was his artificial skull microphone, which mimics the human head for binaural recording. “His grasp on the science of sound is really interesting; he has one foot in the future and one foot in analog tape, and that’s really exciting to me, how those worlds collide,” Rankin muses. “Shawn remarked to us that he hadn’t met people who were quite so willing to do the deep dives—either tonally or arrangement-wise or emotionally, I guess—in some time,” O’Hanley adds. “I think we’ve found another kindred Canadian buddy in Shawn.”

“We try to subject our songs to the same scrutiny as the bands we hold dear, like The Smiths or even ABBA. We’ll truly look in the mirror, holding up those giant records, and try to get there. And we never do, but because we have at least unflinchingly attempted to, we get somewhere reasonably cool.” — Alec O’Hanley

“I remember thinking that it was kind of frontloaded with the really noisy songs,” Everett reflects. “And I thought maybe it wasn’t giving a full representation of how much character happens later on in the album. Where I changed my mind later: I think that having that noisy stuff at the beginning gives the album an identity, so when it wanders off of that path, I think your brain still has the feeling of living inside this loud, noisy sonic environment.”

The band-producer synergy is evident, even in the terminology they share (“garden path,” “science of sound”). The only topic on which they diverged, at least initially, was the album’s track listing. “In the beginning, he thought our sequence was bonkers and now he’s like, ‘It’s perfect—I can’t believe we did that at 6:30 in the morning,’” Rankin laughs. “But I was actually crying at the time because I was so devastated that we were having to do it in that state of mind after spending so long writing and making the album.” To finalize the sequence before the vinyl deadline, the band and Everett had to pull a last-minute all-nighter. (“We’re slaves to the wax,” O’Hanley drolls.)

Opening with the fighter-jet Fender Jaguar tones of “Pharmacist,” Blue Rev begins to wind down with quite the opposite: “Pretty quiet out here, it’s abundantly clear / That no one’s been coming for me / No encouraging sounds, helicopters or hounds,” Rankin whispers on penultimate track “Lottery Noises,” an electric piano cooing beneath her. The one-two-three punch of “Pharmacist,” “Easy on Your Own?,” and ebullient fan-favorite “After the Earthquake”—the opening that Everett refers to above—gradually gives way to these more reserved offerings, beginning with the gossamer night breeze of “Tom Verlaine” at number four and continuing from there to smile and sigh in roughly equal measure.

“It’s neat for us to be in front of people who are into different music. It’s also cool to just get out there and fall on your face with the crowd. You’re starting from zero and it’s a good team exercise.” — Molly Rankin

Now, after you’ve seared Blue Rev into your frontal cortex, it’s impossible to imagine it structured any differently—for the bared-teeth punk spin-off “Pomeranian Spinster” (one of Everett’s favorites) to sink into anything other than the stirring, Carlisle-inspired fable of new beginnings; for the mordacious machine-pop of “Very Online Guy” to release into anything other than “Velveteen” in all of its silky, sorrowful glory. Maggie Rogers, whom Alvvays supported on her recent North American tour, testifies to the importance of that lead track coming first: “I have such a vivid memory of the first time I heard ‘Pharmacist’ in the car,” she recalls. “I was driving down the highway in Los Angeles and immediately felt so nostalgic, but still so present, [then] I checked out the rest of the record and just fell in love. It became a real soundtrack to my spring, and I was so stoked when they were down to come on tour.”

Despite how concrete Blue Rev is now, Everett points out that “When you’re working on something, everything is in flux. In the back of my head, I’m always hearing an infinite amount of options—like, I’m thinking you could change anything. Before it’s out, it’s still a realm of infinite possibilities. It’s hard to hear it as a solidified block.” (The same goes for our Stardew Valley farms; maybe I should’ve planted apricot saplings rather than cherries.) In Everett’s case, what helped slot things into place was his wife, Belgica Vargas, who gets points for her assist. “My wife isn’t always into everything I work on, but she was really into this album,” he shares. “As she was playing it all of the time, I was hearing it through her ears in a different way, and the sequence clicked for me. When you’re with someone for that long, your tastes inform each other’s,” he says by way of summary.

That conceit is what makes Alvvays’ heart beat—the source of its magic. “Alec and I have generally learned to trust each other’s taste,” Rankin shares. “Our little filtration system is all we know and nothing about that will ever change, and if that’s something that we don’t feel comfortable doing anymore, or we don’t want to go through that process anymore, we would probably cease to be making albums.” Responding to her point, O’Hanley offers, “It can be a harrowing process at times, but that’s always been the case—the Venn diagram intersection of our tastes and not deluding ourselves about what we’re documenting and whether it serves the song. We try to subject our songs to the same scrutiny as the bands we hold dear, like The Smiths or even ABBA. We’ll truly look in the mirror, holding up those giant records, and try to get there. And we never do, but because we have at least unflinchingly attempted to, we get somewhere reasonably cool.”

It should be surprising that Alvvays’ humility has endured despite the hailstorm of adulation heaped on their “reasonably cool” music over the past year. But it isn’t. Sure, they have a more substantial touring crew now—“We’re on a tour bus; Alec and I aren’t trying to parallel park a van and trailer in Manhattan,” Rankin laughs—but otherwise, the fundamentals, their filtration system, remains comfortingly, endearingly unchanged.

The same goes for the live show context. Rankin says of the Maggie Rogers tour, “It’s neat for us to be in front of different people who are into different music, and sort of explore that world a little. It’s also cool to just get out there and fall on your face with the crowd. You’re starting from zero and it’s a good team exercise: just play the songs as best you can and come out of it feeling good about what you did. It’s a different muscle, walking on stage to people who have no idea who you are, and [knowing] how to interact with them, and even what to put in the setlist.”

“Even on Late Night, I was coloring the drum skin with a Sharpie at, like, three in the morning before we flew out. We’re still on our hands and knees, piecing things together, and pulling pedals out of Mono bags on the airport floor.” — Molly Rankin

Rogers, who was smitten with the band after seeing them play the Bowery Ballroom while she was studying at NYU, astutely summarizes Alvvays’ blanket appeal: “It’s honest, but it’s not self-serious,” she shares. “That combination just reads as intimacy. It’s hard to do, and they nailed it.” Those core tenets—honesty, not taking themselves too seriously—also explain why the band is willing (and able) to adapt to these contrasting live contexts: an opening act hoping to entertain some newcomers; a formidable headliner zipping through the entirety of Blue Rev (plus a few old favorites) without breaking a sweat. They’ve even reached the level of mainstream bizarreness that is American late-night television, for which they employed an orchestral string section.

“Even on Late Night, I was coloring the drum skin with a Sharpie at, like, three in the morning before we flew out,” Rankin says, belying the magnificence of the “Belinda Says” performance. “We’re still on our hands and knees, piecing things together, and pulling pedals out of Mono bags on the airport floor.” Replace pedals with seeds and Mono bags with burlap sacks and you’ve got the premise of Stardew Valley. It’s these physical, everyday mundanities—and the humble gratitude that underpins them—that add up to something special. As Rankin puts it, “Anything that we’ve tried to manifest has been a debacle, and we’ve learned that just taking it one day at a time was the right approach for us; because any new, exciting thing has come out of the sky for me.”

Just like in video games; just as in real life. FL