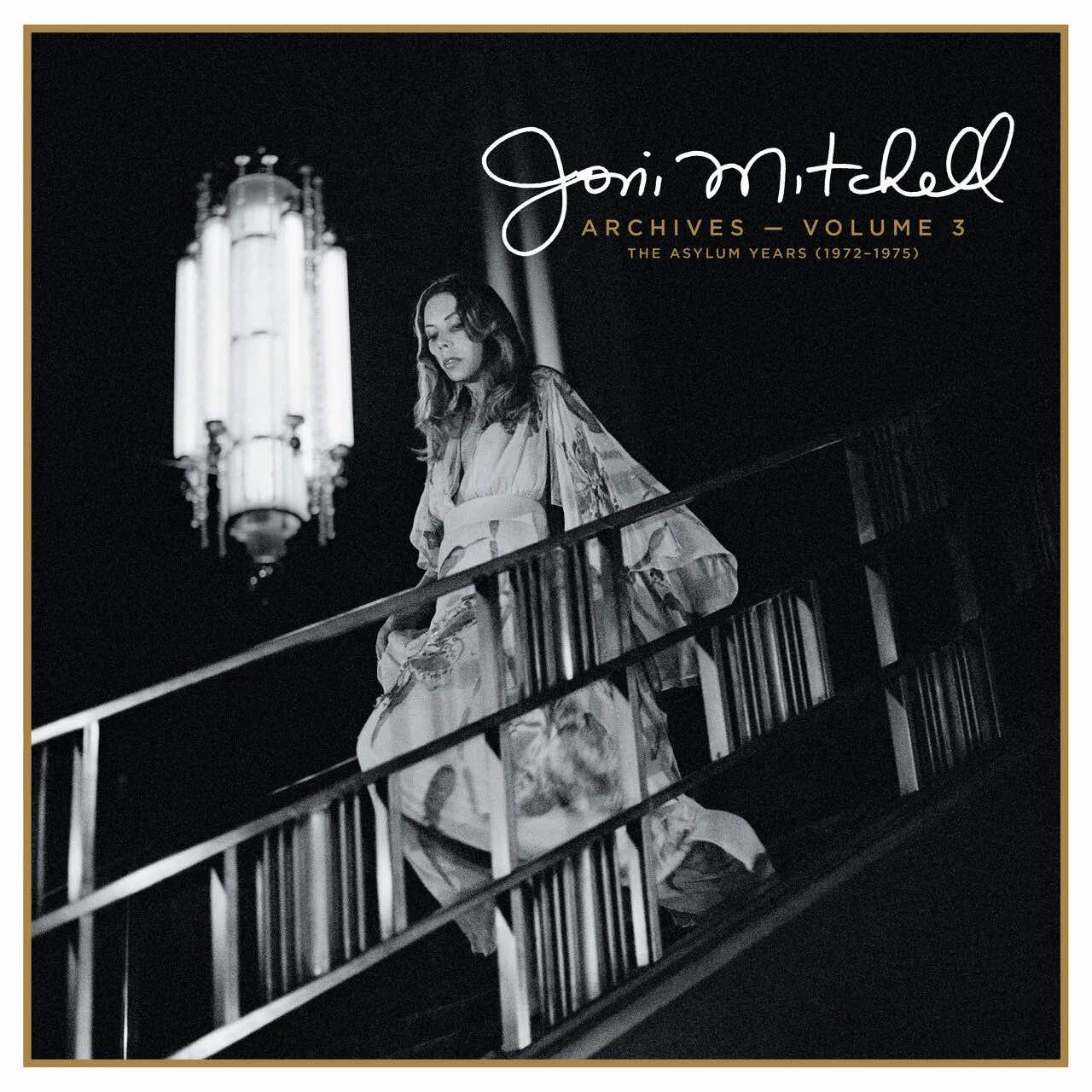

Joni Mitchell

Archives, Vol. 3: The Asylum Years (1972-1975)

RHINO

By 1972, Joni Mitchell was disillusioned: with having become a folkie icon and all the earnest lyrical and sonic symmetry that went with it; with the further possibilities of stoking the star-making machinery behind the popular song of Los Angeles; with her relationship with James Taylor and his rising star; with singing and dreaming in solitary fashion. So she packed her bags, left LA, split the folk scene (mostly), welcomed musical collaboration, and began an increasingly wilder sojourn into jazz’s experiments in textural arrangements and rhythm, turning her highly personal lyrical output inward to study who she was (and could become) as an artist, avatar, and observer.

What the third volume of Mitchell’s Archives series does in its fantastic breakdown of her Asylum Records years—covering 1972’s For the Roses, 1974’s Court and Spark, and 1975’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns—is present an artist’s sketchbook in full: the blossoming of fresh goals for her lyrics, vivid rainbow arrangements and lively complex grooves to make those words cut deeper, and a more expansive vocal prowess to make it all hum. By the time we get to the dissection of her slithery classic Summer Lawns and its illustrative, illuminating two albums of A&M Studio sessions (the best of this box), we’re given real entrée into process—how she developed her elegant tales of frustration with crushing patriarchies and commonalities while toying with the ambience of her sonic palette and its set up for the skeletal, free sound and poetry of her true masterpiece, 1976’s Hejira.

A handful of live albums within Vol. 3 present an in-concert picture of a lone artist becoming a powerful, respected (and respecting) band leader. In particular there’s Mitchell guiding the ’70s version of cool Californian jazz, Tom Scott & the L.A. Express, through the breezy, complicated paces of “You Turn Me On, I’m a Radio” and “Free Man in Paris” at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in 1974, with the singer turning into a modern Anita O’Day in the process. Still, it’s the weird, rare studio stuff that binds this Mitchell box and makes it shine—from the never-before-released “Like Veils Said Lorraine” and its incomplete thoughts on divine reckoning, to the quirky rhythm section’s backing on the heartbroken “See You Sometime” ballad, to her working out a flighty “Raised on Robbery” with a chugging, charming Neil Young and the Santa Monica Flyers in eerie offbeat fashion.

Yet Mitchell’s own four-part solo “Piano Suite” and her early alternate take on “Trouble Child” are the highlights of her Court and Spark demos. Along with a simplistic but illuminating take on “Help Me,” Mitchell’s spare clicks and clucks show how each track will blossom and fly on the full album’s versions. Add in the test versions of a snaking “The Jungle Line,” a stoic “Edith and the Kingpin,” and the mini-epics of “Shades of Scarlett Conquering” and “Dreamland”—all downright ominous—and this third volume is worth digging into as the best of Rhino’s Archives collections. I’m already excited for Vol. 4.