This article appears in FLOOD 12: The Los Angeles Issue.

For nearly 60 years, the city of Los Angeles has been significantly defined by its music venues. Many LA clubs are internationally famous, known the world over for being the regular haunts of immortal musicians and the birthplaces of iconic groups, as well as for incubating these scenes that influenced other musicians across the continent and around the globe. Here, we take a trip through the decades to see how the landscape of live music in the city has evolved up to the present day.

1960s

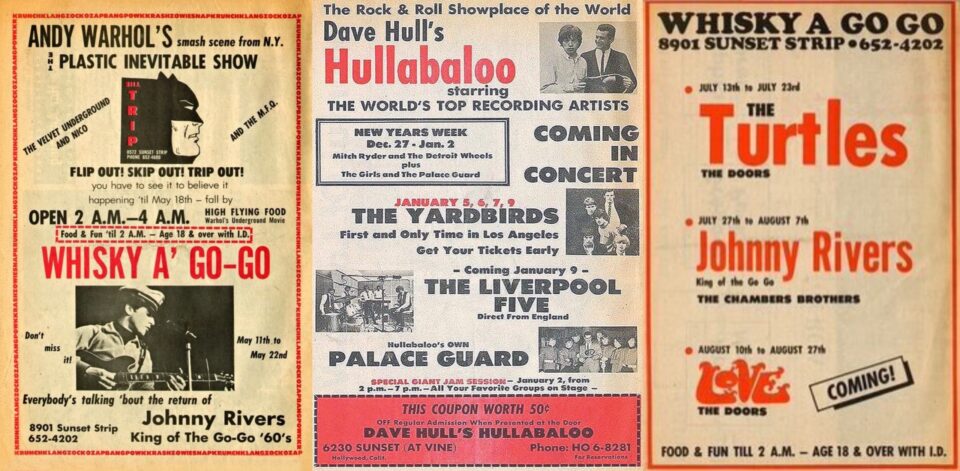

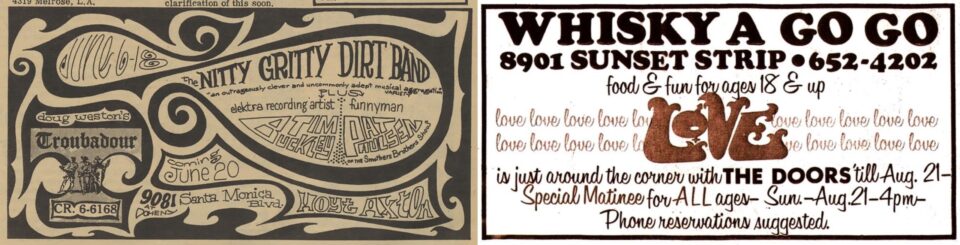

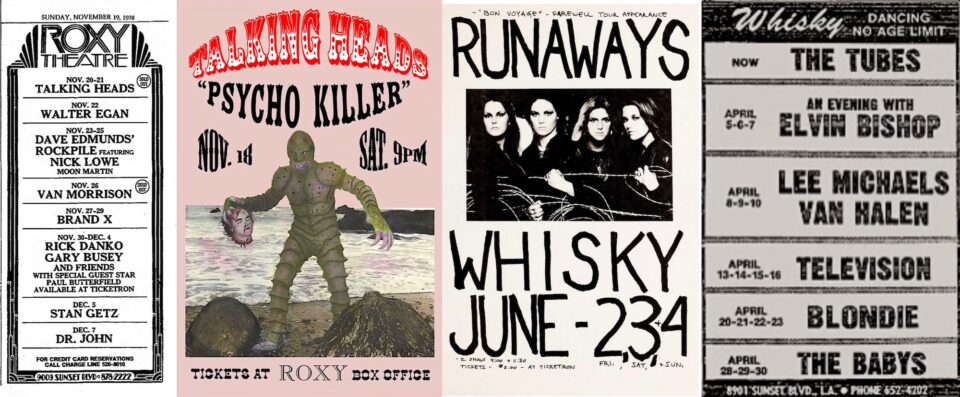

Rock ’n’ roll began in the 1950s, but it wasn’t until the mid-’60s that the Sunset Strip became its official LA home, thanks primarily to the 1964 opening of the Whisky a Go Go. Here, dancers-turned-DJs kept the groove going on the state-of-the-art sound system. The Doors had a particularly infamous stint as the house band at the Whisky, as depicted in Oliver Stone’s 1991 biopic, for which the club’s original red-painted exterior was faithfully recreated.

Johnny Echols of Love, another regular band at the Whisky in the mid-’60s, remembers this time well. “Groups wouldn't play there because they weren’t sure they were going to get paid,” he recalls. “The booker there was a personal friend [of ours] and she guaranteed that we would get paid. They booked us for a week and we got paid and we told other bands like The Doors and Iron Butterfly that it was OK to play there. It became the ‘in’ place, because many of the clubs back then would either give you a bogus check, or didn't pay, or paid you less than what you initially asked for. It was a big deal to actually play and count on getting paid.”

“Sunset Boulevard at that time on a Saturday night was two rows of cars that were almost dead stopped all the way down Sunset, from the Whisky to the other end where the Hullabaloo club was. It was all old Hollywood clubs that had been turned into youth clubs.” Jim Evans a.k.a. TAZ

Led by the brilliant Arthur Lee, Love would play four sets a night, emptying and refilling the Whisky over and over again. The Whisky was one of many venues on the Sunset Strip drawing hundreds of fans a night on a regular basis during the 1960s. Among the others were Hullabaloo, Ciro’s, Gazzarri’s, Pandora’s Box, The Sea Witch, The Galaxy, The Trip, and The London Fog, all of which regularly featured local bands like The Standells, The Seeds, The Byrds, and The Turtles.

“Sunset Boulevard at that time on a Saturday night was two rows of cars that were almost dead stopped all the way down Sunset, from the Whisky to the other end where the Hullabaloo club was,” remembers renowned music poster artist Jim Evans, a.k.a. TAZ. “You could start at one end of the street, you’d have a bunch of girls jump into your car, and you’d be off to a party in the hills before you even got to the Whisky a Go Go. It was like one big gigantic party, where everyone was just leaning out of their cars handing out joints to each other, with clubs all up and down the Sunset Strip. People were wrapped around the blocks. It was all old Hollywood clubs that had been turned into youth clubs.”

It was the Whisky, however, with its prime location, good-sized room, high-end sound system, and professional sound engineer which really attracted musicians and fans alike. “The shows there sounded very good,” says Echols, “and many musicians did live albums from the venue.”

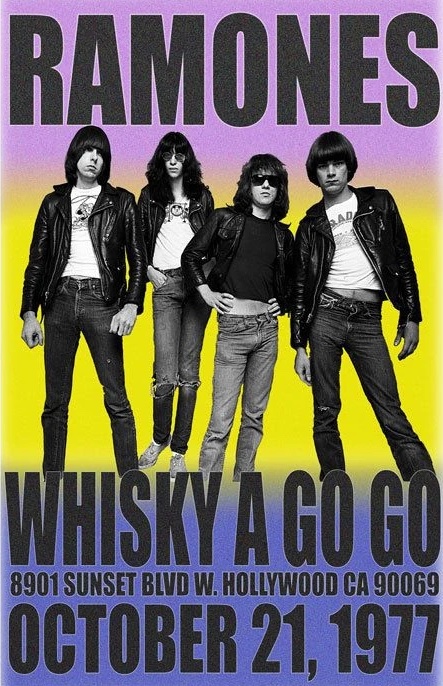

1970s

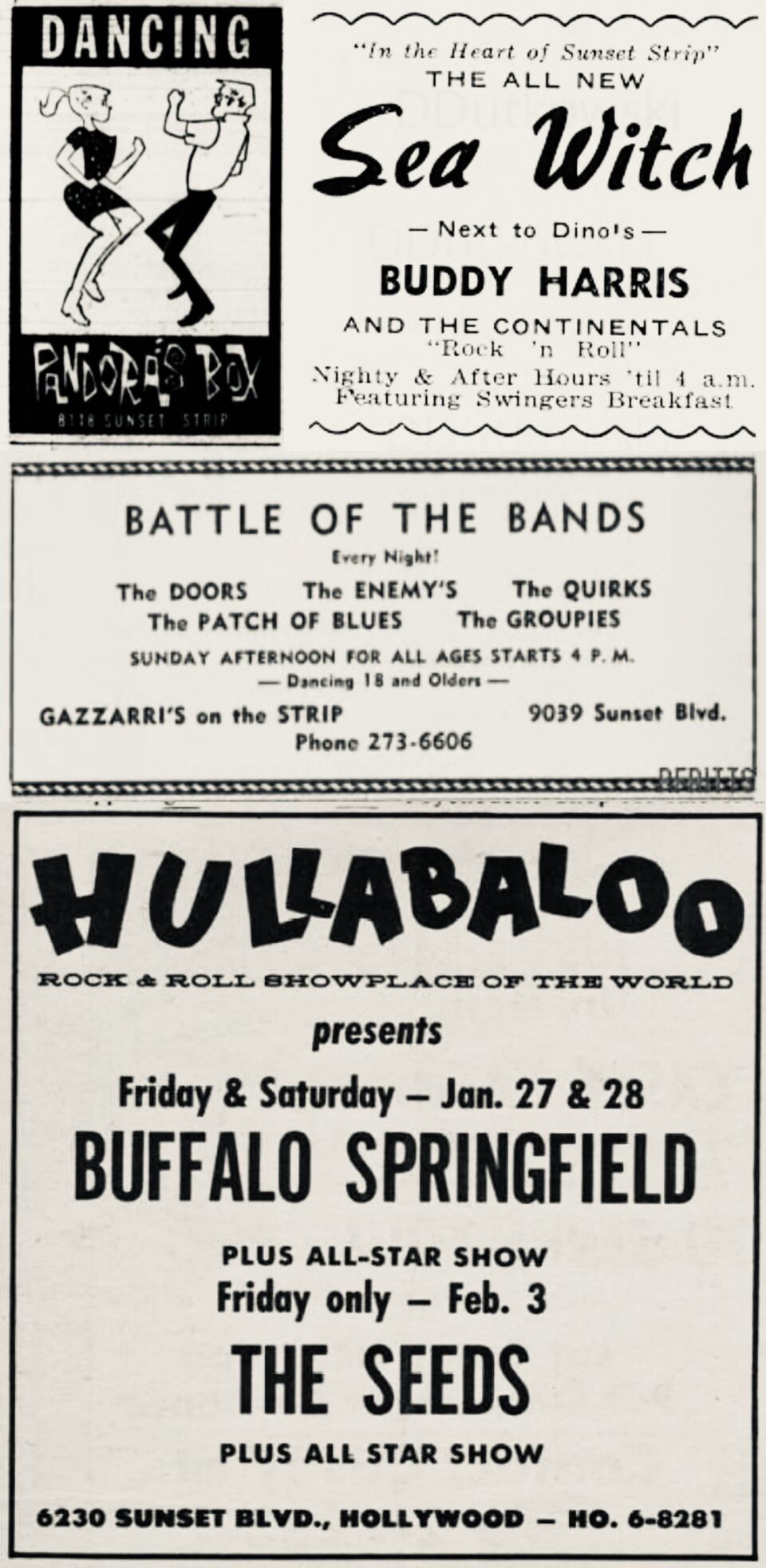

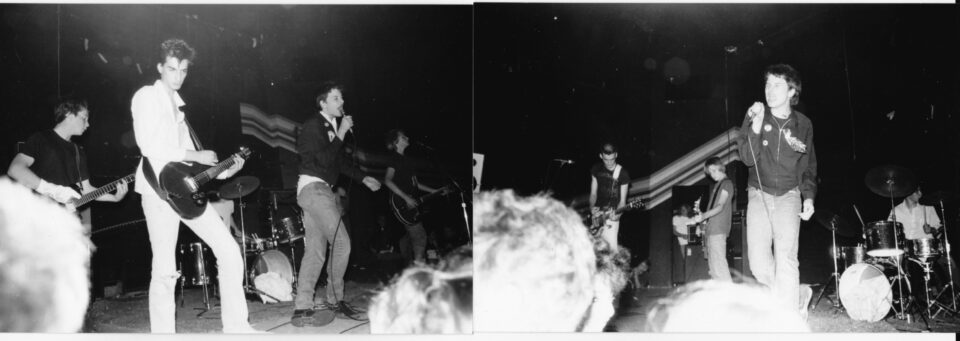

“The first club we ever saw a band play was the Whisky in 1978,” says Steve McDonald of Redd Kross. At the time, McDonald and his brother and bandmate Jeff were 11 and 15, respectively. The Whisky had no age limit, and with multiple shows each night, the early shows started at 8 p.m. On this particular night, the McDonalds convinced their parents to take them to the early show by the San Francisco punk rock band The Avengers.

“We were afraid the punk rock movement was going to be like what we'd heard about in the press: really violent and people with safety pins in their bodies, all the sensationalist stuff coming out of London,” says Steve McDonald. “We were scared because we weren't ‘authentic’ punk rockers and [thought] they were going to grab us, hold us down, and shave our heads on the spot—even though we had green food coloring in our hair. [But] the crowds were artistic types that thought it was a trip that these suburban tweens had found their way into their little scene.”

“We were afraid the punk rock movement was going to be like what we'd heard about in the press: really violent and people with safety pins in their bodies, all the sensationalist stuff coming out of London." —Steve McDonald, Redd Kross

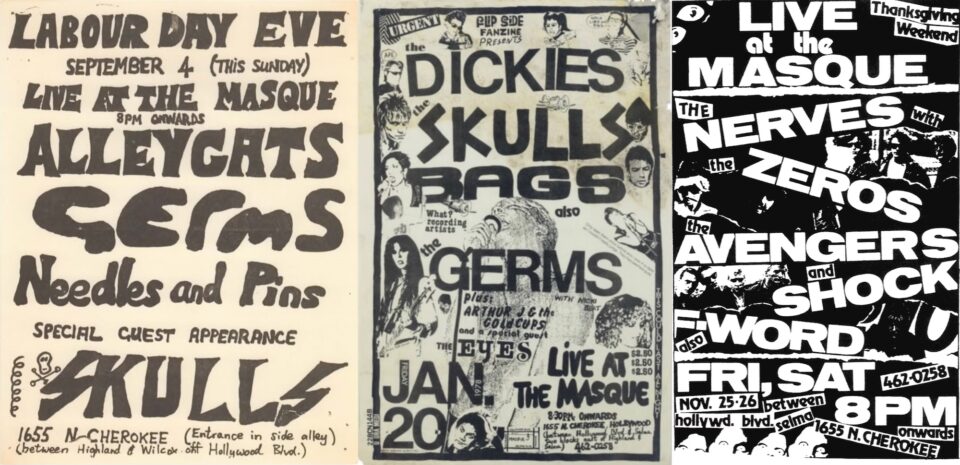

The McDonalds were also witness to the insular group that revolved around The Masque. Located in the basement of the Pussycat Theater on Hollywood Boulevard, The Masque was what the brothers characterize as “ground zero for the birth of the LA punk scene”—even though they couldn’t talk their parents into taking them to that particular venue.

“The Masque is old school,” says Bryan Ray Turcotte, a San Francisco–bred, Los Angeles–based authority on punk rock and member of the band Black Market Flowers. “It was run by Brendan Mullen, who paid the landlord $200 in rent. They were just having fun shows and it was legendary, but there was no bar and no staff. They had the Screamers and the Germs, but it barely lasted a couple of years. All the graffiti they did in there, I think, is still there.”

Mullen moved the club to other Hollywood locations under such names as The New Masque, Masque Two, and The Other Masque, booking now-legendary bands like The Cramps and Dead Kennedys before finally throwing in the towel in 1979.

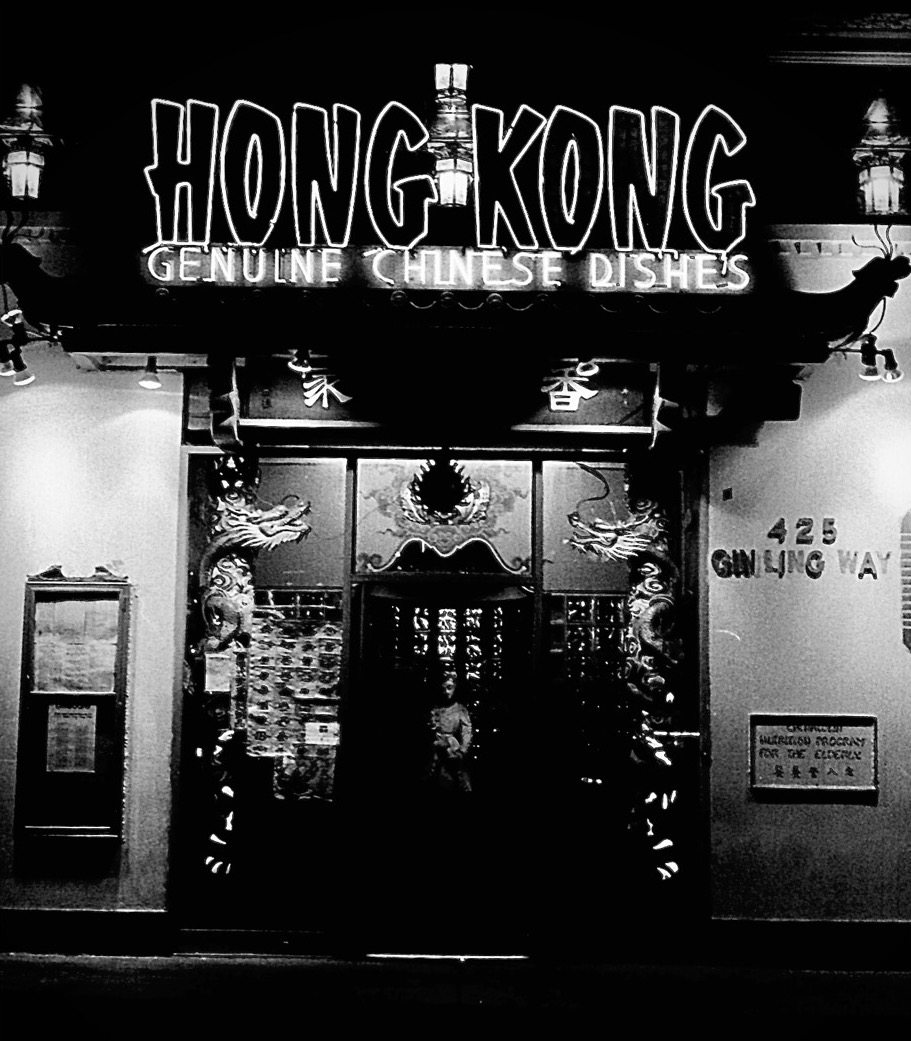

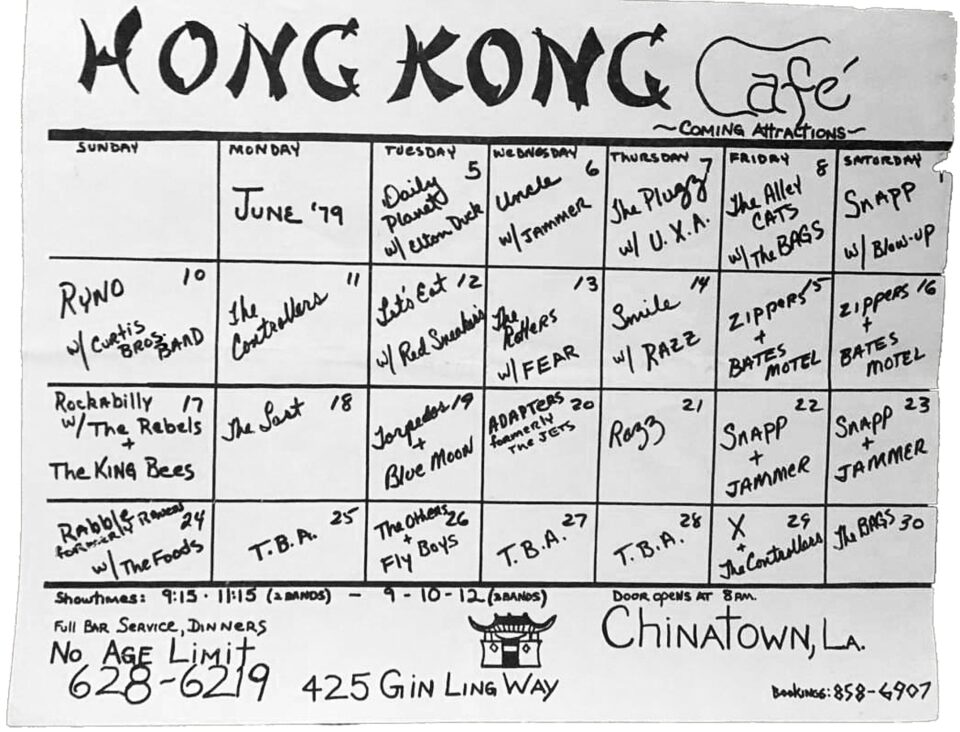

Located in LA’s Chinatown, Hong Kong Café was another haven for Redd Kross, who shared the venue’s stage with many of their favorite bands. “Chinatown was this safe, weird little enclave that hosted the LA punk scene for a year and a half to two years,” Steve McDonald recalls. “Whoever was still around from The Masque were now focused out of Chinatown.”

Madame Wong’s was the new wave counterpart to the Hong Kong Café, and the two clubs were located diagonally across from each other in the Chinatown Central Plaza. Wong’s tended to book artists with greater crossover potential, such as Oingo Boingo, The Police, Ramones, The Motels, and The Plimsouls. Madame Wong’s later opened a location in Santa Monica, dubbed Madame Wong’s West.

Hong Kong Cafe / photo by Edward Colver

“Chinatown was this safe, weird little enclave that hosted the LA punk scene for a year and a half to two years." —Steve McDonald, Redd Kross

Madame Wong’s Restaurant / photo by Greg Allen

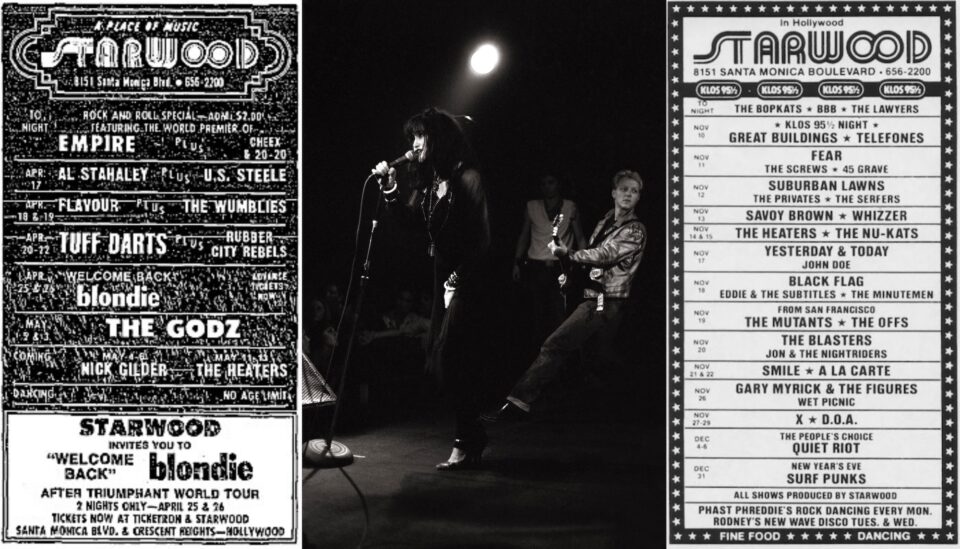

Occupying a prime Santa Monica Boulevard spot just a few blocks south of the Sunset Strip, the Starwood was another major venue for punk shows in Los Angeles in the 1970s, though it also booked hard rock and heavy metal bands—Van Halen first attracted the attention of the local music industry while playing there. Music-lover-turned-music-photographer Greg Allen remembers the venue as his favorite. “It had different rooms,” he says, “so if you weren’t digging the opening band, you could sit in the other room, play pinball, or just chill out on the couch. I loved all the venues up and down the Strip, but also the Palladium and Santa Monica Civic; later Club Lingerie became my haunt."

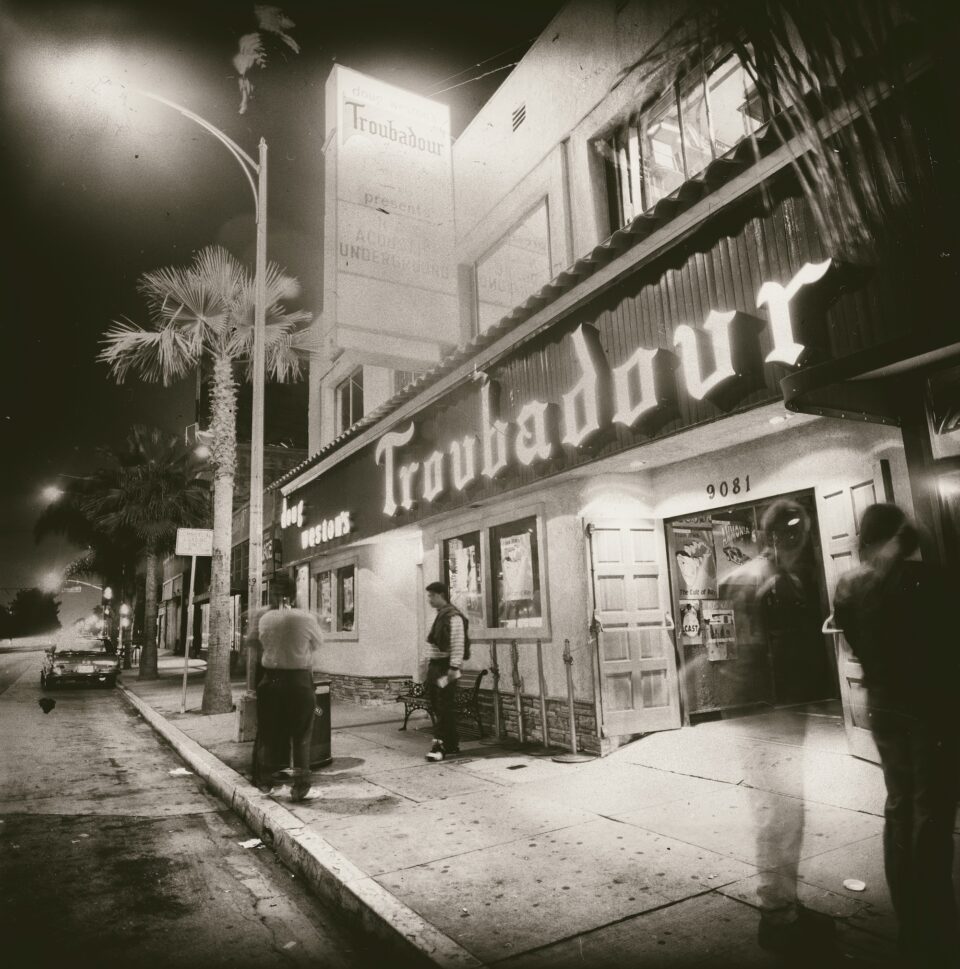

Allen also recalls when, down the street from the Starwood, the storied Troubadour still had seats. It was during the switch from the hippie era to the punk era that many venues removed their seating to better accommodate the rowdy behavior of their audiences. Says Allen, “I remember going to The Roxy in ’79 or ’80 to see Rachel Sweet. We came in at the tail-end of the first band. As soon as that band left the stage, instead of crowding up front like you would nowadays, everyone sat on the floor to wait for the next band.”

X at Starwood / photo by Greg Allen

The Adolescents, Starwood, 1980

1980s

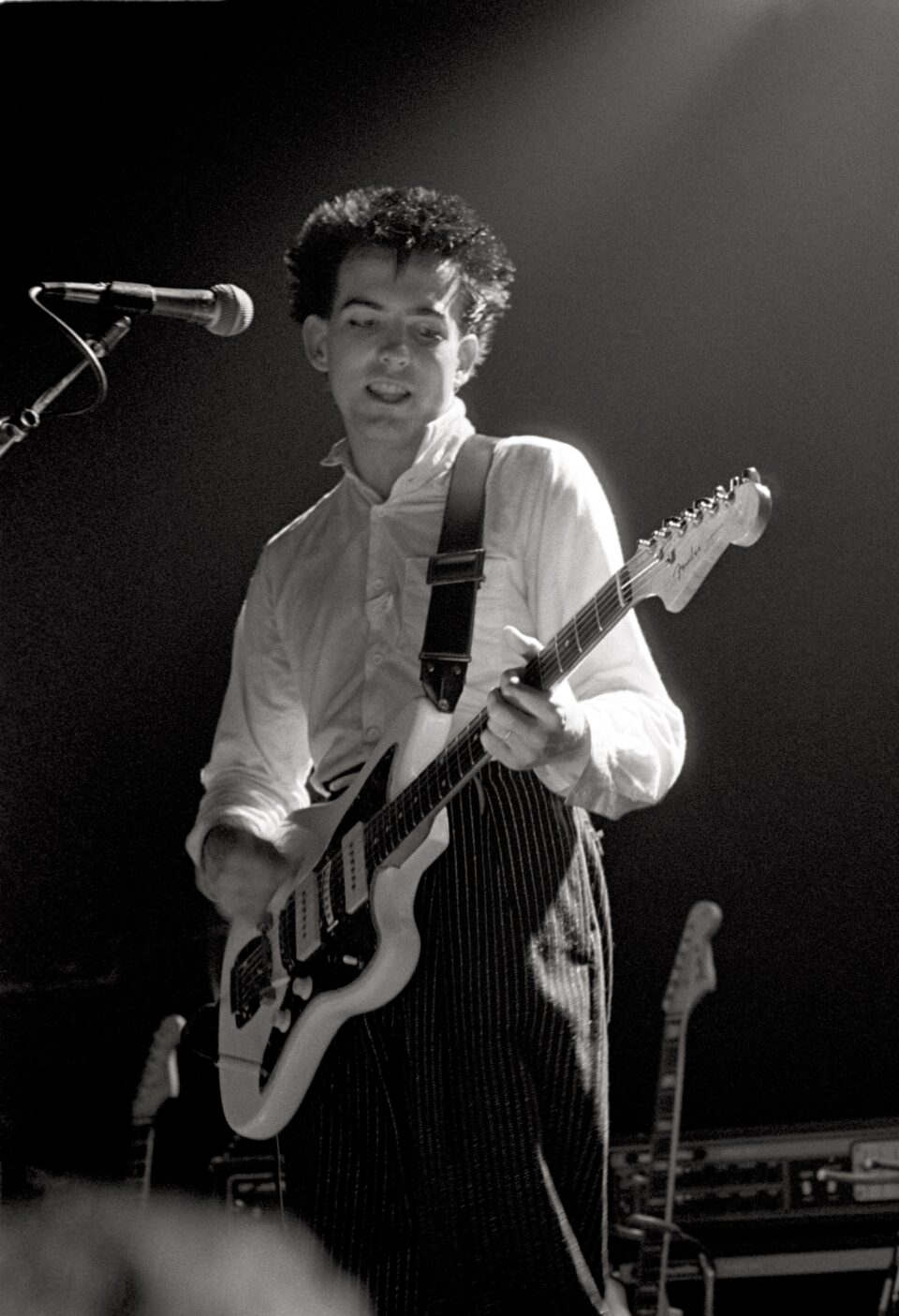

When The Cure played the Whisky in 1981, Allen was there. He also found himself far afield in Reseda at Chuck Landis’ Country Club: “That was a great stage because of the way it curved around; even if you got there late, you could still get really close up front.”

Allen also saw Rockpile, Gang of Four, and Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark at the Country Club, as well as James Brown’s legendary show there in 1982. “There’s a picture on the internet of James reaching and everyone’s trying to shake his hand, and I'm buried right in there.”

During the 1980s, “pay to play” (where artists essentially had to pay the venues for the opportunity to perform) became a pervasive characteristic of the Sunset Strip clubs—and by extension, the Troubadour—as well as a source of discontent for bands who needed places to perform.

The Cure, Whisky a Go-Go, 1981 / photo by Greg Allen

Belinda Carlisle of The Go-Go’s, Whisky a Go-Go, 1981 / photo by Greg Allen

“Actually, the Troubadour didn’t do ‘pay to play,’ but you would only get paid on discount tickets,” Jeff McDonald clarifies. “They would give you these blank discount tickets and you would stamp ‘Redd Kross’ on them. You were supposed to go to the local record shops and other places and leave a stack of your Redd Kross Troubadour stamped tickets. The idea was that whoever passed through the door and got $3 off using your stamped ticket, you would get paid on that ticket.”

By the mid-’80s, Redd Kross were selling out the Troubadour without strategically distributed discount tickets. Before one Redd Kross show, however, the band threw a stack of discount tickets out the window of their dressing room onto a queue of fans waiting to get into the venue. “They didn’t pay us a single penny that night because we had pulled that stunt,” says Steve McDonald. “They used to run it like the mob. They were really militaristic. The hair metal bands were so willing to play that kind of game. That mentality worked for them. They thought it was professional. We were rolling our eyes and not buying into it.”

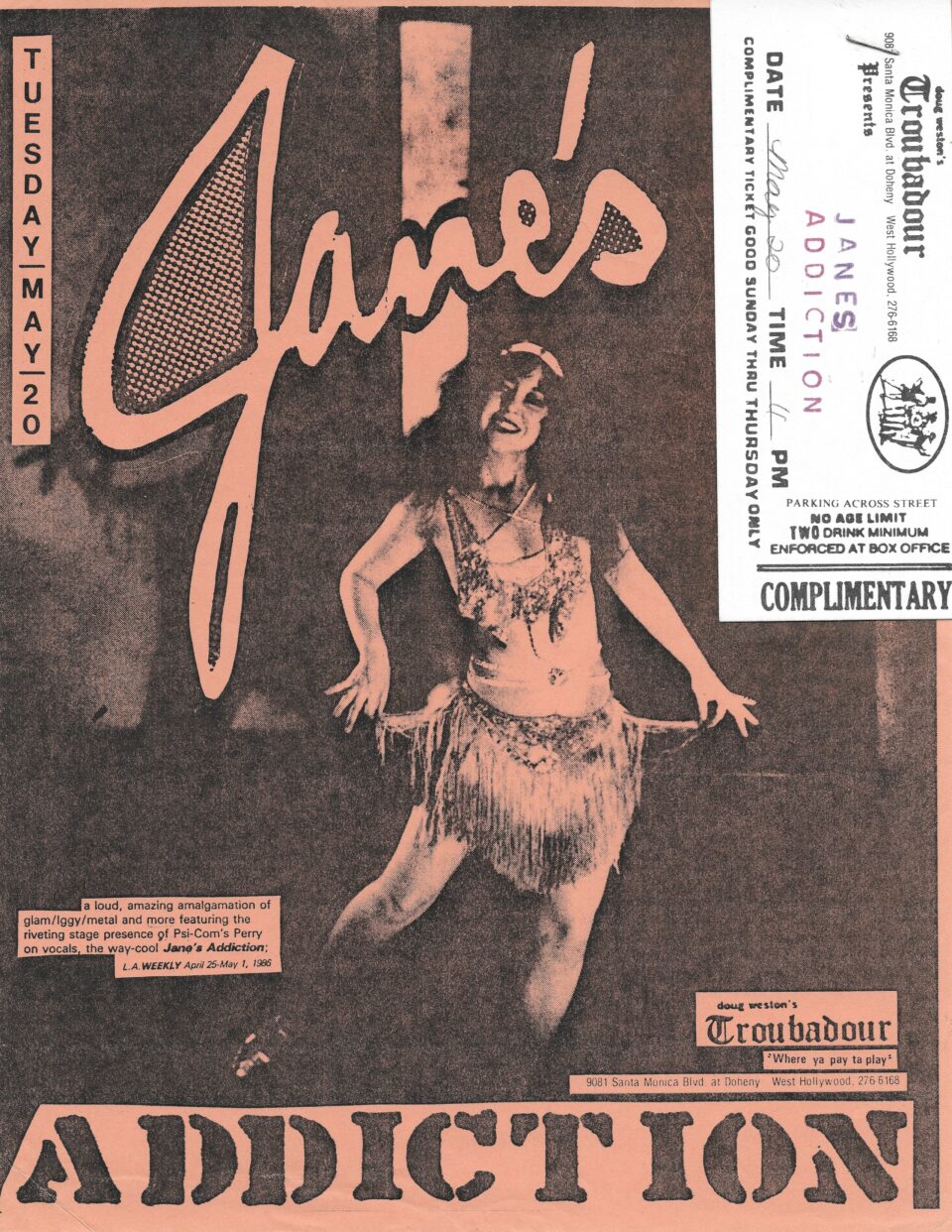

Doug Weson’s Troubadour / photo by Greg Allen

“Coming from the Northern California punk scene, we were appalled by the Sunset Strip,” says Turcotte. “It was a shock. These guys are coming off of KISS and the Scorpions and we were way past that. We just didn't understand that scene. It felt old. I didn't relate to Ted Nugent and Van Halen. We were throwing away the corporate rockstar idea. We thought it was going to be like our NorCal DIY scene, only bigger. It was actually more condensed and smaller.”

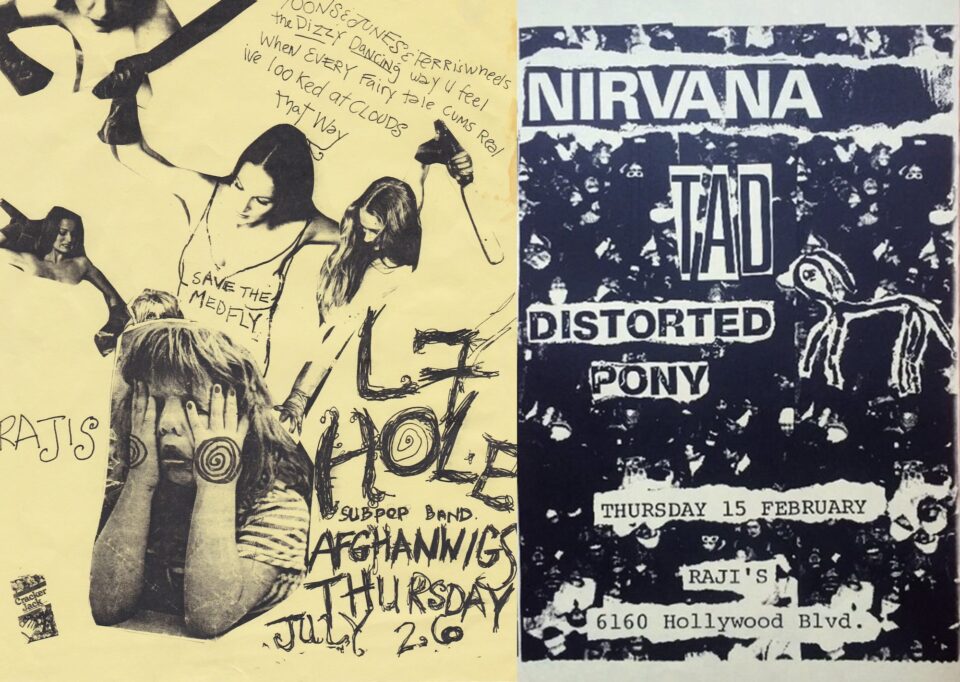

It worked out for Turcotte, however; while everyone was clamoring to get into hair metal shows, he was able to see bands like The Smashing Pumpkins and Nirvana with 50 people in attendance. The close-knit post-punk/alternative rock scene in Los Angeles had an intimacy to it and an honesty without any corporate element attached.

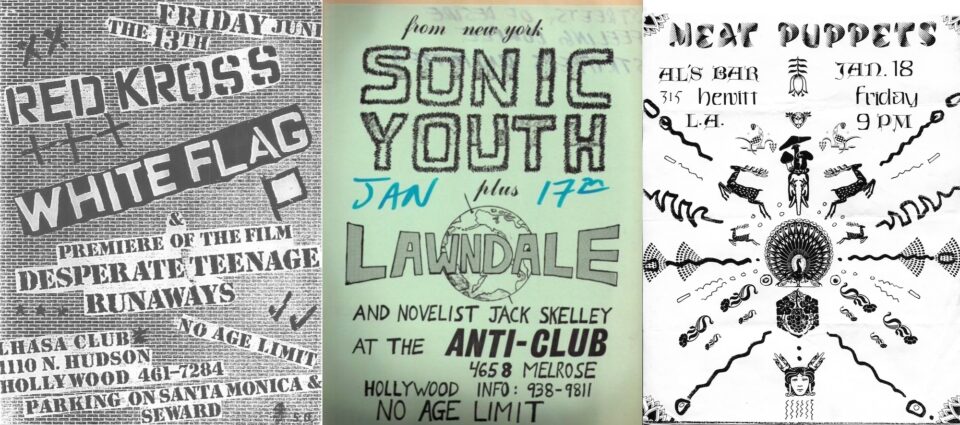

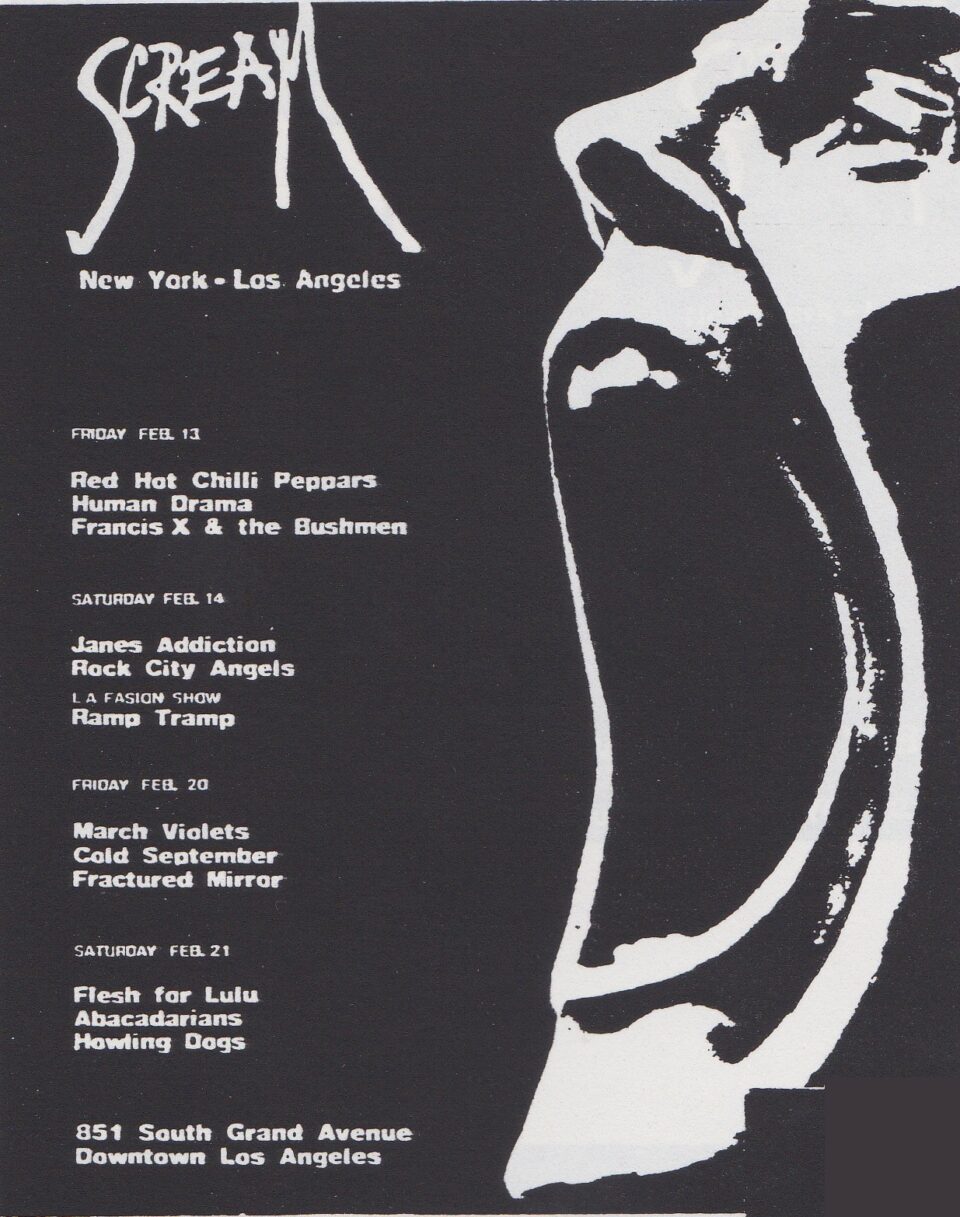

This communal scene revolved around the Anti-Club at the far east end of Melrose Avenue, Lhasa Club on Santa Monica Boulevard, Raji’s in Hollywood, Al’s Bar in Downtown LA, and Brendan Mullen’s Club Lingerie. “We found the downtown post-punk bands like Jane’s Addiction and Kommunity FK at places like Scream, Al’s Bar, English Acid, Raji’s,” says Turcotte. “The big venues were booking metal and rock. We would go to see Jane’s Addiction downtown and there would be 100 kids there.”

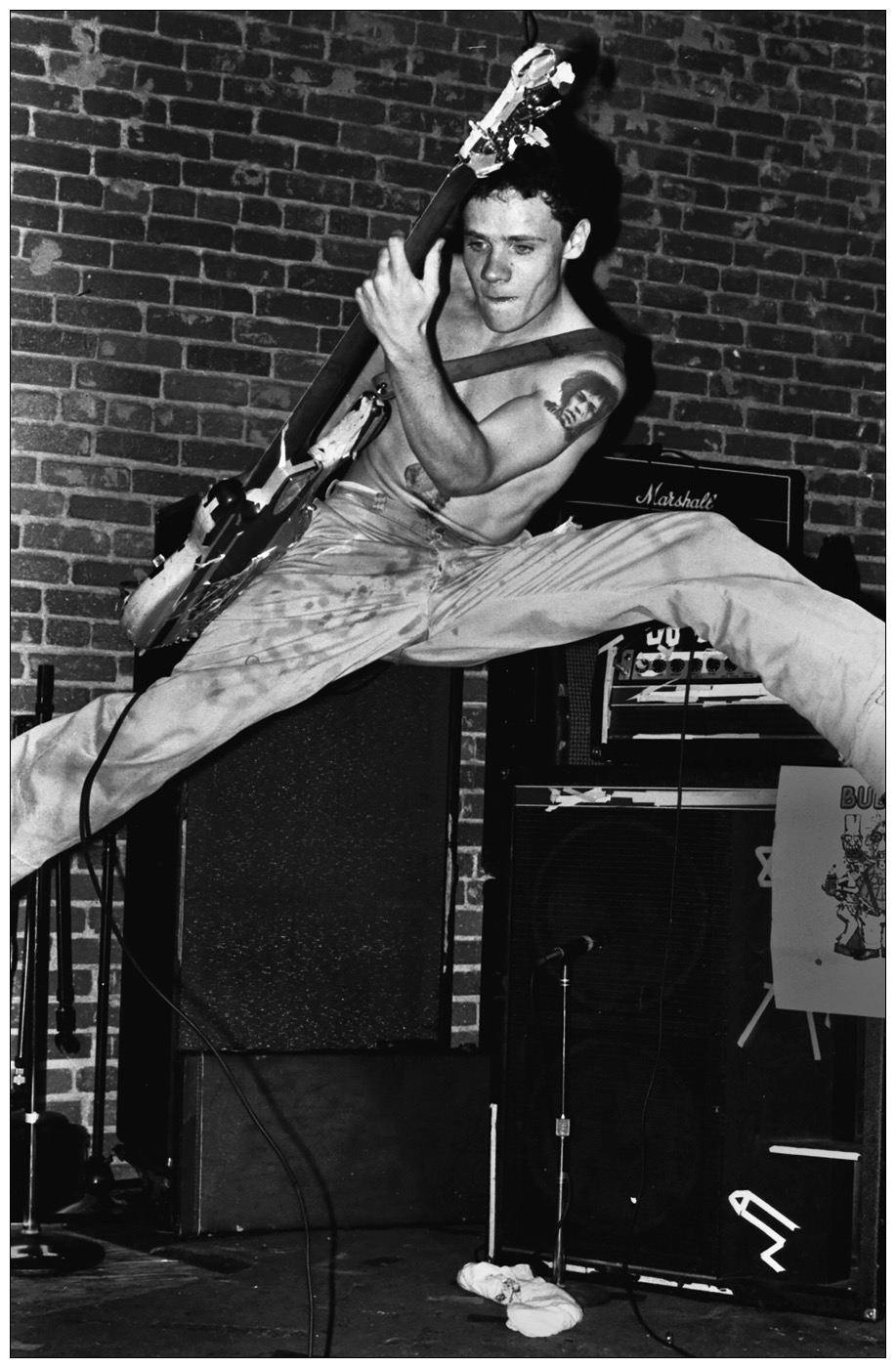

Flea of Red Hot Chili Peppers, Club Lingerie, circa-1983 / photo by Edward Colver

“Coming from the Northern California punk scene, we were appalled by the Sunset Strip. It was a shock. These guys are coming off of KISS and the Scorpions and we were way past that. It felt old." —Bryan Turcotte, punk historian

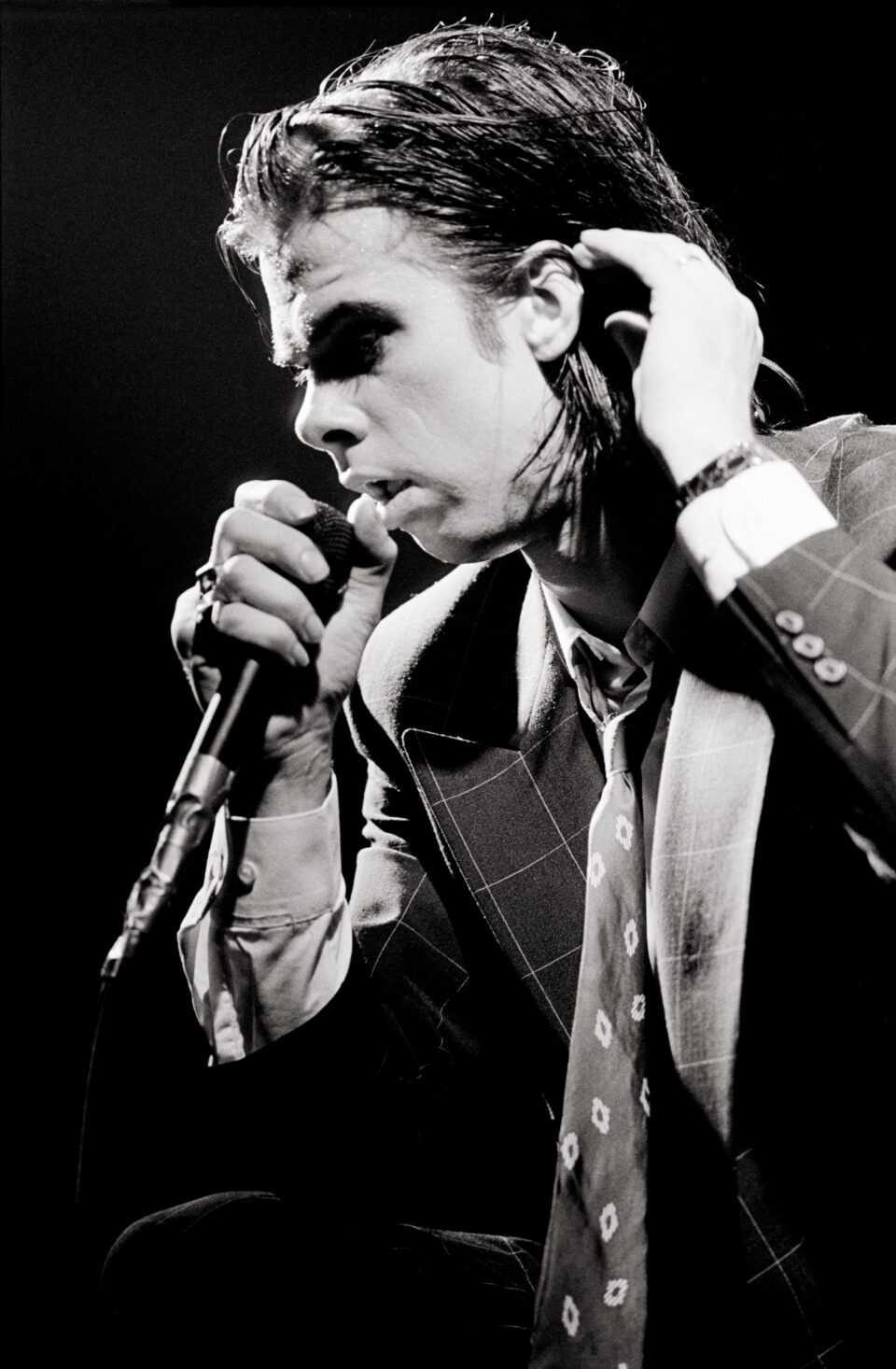

Jane’s Addiction’s audience grew rapidly, however, by 1987 hundreds of fans were lining up at Scream to see them. Started in 1985 on Monday nights at the Seven Seas nightclub in Hollywood, Scream ushered in the rise of goth and alt-rock, offering a distinct alternative to the corporate rock clubs. As crowds grew, Scream moved to the Hollywood Athletic Club, then the Embassy Hotel in downtown Los Angeles, and finally the Park Plaza Hotel in the Wilshire District, with thousands of clubgoers packing the venue weekly for the likes of Nick Cave, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Sisters of Mercy, and Faith No More, among others.

Nick Cave, The Scream, 1989 / photo by Greg Allen

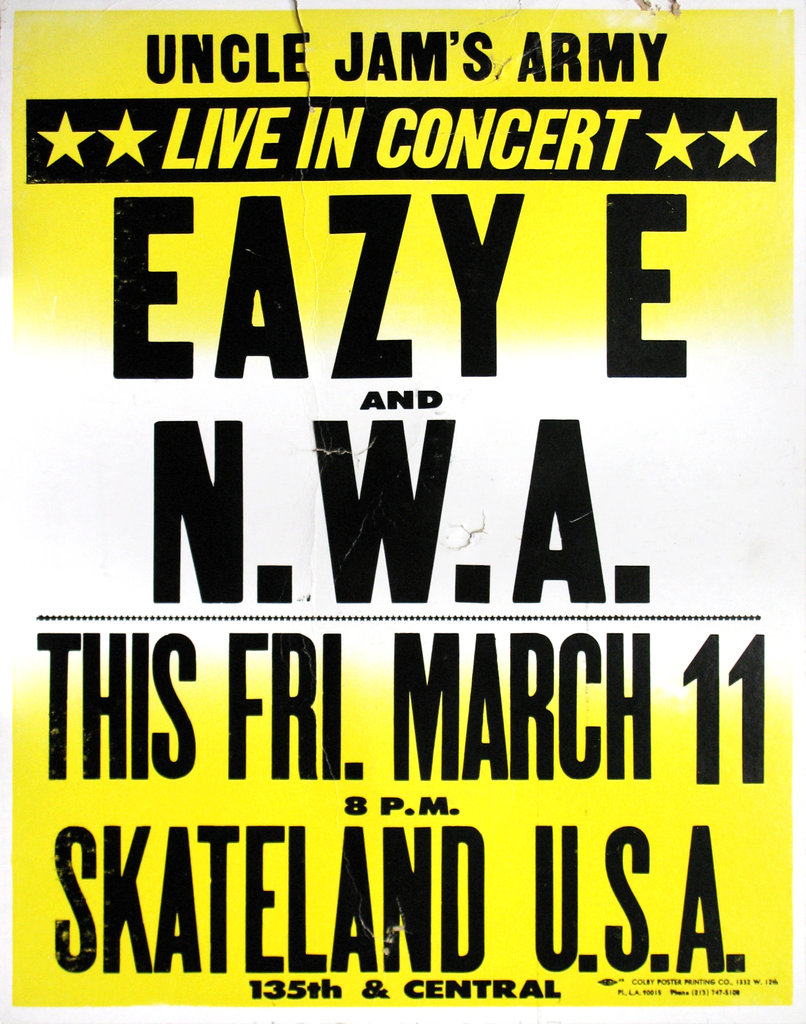

The late-’80s also saw the explosion of the Los Angeles hip-hop scene, with Ice-T and N.W.A putting Compton and South Central on the map for the rest of the world. While rock-oriented clubs around town shied away from booking rap artists, an unlikely roller rink in Compton became an influential early home for hip-hop. Dubbed Skateland U.S.A., the former bowling alley converted into a roller rink/music venue hosted Dr. Dre, Ice Cube and Eazy-E’s first concert together as N.W.A, as well as shows by Eric B. & Rakim, Mixmaster Spade, and Queen Latifah.

1990s

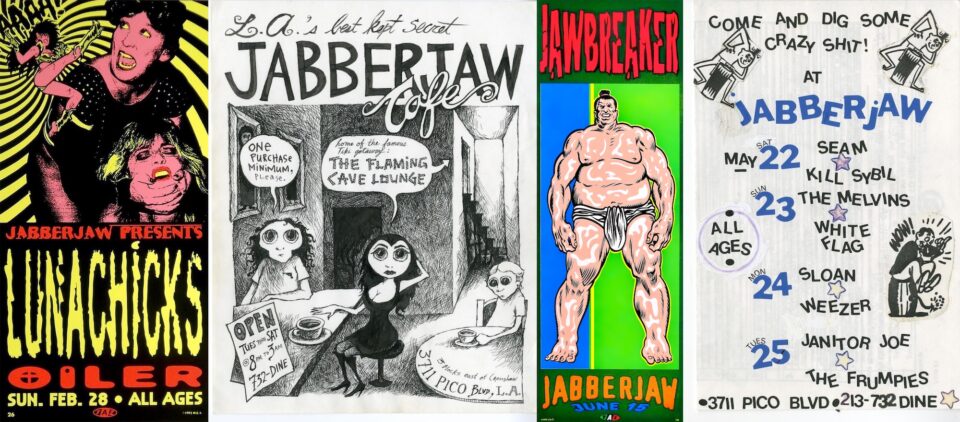

As the shift was happening from hair metal to grunge in rock music, Los Angeles was riding both waves. There were crossover venues such as the Dragonfly, Bar Deluxe, and Club Lingerie, but the sound was moving from Guns n’ Roses and Ratt to Beck and L7. Jabberjaw, an all-ages club that ran from 1989 to 1997 on a seedy and deserted stretch of Pico Boulevard in Arlington Heights, was one of the seminal underground venues of this era, regularly hosting riot grrrl bands and high-energy indie acts like Jawbreaker, Urge Overkill, The Make-Up, and Brainiac. According to Turcotte, Jabberjaw had “no legal anything, they always got busted by the city for never having permits.”

“It wasn’t about money, it wasn’t about fame, everybody just wanted to be creative back then,” remembers photographer Piper Ferguson, who co-hosted an indie dance night, Café Blue, at several venues in the mid- to late-’90s. “It was just about being around cool bands, cool friends, cool people, and community. We were part of a nerdy subculture that we loved. We felt grateful to be around the people and be around the experience. Getting to know bands and run a club and take pictures, I felt like I hit the jackpot.”

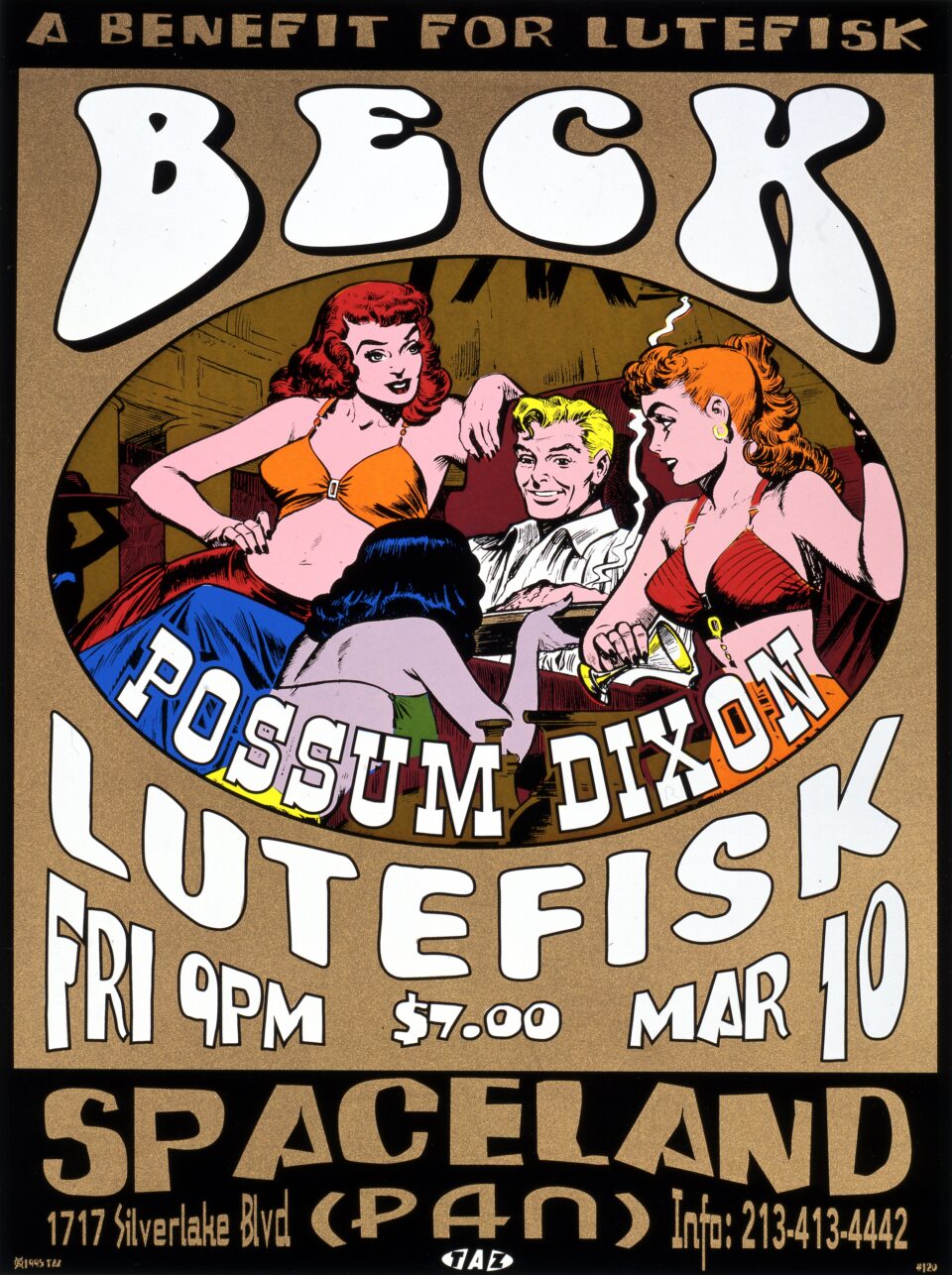

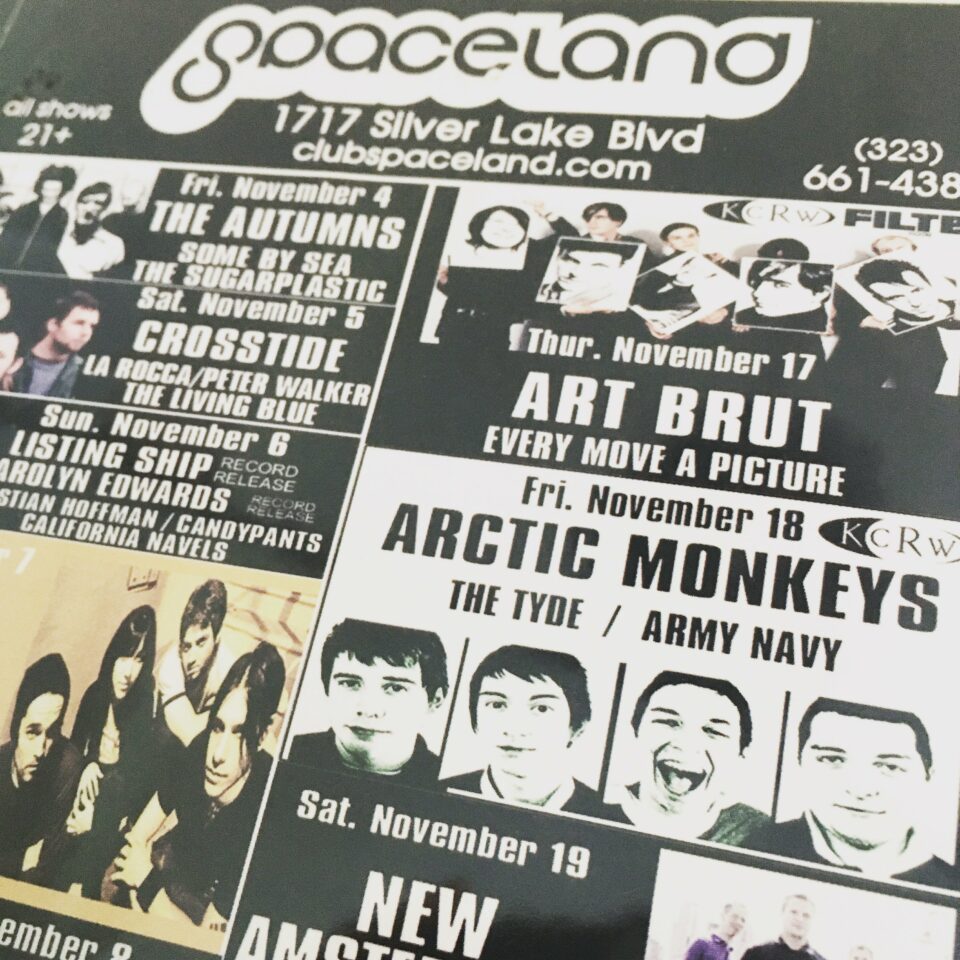

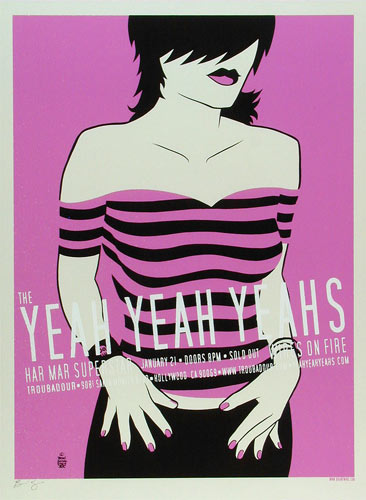

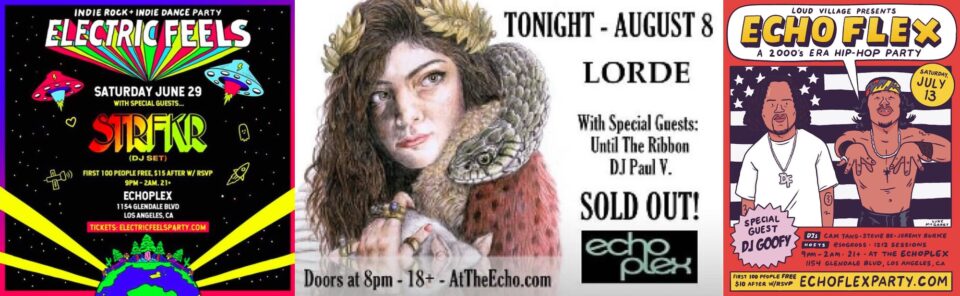

The 1990s was also the decade when LA’s Eastside became a nightclub destination, first with Spaceland, and later when Spaceland Productions opened The Echo in 2001—and even later, the adjacent Echoplex—as well as the Bootleg Theater and Silver Lake Lounge all drawing music lovers from across the city.

“A lot of the bands lived in the neighborhood, because that was when Silver Lake was affordable,” says Liz Garo, who was the talent buyer at the time for Spaceland Productions. “That was really Mitchell Frank’s impetus for starting the venue. He had friends in bands and they needed a place to play. The musicians were part of the neighborhood, and the venue became the meeting grounwhere other things developed as a ripple effect, like collaborations and ideas.”

“Venues bring in a culture and community that gives a neighborhood a different kind of heartbeat than other businesses do." —Liz Garo, talent booker

Poster art by Jim Evans a.k.a. TAZ

Garo points out that independent nightclubs often bring life to urban neighborhoods that are ignored and/or considered unsafe. From the presence of nightclubs come bars, then cafes and coffee spots, then restaurants; then the real estate starts looking desirable, while still being affordable—for the time being—and development snowballs from there. This was certainly witnessed firsthand in Silver Lake and Echo Park, the neighborhoods that housed Spaceland and continue to serve as home to The Echo and the Echoplex.

“Venues bring in a culture and community that gives a neighborhood a different kind of heartbeat than other businesses do,” says Garo. “People don't buy property because a new nail salon opened up. A music venue has so much attached to it. It helps bring people to a neighborhood and changes it and increases property value.”

2000s

“People were always talking about the early 2000s New York indie rock scene as if it were as good as it was in the ’70s with CBGB,” says Ferguson. “There was so much happening in LA [at the time], but it didn't get any recognition. There were so many amazing bands playing all the clubs in LA every single night of the week, drawing hundreds of people, filling clubs like Spaceland and The Echo. That movement was happening before the New York indie rock scene, and felt equally as important.”

The Eastside started to look different by the mid-2000s, and with it, its demographics. Says Garo, “There's always the initial scene: the weirdos, the musicians, the artists. They're not going to care if the bathrooms are not perfect. They're more about the experience and wanting to be part of that community. That builds and people start talking about that place, and then there's the curious who want to come see it, and then it goes mainstream. Spaceland gets sold to Live Nation and it changes the vibe.”

"There were so many amazing bands playing all the clubs in LA every single night of the week. That movement was happening before the New York indie rock scene, and felt equally as important.” —Piper Ferguson, photographer

As time passes, the city’s scenes and neighborhoods begin to disperse, and with them, the musicians who are associated with particular venues. A band that could sell out the Troubadour draws 100 people to an Eastside venue and vice versa, because fans don’t drive across town for a gig anymore, not like they used to in the ’80s and even the ’90s.

When the business plan for the 300-capacity Echo was being put together in the 2000s, the concept of the 700-capacity Echoplex was also put into place as a growth step for musicians that the former cultivated. From there they would move to The Regent in DTLA and the Natural History Museum, all booked by Spaceland Presents, what Garo refers to as “a pipeline to develop talent.”

At all-ages venues (which are few and far between in Los Angeles) like The Smell, artists like Ty Segall and Surf Curse were getting their first tastes of live gigs. Says Segall, “What’s so cool about The Smell is that it’s really inclusive and it’s all different kinds of music. I saw so many bands there, like No Age and Mika Miko. That was when I got exposed to every different type of weird version of outside punk, rock, noise, freaky stuff. It was definitely very influential for my 16-year-old mind.”

Nick Zinner, Har Mar Superstar, and Steve Aoki at The Echo / photo by Piper Ferguson

2010-2020s

In Henderson, Nevada, teenagers Nick Rattigan and Jacob Rubeck of Surf Curse were finding music through the internet, as there was no place like The Smell in their hometown. They watched a performance of No Age at that venue online and through that, discovered a whole host of other bands. They finally made their way to The Smell when they were 18, catching Future Islands and Lower Dens, among many other bands.

“That was the most impactful thing for us,” the duo says. “It was our first experience of an all-ages space. We didn’t even know things like that existed. It was our first punk show where people were marching around. It's so important to experience that when you're young. That’s when it feels like true magic. You have no knowledge about how they make music. You just know that you feel something from it in the live realm. You’re sonically transformed. It's the most important thing in your youth. We were like, ‘We have to play this venue.’”

Surf Curse performed at The Smell while they were still Nevada residents. Their first show was sparsely attended, their second was sold out. On their way to that show, they got into a car accident where Rattigan’s face was smashed and bleeding, his drum kit scattered all over the place, but they still made it to the gig.

“Teenagers were hauling my drum set and setting it up for me,” remembers Rattigan. “I had so much adrenaline from the crash and I was ready to go. People were bouncing off the walls and it was just crazy. We were going so hard. They were going so hard. It was like a spiritual experience. After that our Bandcamp just kept running out of downloads and that was the first big explosion of our music.”

“People were bouncing off the walls (at The Smell) and it was just crazy. We were going so hard. They were going so hard. It was like a spiritual experience." —Nick Rattigan, Surf Curse

The duo’s trajectory has been on a major upswing since those early shows at The Smell, but it’s a priority for them to have all-ages shows whenever and wherever possible. “We want to play for the people who really want to see us, which is young people. There’s such a strange desperation that's always drawn us to places like The Smell. We don't want to neglect that memory or that moment for someone the same way we had it—or didn’t have it—when we were young.”

The now-defunct Bootleg Theater, which had both an all-ages section and a 21+ section, is another Eastside haven that holds memories for Surf Curse. “They were booking fantastic shows,” they say. “We only played there once, and both did solo shows there, but even if it’s just one time, it’s still a venue that you would go to when you were younger where you saw someone you loved play, and you can’t believe you’re on the same stage as them.”

Run the Jewels, Echoplex / photo by Misha Vladimirskiy

The El Rey Theater on Wilshire Boulevard is likewise special for LA rapper KYLE—a.k.a. SuperDuperKyle—who says, “When you see an artist at the El Rey, they're already exploding, but it's on this really small scale where you still get a very intimate experience with them. Every artist that I've watched at the El Rey, I remember that show of theirs better than all their other shows. I played there too, and it was my favorite of my shows. When you're a small artist, you're dreaming about a sea of people listening to your music. The El Rey is the first dose of that any artist gets. When it’s packed, it gives you a feeling other venues don't give you.”

Back up on the Sunset Strip, the Whisky still occupies the same original footprint, but now offers VIP packages upwards of $150 without a significant bang for your buck. “The aura of the place has changed,” says Echols. “Instead of having top-tier musicians with albums in the charts, they have beginners without much of a following that will pay the club to play rather than the other way around. It wouldn’t have survived, and we couldn’t have survived doing that.”

The one thing Los Angeles’ independent music venues never had to survive before 2020 was a pandemic—but thankfully, most of them have thus far been able to weather many challenges presented by COVID-19. The international community of music lovers and the local community in their neighborhoods have rallied behind these longstanding institutions, supporting the spaces and their staff, enabling them to remain standing and operational. Local music venues continue to be a cornerstone of LA culture, whose influence still impacts the entire globe. FL