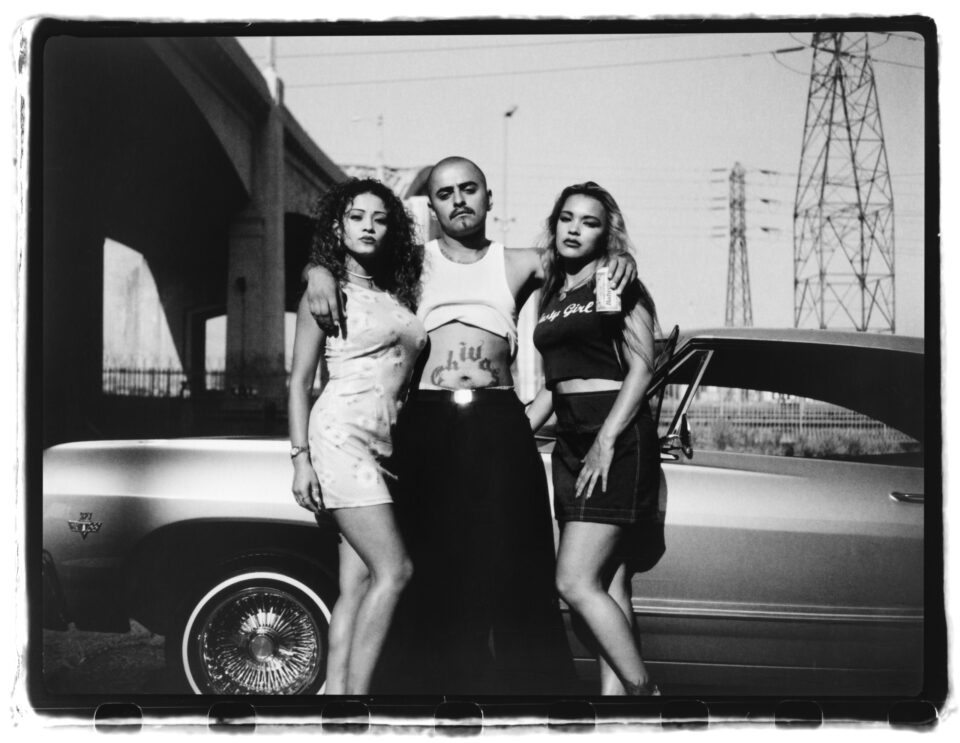

At the VIP opening on Thursday for the Hip Hop Til Infinity exhibition in Los Angeles, photographer Estevan Oriol could see echoes from his life and culture all around him. Blown up on a wall was his portrait of Ice Cube, scowling in a black LA Dodgers cap, the fingers on his left hand shaped into a “W” to represent “Westside” pride for the iconic West Coast rapper. There were also pictures by Oriol of Nipsey Hussle, House of Pain, and Cypress Hill, along with artifacts from low rider and Chicano culture.

An entire wall was filled with paños—handkerchiefs covered in meticulous artwork drawn in prison. Each represented the art “that all my homies would send me from prison,” says Oriol, and were displayed here behind glass frames. The intensely personal artwork is from a tradition that goes back to the 1940s, and it’s sometimes even used as currency behind prison walls. “It's just, this [is] my life,” Oriel says with quiet pride. “The hip-hop wall, low riding.”

Images of Nipsey Hussle (left) and Ice Cube (right) in Estaban Oriol’s section of the Hip Hop Til Infinity exhibition in Los Angeles.

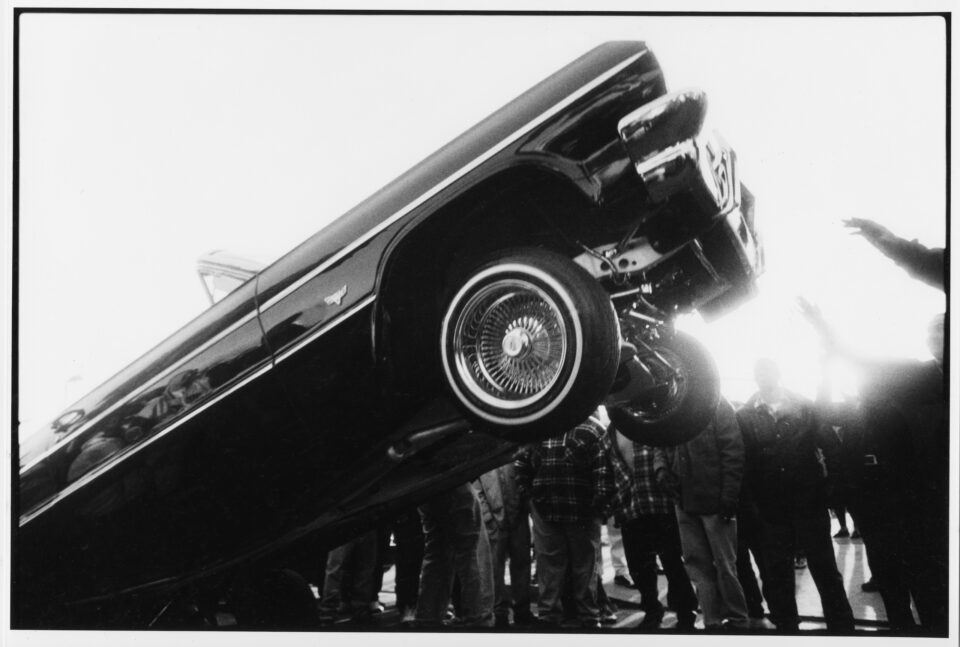

Photos by Estevan Oriol

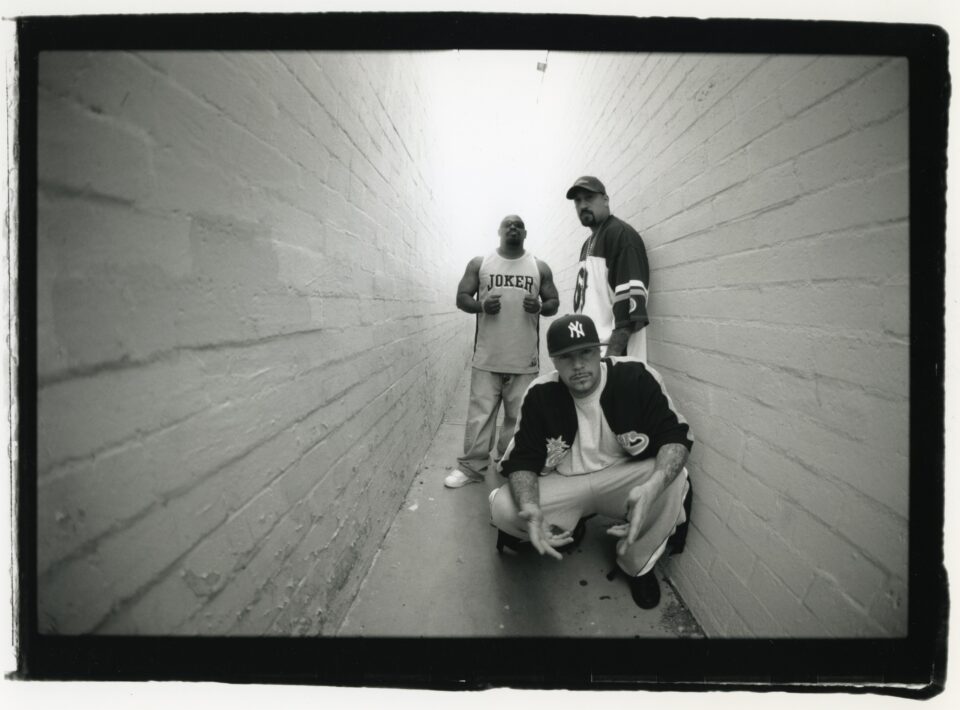

Cypress Hill / Photo by Estevan Oriol

The photographer was given his own corner room of Hip Hop Til Infinity, an immersive exhibition of art and culture from 50 years of rap music which will remain open to the public through March 18. The LA show is a new version of an exhibition that debuted last year in the ornate Hall des Lumières in Lower Manhattan, spearheaded by Mass Appeal CEO Peter Bittenbender. Organizers call the exhibit a “visual mixtape,” with interactive displays along with live DJs, photography galleries, clothing, magazine covers, and other markers from a vibrant musical history.

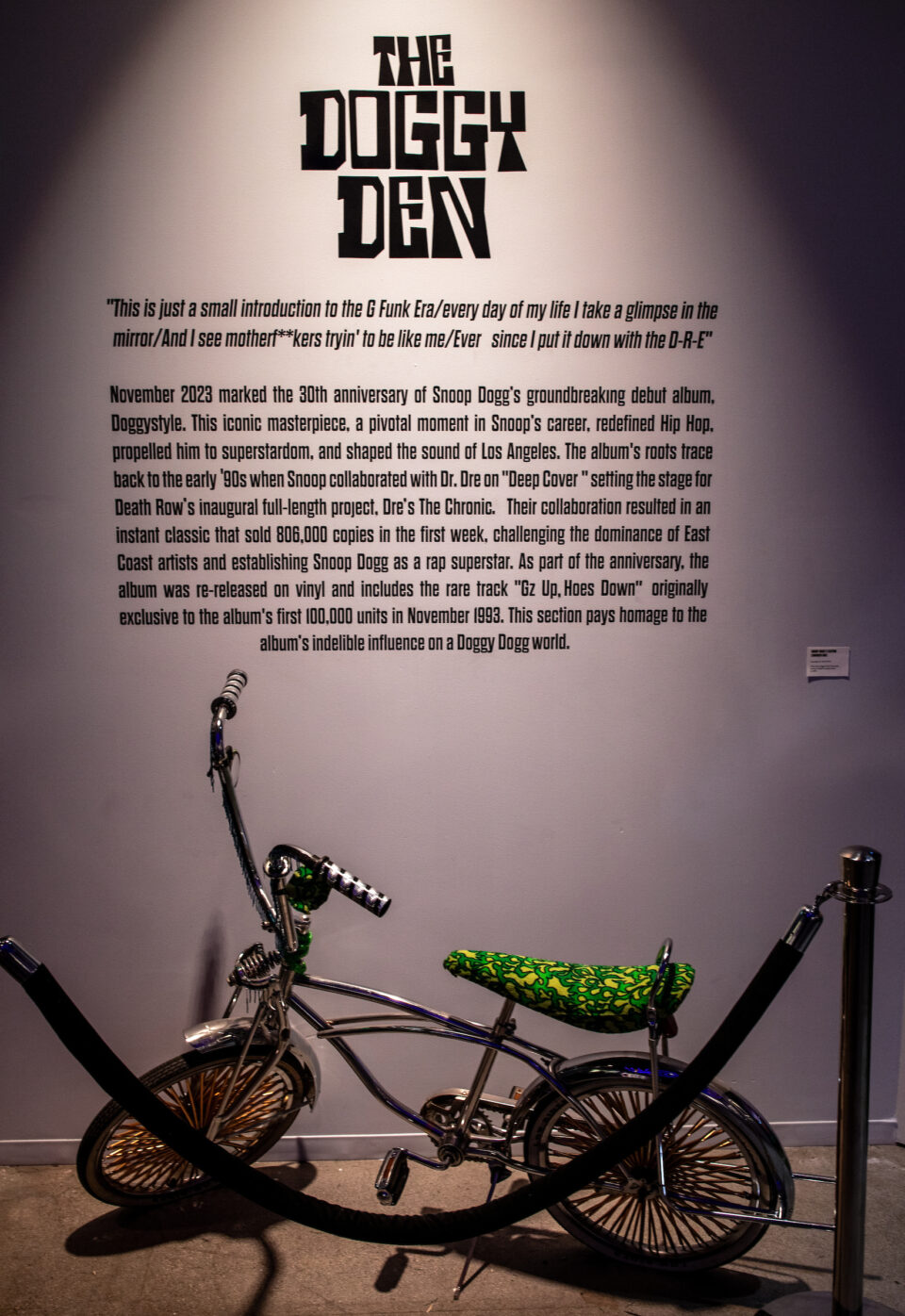

In one room, there’s a life-sized recreation of the Death Row Records logo where fans can sit for grim snapshots on the executioner’s chair. There are boomboxes and turntables, platinum records and GRAMMY Awards, backstage passes and vintage mixtapes. Another room called “The Doggy Den” was curated personally by Snoop Dogg, where visitors can step into the cover art of Doggstyle, his 1993 debut studio album, then put on headphones to remix songs on a console, adding or subtracting bass, beats, or vocals. In the exhibition’s largest room, a program of moving pictures and music tells the story of hip-hop through the generations, with images projected on four walls.

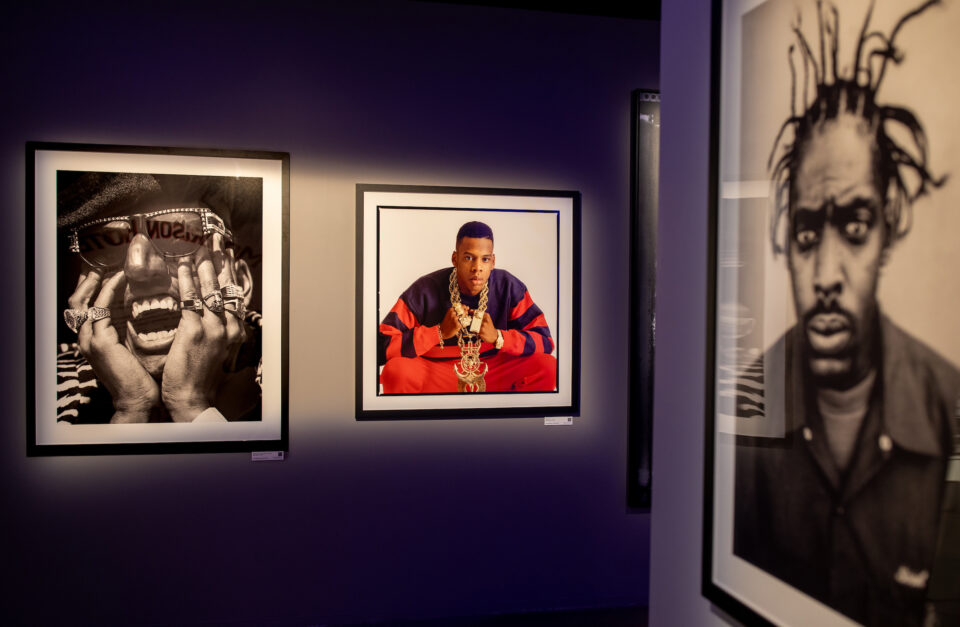

Pictures of Shock G, Jay-Z and Coolio on the walls of the Hip Hop Til Infinity exhibition in Los Angeles.

A wall of cannabis during the multimedia presentation in the big room at the Hip Hop Til Infinity exhibition in Los Angeles.

Hip Hop Til Infinity is set up in the former location of the massive Amoeba Records store on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood (now called Lighthouse Immersive Los Angeles). Unsurprisingly, the LA version of the show emphasizes the West Coast’s distinctive contributions to the genre. “New York's known for that grimy, underground hip-hop, those hardcore beats. And we're known for the gangsta rap,” Oriol says. “We had to go hard and do something different, because back in the ’80s and ’90, it was bad if you did something like somebody else. So you always had to dress different, always had to set yourself aside. You always had to make your own thing.”

As he speaks, Oriol stands near a small glass case with a bit of his personal history inside: his old Minolta SRT SC-II, the film camera that got him started shooting pictures. The camera was a gift from his father while Oriol was still a tour manager for House of Pain and Cypress Hill. At the time, he said, “I had no intentions of being a photographer.” His only photography education was his dad showing him how the camera meter worked. Oriol figured out the rest himself as he brought the camera on the road, capturing moments with some of the most compelling names in rap music.

Photo by Estevan Oriol

“New York’s known for that grimy, underground hip-hop, those hardcore beats. And we’re known for the gangsta rap. We had to go hard and do something different.” — Estevan Oriol

At home, he turned the lens toward his local community—all the cars, tattoos, pitbulls, and urban landscapes. It turned out he was a naturally gifted visual artist, finding a distinctive style and vision that captured the culture where music intersected with life at street level. It was 13 years later, after Oriol left the touring life, that photography became his main activity. “I wasn't on tour no more, and I was like, ‘What am I gonna do?’ Well, the only thing I could do is construction and take pictures. So I was like, let me get give this a shot.”

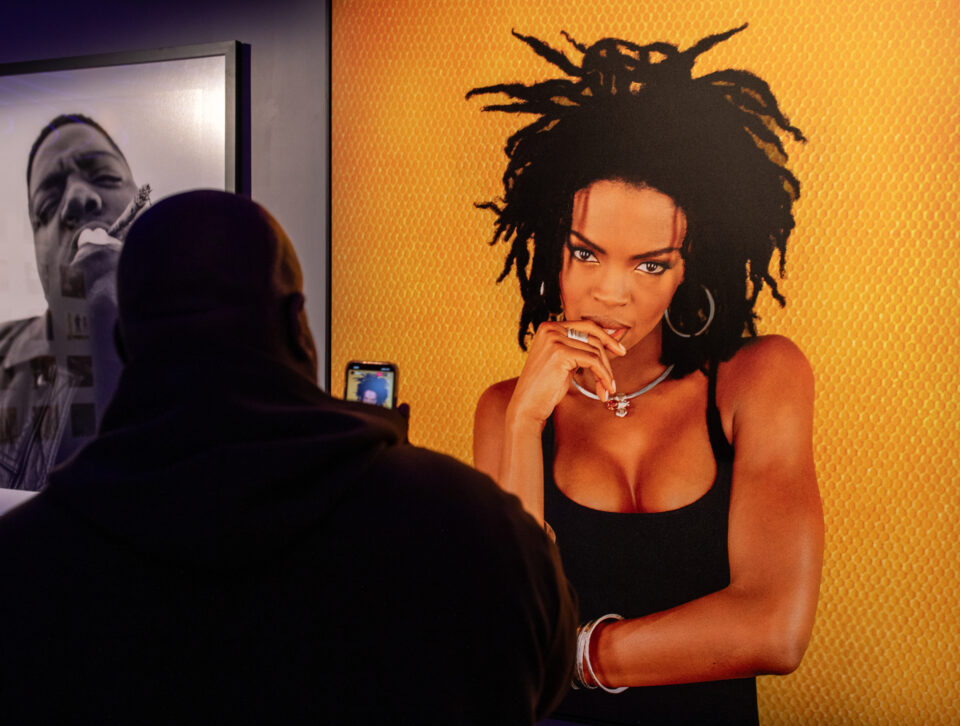

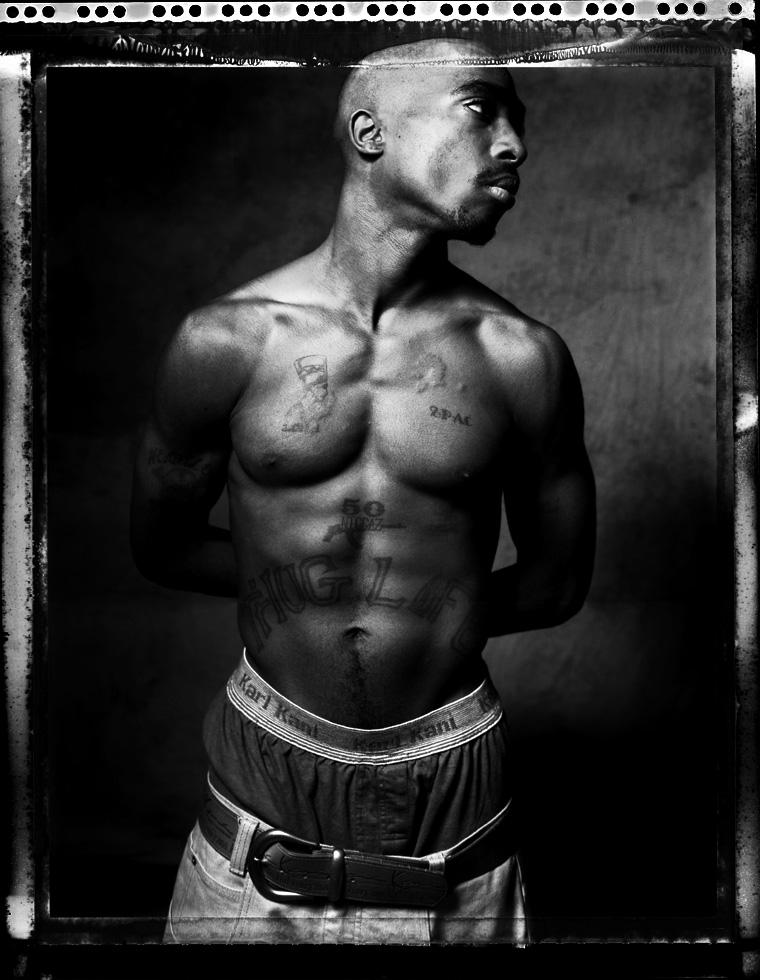

For its exhibition’s LA edition, Mass Appeal teamed up with the Morrison Hotel Gallery to add a vibrant selection of classic hip-hop portraiture, printed for the show at a massive scale. The result is a selection of large-scale photographs from the Bronx in the 1980s to Los Angeles in the 1990s and right up to the present. There are portraits of Tupac Shakur, N.W.A, Kendrick Lamar, Beastie Boys, Coolio, DMX, Lauryn Hill, Queen Latifah, OutKast, and many more.

“The beauty of the genre of hip-hop is that things got colorful, things got fun. It actually bred a whole other breed of photographer,” says Timothy White, a veteran portrait photographer for multiple genres, and a longtime partner-owner of Morrison Hotel (with fellow music photog Henry Diltz) until its recent sale. “The genre itself is so special in the history of music, but it's also this new wave of photographers.”

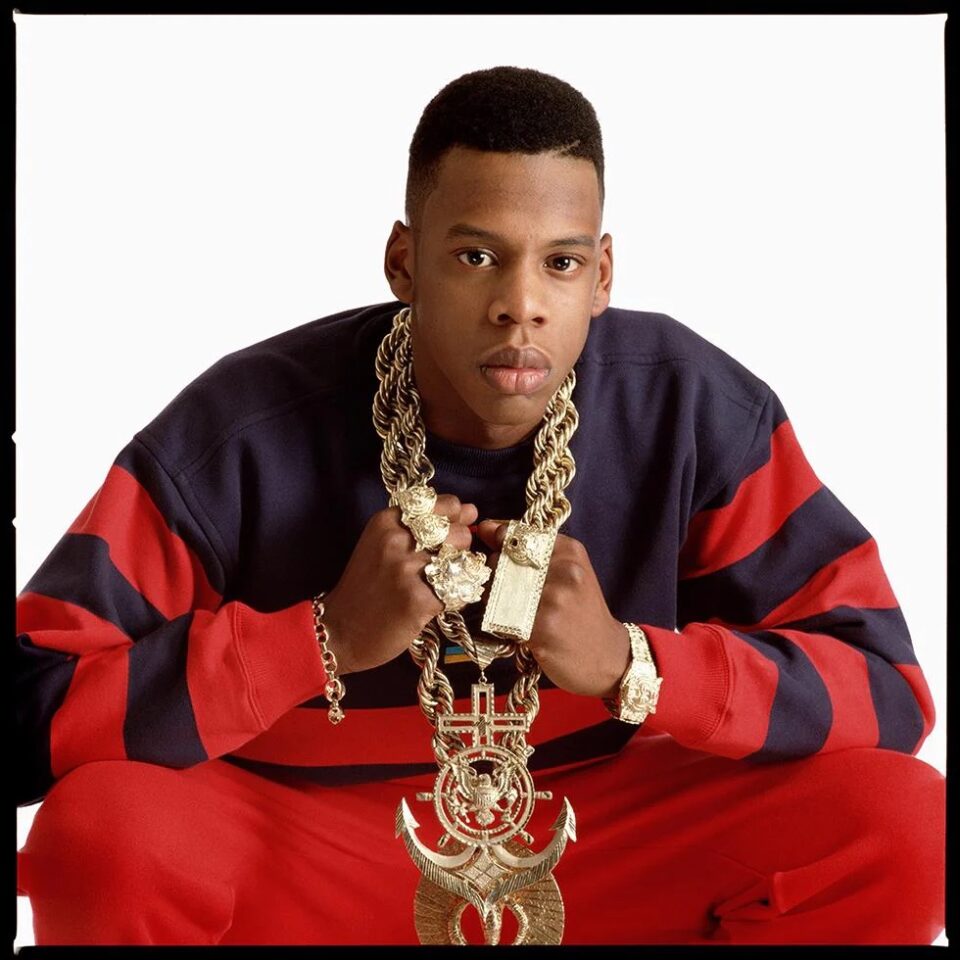

White has four pictures hanging in the show, including one of his very first hip-hop subjects: a very young JAY-Z in 1988. The future superstar rapper is shown wearing a red and purple track suit along with heavy gold chains and medallions. “He showed up like that for his friend's shoot," White recalls. “I saw him and I was like, ‘I gotta shoot this guy.’ You could just feel it. It was happening. He was destined for sure.”

Jay-Z / Photo by Timothy White (courtesy Morrison Hotel Gallery)

Tupac / Photo by Geoffroy de Boismenu (courtesy Morrison Hotel Gallery)

Big Daddy Kane / Photo by Catherine McGann (courtesy Morrison Hotel Gallery)

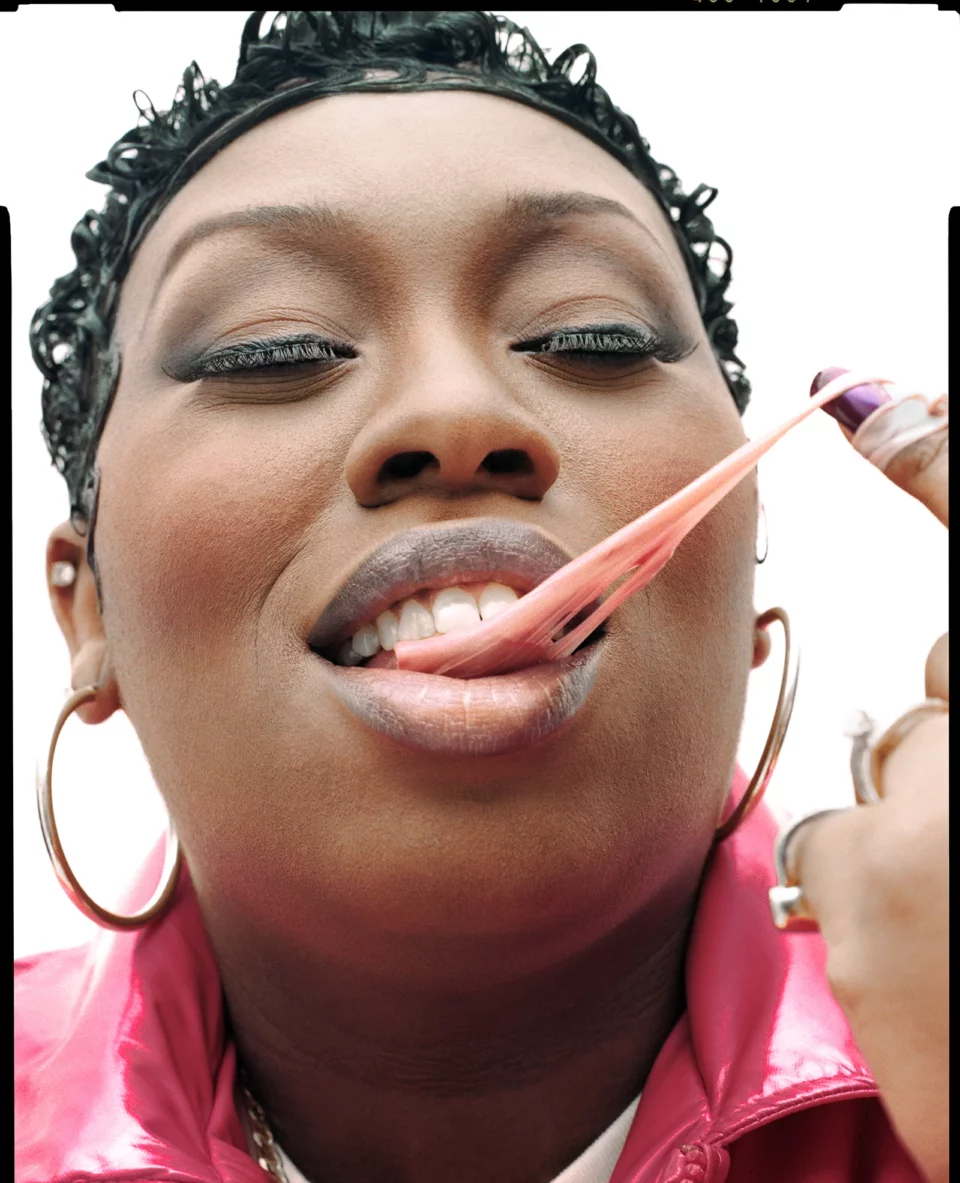

Missy Elliott / Photo by Christian Witkin (courtesy Morrison Hotel Gallery)

Outkast / Photo by Jonathan Mannion (courtesy Morrison Hotel Gallery)

“Hip-hop is today's pop music,” says Adam Block, CEO of the Morrison Hotel Gallery, which has locations in Los Angeles and New York. “Part of the beauty of music today is that a lot of people listening to music aren't thinking about whether it's older or new. They’re just thinking about if it’s good or not. And a lot of these artists speak to kids today the [same] way they spoke to us when it was released originally.”

In the room dedicated to the Morrison Hotel Gallery photographers—including Danny Clinch, Jonathan Mannion, Christian Witkin, and Travis Shinn—the show’s prints are for sale, as are versions of different sizes offered by Morrison Hotel. After making this second stop in LA, organizers aim to see the show travel further. “The hope and intention is for it to do well enough that there's demand to move it,” says Block. “Obviously, Morrison Hotel Gallery would be delighted to move some or all of this to another market. It's a pretty great experience if you’re a fan of the genre.” FL

Nipsey’s Hussle’s 2020 Grammy Award on display in the Hip Hop Til Infinity exhibition in Los Angeles, called “The Doggy Den.”