It all began with cassette tapes. When Daniel Johnston first started writing and recording his music in the early ’80s, he did so on a $60 Sanyo mono boombox, handing out copies for free—complete with his distinctive hand-drawn covers—to friends and strangers, including customers at the McDonald’s where he worked (and even Richard Linklater in a scene from the director’s debut feature). Legend has it that, at the beginning, he had no means of copying his tapes, and would actually re-record them each time, meaning that each original copy out there is unique. Then, in 1986, Stress Records (now seemingly defunct) purchased Johnston’s back catalog and the distribution of standardized versions of his albums began. Even today, you can still buy replicas of all the tapes at the site Hi, How Are You, which is run by The Daniel Johnston Trust.

Johnston—who had bipolar disorder and spent years in and out of psychiatric institutions before passing away in 2019—would soon become a leading figure in underground/outsider music. Though partly thanks to the wider distribution of his tapes and partly due to becoming well-known within the Austin music scene once he moved there (he also found his way into Linklater’s 1985 documentary short Woodshock documenting a local Austin music fest, where he can be seen hawking tapes), most of it probably came from the super-fandom of Kurt Cobain, who was often seen wearing a T-shirt with the iconic artwork of Johnston’s Hi, How Are You? album. Johnston’s profile rose steadily—his 1994 album Fun was even released on Atlantic Records, though the major label dropped him two years later. After that, his recording prowess slowed down some. Between 1980 and 1988, he’d released a vast slew of recorded material, but then really only a smattering afterward, even as his profile continued to rise.

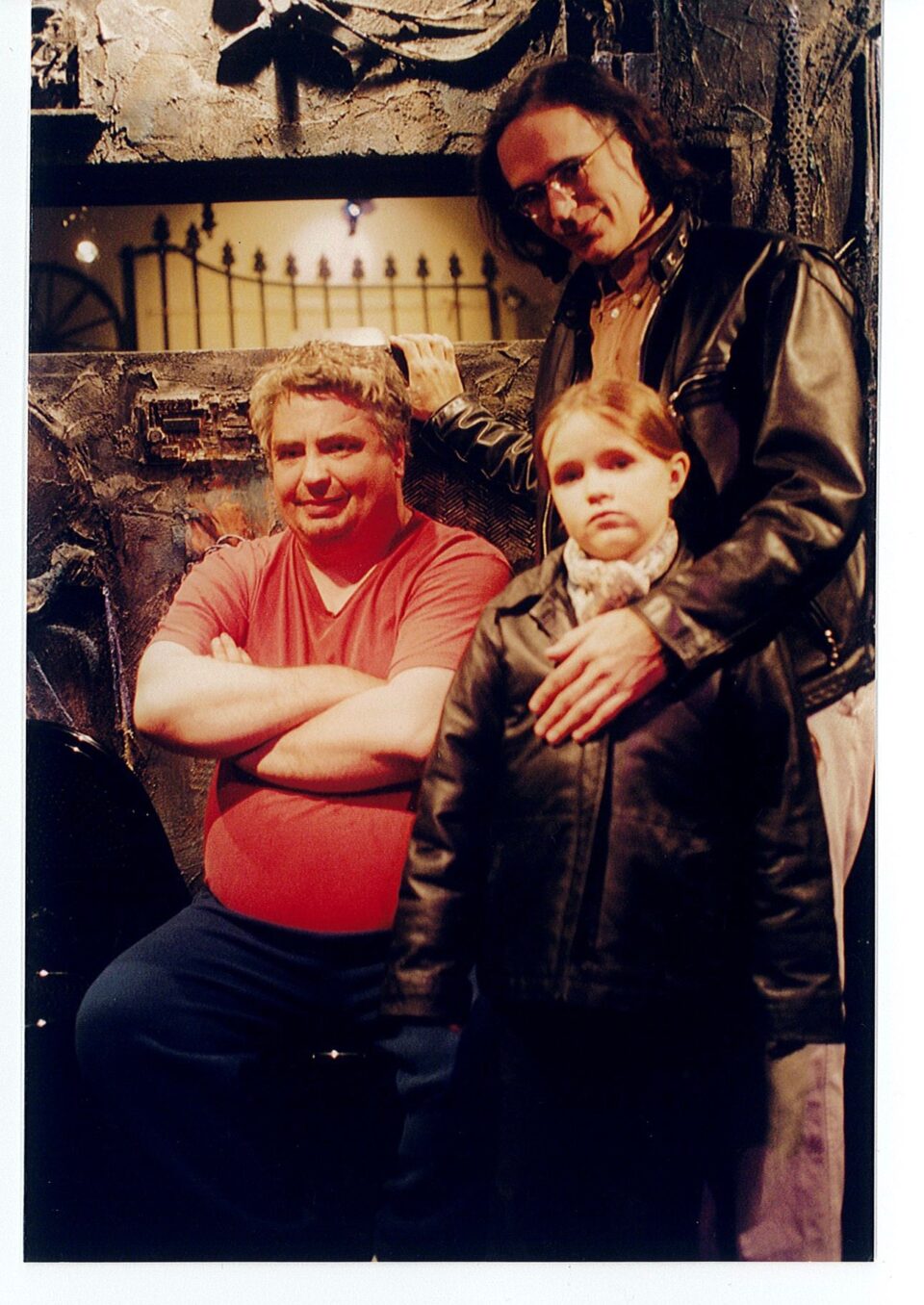

Daniel Johnston and Kramer / Photo by Don Goede

Others, however, continued to record his songs up to and beyond his death. Kathy McCarty’s stunning version of “Living Life” over the end credits of Linklater’s Before Sunrise was how I first came across Johnston. It was also on Dead Dog’s Eyeball, her 1996 tribute album to Johnston that was re-released a couple of years ago, and remains one of my favorite recordings. Eels also covered that song for 2004’s tribute record The Late Great Daniel Johnston: Discovered Covered. Despite its title, it was recorded 15 years before Johnston’s death, and comprised one disc of covers and one of the original versions. Included on the former is Bright Eyes’ stunning take on “Devil Town” as well as interpretations by Teenage Fanclub, TV on the Radio, Death Cab for Cutie, Mercury Rev, Beck, Tom Waits, Vic Chesnutt, and more. In 2020, Built to Spill released their own tribute album, and he’s also been covered by Wilco, The Dead Milkmen, Lana Del Rey, Beach House, and Karen O.

All the cover versions, of course, are more accessible than the originals. For while Daniel Johnston could write the most incredible songs, his raw delivery and lo-fi recordings—especially on those early releases—are probably too abrasive for many. Years later, when performing live, his arms shaking from medication he was taking, his versions were mellowed down, if still rough around the edges, but the profundity and power of his songs was never diluted, nor was their childlike innocence. In another life, I had to review him live for a now-defunct magazine at the Union Chapel in Islington, London in 2007—a gig that was captured on film and released on DVD as The Angel and Daniel Johnston (a play on the title of the 2005 documentary The Devil and Daniel Johnston) the following year. My word count was short, but my editor wrote back to say “Your first line is enough. I’m cutting the rest.” And so, this was all that was printed for that review: “As long as Daniel Johnston is alive, there is no need for God.”

Daniel Johnston, Kramer, and Tess at the Knitting Factory, 1999 / Photo by Valerie Zars

That’s precisely why the rawness of those early recordings is so powerful—they are him, utterly unfiltered, as he always was, only brought into a digital age for more people to discover him, connect with him, find solace in his world.

Of course, that’s when he was still alive. Now, over four years after his death, he’s being reborn for the digital age—all those early recordings have been remastered by Kramer (who produced 1990’s 1990) and made available on Bandcamp as part of a release series called Daniel Johnston in the 20th Century. They’re the ones that best capture the inelegant yet magnificent beauty of Johnston’s compositions, and as such serve as a striking historical document of an influential figure in modern music. Whether fixated on his obsessive, life-long unrequited love for his friend-but-never-lover Laurie Allen, his strict religious beliefs, fictional characters, or just a haunting, abject, existential loneliness and longing, his songs depict a man who never really stopped being a child—and who will forever sound like one—despite the tormented, troubled adult life he led. That’s precisely why the rawness of those early recordings is so powerful—they are him, utterly unfiltered, as he always was, only brought into a digital age for more people to discover him, connect with him, find solace in his world. It is, of course, important to not romanticize his mental disorders, but they should be acknowledged, because they were responsible for who he was and the songs he made.

As of last week, Kramer’s Shimmy-Disc has shared two new live albums—one in New York, one in Berlin, both recorded in 2000—on Johnston’s Bandcamp page (the former is also available in physical formats—including, of course, cassette), and a plan for another release series called Daniel Johnston in the 21st Century, which will issue a further 12 albums on a monthly basis throughout 2024. Ironically, at the time of writing, Bandcamp went down briefly, which surely has nothing to do with the company laying off half of its staff after being bought out by Songtradr. Perhaps it’s better to stick with the cassettes, after all. Besides, nothing probably would have made Johnston happier. FL