It was a gentle clash of cultures at Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, a balance between the casually bohemian and the elegantly avant-garde, as a crowd arrived for the US premiere of a new opera called Last Days. There were attendants dressed in formal chic for a night at the opera, and others in hoodies and jeans, looking more like grunge fans ready to rock. What they all shared on this night in February was simple and still jarring: thoughts about the death of Kurt Cobain.

In the audience was Gus Van Sant, writer and director of the 2005 film of the same name the show was based on, an impressionistic imagining of the hours leading to Cobain’s suicide on April 5, 1994, translated into a fictional character named Blake. Also in attendance was Kim Gordon, formerly of Sonic Youth, a friend of Cobain’s who had a small but meaningful role in the film as a concerned record company exec urging Blake to leave his house in the woods and escape his detachment and despair.

These are still the early days for the opera. Created by a pair of young British artists, composer Oliver Leith and librettist Matt Copson, Last Days was first performed during a four-date run last fall in London at the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Theatre, followed by the single LA performance, with additional cities yet to be announced. More immediate is last week’s album release of the 95-minute opera’s UK production on the Platoon label. The 26 songs of Last Days were recorded with the strings of 12 Ensemble along with piano and percussion from the GBSR Duo.

There are no Nirvana songs—or any rock songs, for that matter—but the strings in Leith’s music are frequently evocative of the raw feelings and distortion of the era’s alt-rock sound. “That’s basically how my music sounds anyway,” says Leith, a composer of classical and electronic music. “But if I think back to the sort of things I liked—I listened to a lot of grunge when I was younger, even though it was sort of over by the time I was fully into music.” The music in Last Days, he adds, has a kind of “hazy tuning—‘thick air’ is what I call it, where the notes collide with each other a little more.”

“This could easily be a Greek god who commits suicide... It couldn’t be more operatic, in a way.” — Oliver Leith

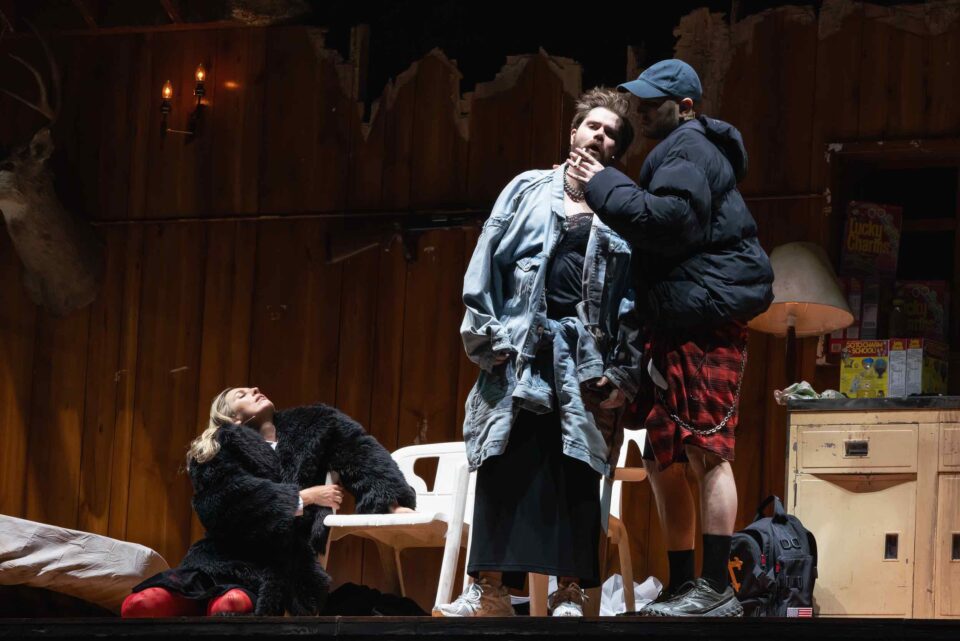

Onstage, and like the film, Last Days follows Blake as he meanders around the house, increasingly detached from his life as a rock star, avoiding most human contact around him. A shotgun is prominently displayed in the house, though the audience never sees (or hears) a gunshot, which otherwise echoes the slow-motion tragedy of Cobain’s death. “This could easily be a Greek god who commits suicide,” Leith says of this atypical opera material. “The baseline is almost the same. The only thing is, it’s not a dramatic plot point. It’s just the end. So it couldn’t be more operatic, in a way.”

Three decades after the Nirvana leader’s suicide at 27 at the height of his fame, it’s a story that still resonates—and Last Days is just one interpretation of it. “We want to expand it in various ways, in different formats, and to reach an audience of people who I think will engage with it,” explains Copson, who co-directed the performances in London and LA. “It’ll be really interesting to see how it shifts and changes over time.”

At the center of the opera is Blake, the Cobain doppelgänger played by French actress Agathe Rousselle, in tangled blonde hair, an oversized furry green coat, and white-framed sunglasses immediately recognizable as an outfit of high-grunge (the show’s retro costumes were designed by Balenciaga). Rousselle doesn’t sing in the show and hardly has any spoken dialogue other than distracted mumbles, much like Van Sant’s Blake in the film, as played by Michael Pitt.

Ahead of the London premiere, the director had seen Julia Ducournau’s 2021 hallucinogenic body-horror film Titane, featuring Rousselle in her first feature film role. “It had a kind of animalistic, feral quality to her performance that I was extremely struck by,” Copson explains, “knowing the character that I was interested in her playing had no voice and everything had to be expressed through movement itself—like a scared cat, essentially. She just struck me as the one, and it was really more about the glasses and the hair being the symbols that we needed. I don’t think you really pay attention or notice her gender within the role.”

“[Agathe Rousselle] just struck me as the one, and it was really more about the glasses and the hair being the symbols that we needed. I don’t think you really pay attention or notice her gender within the role.” — Matt Copson

Days ahead of the LA performance, the Last Days company was preparing on a Burbank rehearsal stage. Most of the actors were in full costume, though it wasn’t officially a dress rehearsal. That’s because the opera couldn’t truly be performed without Blake’s furry green coat, which is both a flashback to the ’90s rock era and a layer of emotional armor as unwanted visitors arrive at the house. Even under the fluorescent lighting of the rehearsal space, the piece comes to life on a stage set designed to look like the inside of a rock star’s disheveled home in the woods. Copson sits beside Anna Morrisey, co-director of both the London and Los Angeles productions, while Leith watches from further back, consulting with Copson between scenes.

An especially moving moment occurs early on when Blake kneels beside a record player to spin a favorite album. In the opera, the song is “Non Voglio Mai Vedere Il Sole Tramontare” (translated as “I never want to see the sun go down”), a prerecorded aria sung in Italian by eclectic avant-pop singer Caroline Polachek. And during its four minutes, Blake is lost within the music, hands moving in the air, as the song ends with the lines: “Non ho mai amato così tanto la vita / Ho amato così tanto la vita / Non voglio che finisca” (“I have never loved life so much / I loved life so much / I don’t want it to end”).

At one point, Blake puts a hand on the record as it plays, slowing it down, distorting its rhythm and melody, deepening the voice of Polachek. “We imagine that this is Blake trying to reconnect to the music and remind himself that this is what it is,” says Leith. “It’s an important moment … of autonomy or control, because he also touches the record and it slows down. And this is the only time where he seems to be able to affect the outer world.”

In the opera’s second half, Blake is finally seen bent over an electric guitar, slowly strumming a chord (vaguely reminiscent of Nirvana’s mournful “Something in the Way”), as a superfan hiding in the kitchen sings the words from “Non Voglio Mai Vedere Il Sole Tramontare.” Throughout the opera, Blake is like a ghost in his own house. There are other people around, such as the assistant who calls himself Blake’s “understudy,” but who’s mostly there to party like the other hangers on. The only character looking to check up on Blake is a private investigator he’s never met. Young Mormons come proselytizing to the door. A frustrated DHL driver tries to deliver guitars. Another houseguest tries to give Blake a demo tape. Blake copes by crunching through a large bowl of sugary Lucky Charms.

“[Gus Van Sant] quite rightly said, ‘Just do what you want with it. That’s the best approach.’” — Matt Copson

The Last Days opera emerged after Copson and Leith were introduced in London. Copson, a visual artist, had no experience in opera, but they found that they shared certain interests. They began talking about a potential collaboration, one centered on the idea that the most mundane events have “a sense of magic,” says Copson. They were ultimately drawn to the film Last Days. Both of them were not much more than toddlers the day Cobain died, but as the rest of the ’90s unfolded, they grew up immersed in the pop culture of the moment, still dominated by rock and a Britpop movement led by Oasis and Blur, ultimately leading to the rise of the increasingly experimental Radiohead. “Of course I thought it looked really cool—I still think it’s cool,” says Copson. “There’s the idea of ‘cool’ being non-fazed, by saying, ‘No, I don’t subscribe to this.’ It’s something that’s undoubtedly been lost, or at least shifted into something else altogether.”

The first step to creating the opera was reaching out to Van Sant. “I sent him an email, sort of suggesting that we were thinking about it,” says Leith. “He just said, ‘Yeah, great idea, sounds good.’” Beyond that, the filmmaker encouraged Copson and Leith to take the material wherever it led, and didn’t impose any limitations or control over its final form. “He quite rightly said, ‘Just do what you want with it. That’s the best approach,’” recalls Copson. “At one stage we did ask him if there was a script for the piece, and he sent us back a 2005 Word document, which had two pages and some notes on it. That was very much the way that the film was produced.”

“I think [biopics are] a really gross genre because they ask for an audience to suspend their disbelief in some kind of idea of authenticity, which can never, ever exist.” — Matt Copson

Cobain was a hugely impactful public figure, a direct influence on a generation of artists and listeners, and on many more who discovered him after he was gone. His story is too pervasive to not attract the attention of artists working in multiple disciplines. Cobain’s story will fuel interpretation and reinterpretation indefinitely. In that way, Last Days is little different from stage director Robert Wilson tackling Albert Einstein with the help of composer Philip Glass on the acclaimed opera Einstein on the Beach. Likewise, in 2005 the minimalist composer John Adams and librettist Peter Sellars premiered the opera Doctor Atomic, a musical exploration of Robert Oppenheimer’s work on the first nuclear bomb.

Last Days is much closer to that lineage than the classic rock biopics Rocketman and Bohemian Rhapsody. “We love Robert Wilson,” says Copson, who came to the material neither as someone from the pop music world or traditional opera. “I hate biopics. I think they’re a really gross genre because they ask for an audience to suspend their disbelief in some kind of idea of authenticity, which can never, ever exist.”

Next up for Last Days is a film version of the opera, leapfrogging back to the material’s original medium. After the LA performance, Copson says of plans for a movie: “We’re about to enter pre-production on the film and it will be a completely cinematic envisioning of the opera for cinematic release.”

Rousselle expects to be onboard for all of it. “It’s very early stages right now,” she says of the movie version of their opera, but adds, “Anything related to this project would excite me. We had a proper collaboration, which is my favorite way of working. Everything about this project made sense to me.” FL