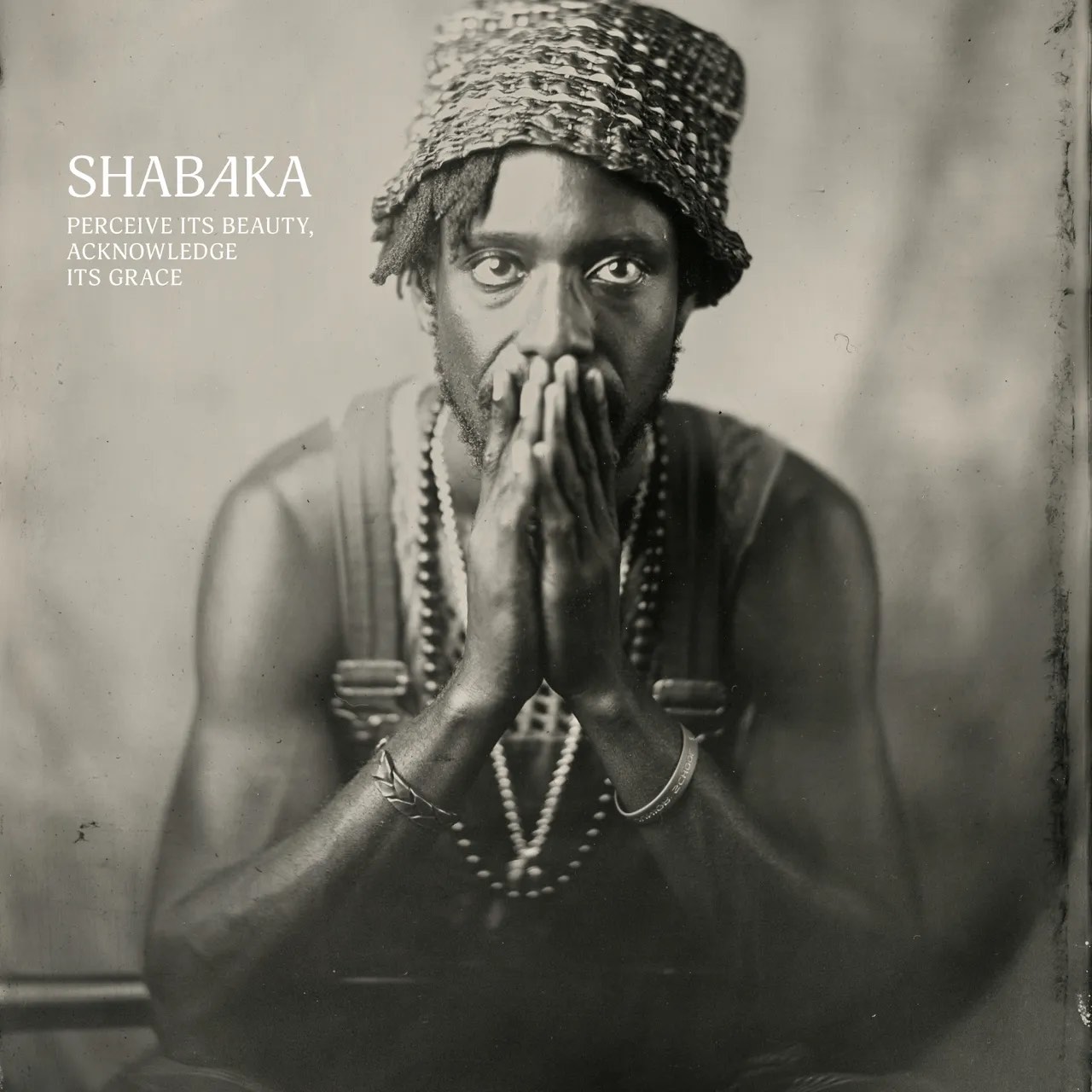

Shabaka

Perceive Its Beauty, Acknowledge Its Grace

IMPULSE!

A celebrated musician—widely lauded as a generational talent and a technical virtuoso—sets aside the instrument he’s most famous for. He says that he’s getting too old, too burned out; that he has nothing left to say. Instead he picks up a flute, he calls the LA new-age/jazz guru Carlo Niño, and cuts an album of soothing ambiance. Does this sound familiar?

No, this isn’t a story about André 3000, the iconic OutKast rapper who recently traded verbal dexterity for wandering woodwind solos. It’s a story about Shabaka Hutchings, the acclaimed saxophonist who’s one of the most heralded jazz prodigies of his generation. Leading influential groups including Sons of Kemet, The Comet Is Coming, and the Ancestors, Hutchings built his reputation on scorching solos, instrumental pyrotechnics, and music with a distinctly political charge. His playing has always felt like it’s born out of friction, which is precisely what makes his new solo album, Perceive Its Beauty, Acknowledge Its Grace, feel like such a left-turn. It’s not just that he’s cast aside his trusty sax; it’s that he’s shifted from kinetic energy into meditative tranquility. Is it possible for an album to be both calming and jarring at the same time?

It is difficult to avoid direct comparisons to last year’s New Blue Sun—not just because Shabaka and André share so much overlapping personnel, not even because André himself shows up in a supporting role with Shabaka. There’s a much deeper spiritual kinship between the two albums, both of which draw equally from the jazz and ambient traditions, and both of which sound like the kind of music you’d hear in an herbal tea shop or in the backdrop of a yoga video. The kinship exists not just in the music itself, but also in the metanarratives: Both albums are more moving when you hear them as efforts by their creators to cast off the demands of celebrity and expectation and to instead make music conducive to a slower pace and a more generous sense of self-care.

But there are also important distinctions. André is a relative amateur, and his flute album felt deliberately unformed, drifting, and exploratory. Shabaka is rigorously trained, and although he’s playing his secondary instrument here, the album still feels tightly constructed and carefully planned. Its 47 minutes never move beyond a languid pace but neither do they feel aimless, and the warmth of flute, harp, and piano are often joined by sung or spoken lyrics. The album’s mood is so unerringly zen that collaborators—of which there are many—tend to disappear into the vibe; luminaries like Jason Moran and Laraaji make unobtrusive appearances, with only “I’ll Do Whatever You Want” and its synthetic pulse from Floating Points registering as a significant sonic wrinkle.

It might also be said that the emphasis on self-care and mental health can border on being too instructive, too beholden to new-age cliché. A verse from the spoken-word poet Saul Williams on a track partly titled “Managing My Breath” is about exactly that. Framed by Shabaka’s personal history and by his stated intentions for the album—to say nothing of his command and control as a performer—these gestures toward personal healing and emotional regulation come across as sincere; and while this may not be as exciting as the music Shabaka made from a place of friction, it makes a decent case that rest can be beautiful and rewarding in and of itself.