The plight of those in prison—guilty and innocent—has always been at question when it comes to the most basic of human rights. How does the prison industrial complex care for its charges, work toward true rehabilitation, and tend to the needs of the incarcerated? The independent label FREER Records (formerly Die Jim Crow) has answered those questions, musically, since 2013 with the release of rap albums that speak volumes to racial injustice in the US prison system, along with newer albums such as its recent LP from Lifers Groove, whose membership represents “150 years of time spent in the American prison system.”

Yet back in 1973, Pennsylvania’s Graterford Prison was the home to Power of Attorney, a raw-knuckled funk ensemble who wound up getting signed to a major label (Polydor) due to a cosign from James Brown, had their sole studio album produced by Stan Vincent (known for R&B hits such as “Ooh Child”), got their instruments and equipment from Alice Cooper (Alice’s manager Shep Gordon befriended PA State Rep Jim Kelly), and won its greatest acclaim when vocalist Ron Aikens joined the band.

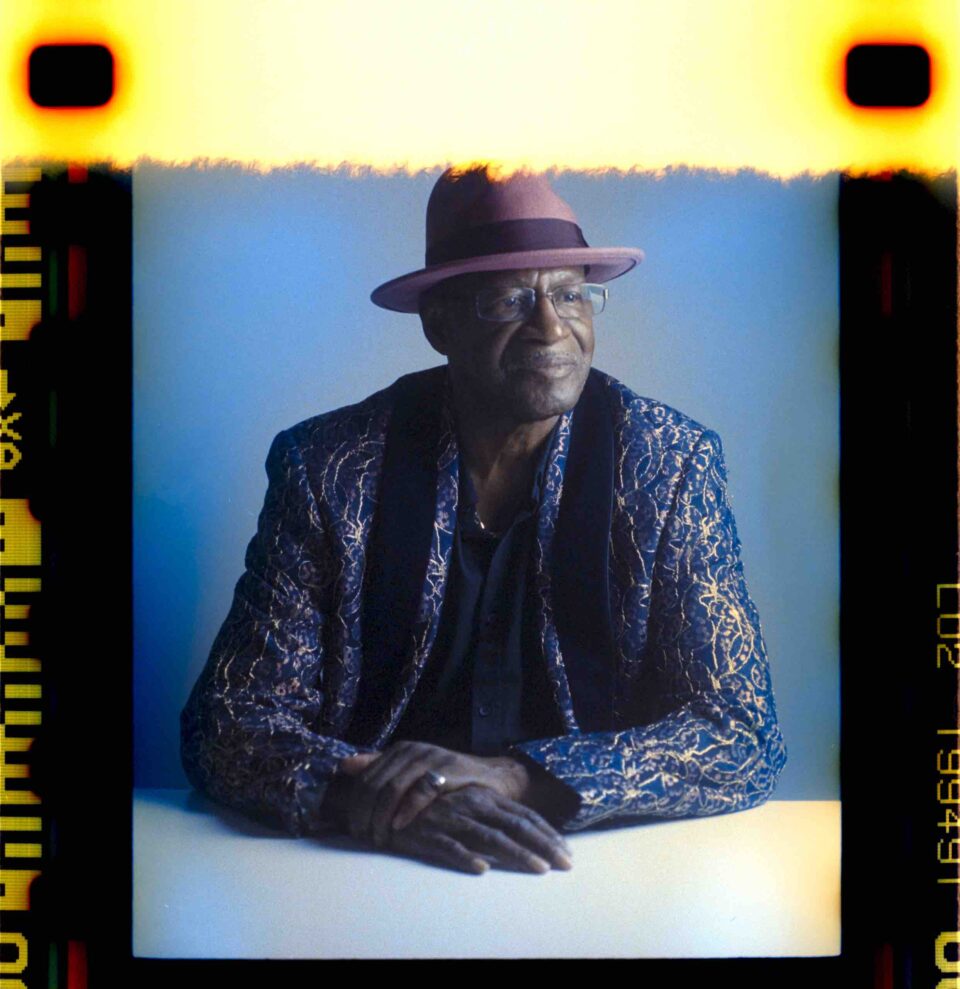

Aikens had to take his time finding his footing as an artist after his release from Graterford in 1976—48 years of false starts and lying business partners, if you’re counting. But now, with the help of one young label owner in Brewerytown Records’s Max Ochester, freshly written compositions by a handful of Philly Soul devotees, and old-school arrangements from Sigma Sound Studio veterans (think everything Gamble and Huff, along with Bowie’s Young Americans), Ron Aikens, in his mid-seventies, is truly free from the prison of his mind. “No one had ever done this before—recorded an album with prisoners, taking them out of their cells and bringing them to the best studios to release music on a major label,” says Aikens, proudly, of Power of Attorney. “We were the first.”

Though he’s a million miles removed from his past, he holds his time with Power of Attorney like a badge of honor, despite the fact that he’s still haunted by the crimes of his youth. “It was a family thing,” Aikens says of his relationship to music as he references his brother, a member of the corner-hanging doo-wop group The Guy-Tones, and his father who managed that vocal ensemble. “I always imagined that I could sing, and when they gave me a shot, they didn’t yell ‘next.’ They even asked me to sing another. And another. And I got caught up in wanting to be a singer for real.” Headlining spots at talent shows in and around South Philadelphia, blocks from where Chubby Checker got discovered (“He didn’t even want to be a singer…my brother was the one everybody thought stood the best chance at success”), Aikens furiously sought out opportunities to sing in front of a band.

In 1969, Aikens got that chance by joining United Image, a Philly soul group signed to Memphis’ Stax Records. Though there was a lot of gang activity in the South Philly of his youth (“Every numbered street had a gang named for it”), Aikens stayed out of trouble—until he didn’t. “I navigated my life so as to never be in a gang. I wasn’t a cool guy. I was quiet and stayed to myself.” Aikens wasn’t used to the attention of young women and the sartorial splendor of nice clothing that came with burgeoning stardom. “I just went outside of myself,” he says, tearily. During this interview, you can hear in his cracking voice how horrible he still feels that he hurt another human being. “It’s shameful. It was tragic. It went downhill from there.”

Aikens doesn’t shy from his wrongdoing or his arrest at age 25 on statutory rape charges. Ochester and Aikens both discuss how the vocalist is actively seeking therapy now—something that wasn’t available to those who were incarcerated in the past—to further answer the questions of his indiscretions. “I’d like to get a handle on how that ever came to be,” he says. “I understand that it was not good and can’t ever be forgotten, even if I am a different man.”

“No one had ever done this before—recorded an album with prisoners, taking them out of their cells and bringing them to the best studios to release music on a major label. We were the first.”

Aikens broke out in tears when he first heard now-members of his Hip Tones collective Dave Cope and Fred Berman’s “Criminal.” Written as a picturesque narrative of a man who can’t escape the errors of his past, Aikens stated that while the song isn’t biographical, it’s part of his need to sing songs that are healing. “I haven’t found the lyrics inside of myself to write those songs, so when I hear something so descriptive, it reaches deep inside me.” Ochester observes how Aikens “sings better” when gifted with tracks that speak to his hard life’s experiences. “Dave and Fred wrote about someone wrongly accused of a crime, and convicted. That wasn’t Ron’s story and didn’t connect with it, so we wrote it in accordance with someone who did do a crime, spent time in prison for it, and has re-written his life’s story after his time in jail.”

Seeing the glass as half full rather than half empty, Aikens took every opportunity to sing his soulful ass off while spending a year as part of the Pennsylvania’s county jail system before heading to Graterford. In fact, it was when members of United Image surprised Aikens by showing up and backing him during a jail auditorium talent show—with several musicians from Power of Attorney and Graterford’s activities head Ted Wing scouting Aikens from the audience—that the vocalist made his might known. “If I was ice cream, I would’ve melted,” says Aikens about his first clear opportunity to shine in front of the prison elite.

Aikens wanted in on Power of Attorney in the worst way. Not only were these musicians hard-driving and devastatingly funky, they played a multitude of prisoner-related live shows, and made a name for themselves opening for Stevie Wonder before Aikens’ tenure. “What made Power of Attorney interesting to me was that though some of these guys were lifers, they were trying to give something back to their community—performing in prisons, showing fellow prisoners that there was more to life, more to us, than just what we were: in jail,” says Aikens. More easily said than done, it was initially only Wing who wanted Aikens in the prison band-of-renown. “Ted was like Max in that he was, sometimes, the only guy who could see something even when no one else did,” laughs the vocalist. “Ted knew that I was a tight fit for Power of Attorney, and he knew like I knew they needed a frontman. They needed someone with a little more fire.”

The only member of the band who was initially enthusiastic about Aikens was bassist and vocalist Charles “Cha-Cha” McDowell, who solidly bonded with the singer—not only in prison, but for the rest of their lives on the outside. “Charles liked me, but knew [keyboardist/bandleader] William Smith wasn’t having it. Schmitty was like Otis of the Temptations: that mainstay wielding any power over the group to keep the band in line and not mess up.”

There were a few mess-ups with PoA, but not the way one might imagine—such as the band members who were scheduled for full release from prison in mere days (such as flutist Dwight Williams with three days left on his sentence), only to plan elaborate escapes that found them under arrest and happily back at Graterford (“On the outside, you’re nobody,” Cha-Cha was known to say, “but in prison, you are the Power of Attorney”). Aikens states that he had his own problems leaving Graterford when his time in jail was up. “In here, I’m on Polydor Records. I’m on television shows. I’m touring everywhere. When I get released, how am I going to recreate that on the outside? I was happy and excited to be home, but I was afraid. I’d have to stand on my own two feet. And I didn’t really believe in me.”

“In here, I’m on Polydor Records. I’m on television shows. I’m touring everywhere. When I get released, how am I going to recreate that on the outside?”

Ron Aikens’ entrée into Power of Attorney only came when Stan Vincent came to Graterford to hear what the band had. Filling in for PoA’s drummer when the stickman was released from Graterford during Vincent’s audition session at the prison was Aikens. When the producer listened to the band, and asked for another vocalist, Aikens volunteered and bowled Vincent over with his power and his prowess on a rendition of Gladys Knight’s “Neither One of Us” in her key of D. “I knew everything about every note,” recalls Aikens enthusiastically. “I was like a vulture ready to pounce.” Having impressed Vincent with his sonorous tones, the burgeoning production legend came with an ultimatum: “Bring this guy Aikens in, and I’ll record an album.”

After Aikens assured PoA’s skeptical braintrust that he wouldn’t be “an ego-tripper,” the new vocalist officially became a part of the prison ensemble. And rather than use Philadelphia’s Sigma Sound Studio where PoA recorded several sturdy demos, Vincent “insisted on doing it big” and brought them to New York City’s Hit Factory for the recording of their Polydor album, From the Inside… “Vincent did everything to get us from Graterford to New York in several Greyhound buses—he had to get permission from three governors to cross state lines, had motorcycle-led motorcades going across each turnpike. The media guys were there when we got off the bus, and I kissed the ground. It was just amazing. In fact, Cher was recording in the same studio we were in, and asked if we could switch rooms as that was her favorite. We did, happily, and she provided all of us with tons of food and drink.”

The lone Power of Attorney album, From the Inside… was released in 1974 to great fanfare, with TV appearances for the band and features printed in local newspapers across the country. Aikens was released in 1976, and thought that a second PoA album would happen despite his release. That never happened. Graterford’s first Black prison superintendent, Robert Johnson, the man who green-lit the program, wasn’t around to let Aikens into the prison. “They shut the door.”

It’s not as if Ron Aikens gave up on music after he got out of prison in 1976. Far from it. “The fire was still burning in me,” says the singer. Along with linking up with Vincent in New York for several of the producer’s tracks with a gaggle of vocalists backing him (one of which happened to be the legend-in-waiting Patti Austin) and singing one-offs under the disco-era monicker Doc, Aikens & Shields, Ron wound up getting scammed on his participation in the creation of the once-famous Pop Art label—a tale so richly detailed in its sly, arch-criminal fiduciary weirdness, the writers of Succession would be green with envy. “Sometimes all someone has is their hustle and bad intentions,” says Aikens, pragmatically, of being told he had a piece of a label when indeed he held nothing but trouble and one record titled Galaxxy featuring Ron Aikens. “Some people in the music business are not kind.”

“Sometimes all someone has is their hustle and bad intentions. Some people in the music business are not kind.”

Eventually, while working as a janitor at Philadelphia’s City Hall for 30 years and busking under the name “Ron Jaimz,” Aikens met someone in the business who was not only kind, but who saw a way for the vocalist to enter the indie music business that borrowed from his past and benefitted from the public’s thirst for vintage R&B with a twist. “I had just gotten the rights to the tapes of pre-Aikens’ Power of Attorney from Drexel University [who houses nearly all of Sigma Sound’s masters] and was getting ready to release ‘Changing Man’ when I saw Ron singing outside,” says Ochester. “Those sessions weren’t done with Ron, so he didn’t know them immediately. But once he caught on, he was amazed. We built a friendship. Then I saw a more recent video of him doing ‘A Change Is Gonna Come.’ Suddenly I realized that rather than just release old ’70s music, I should get Ron to do new original music we could create from the bottom up, build a group around him, and get his amazing voice and immense talent out there.”

Knowing, too, that there was a lane for the old-school R&B sound with barn-storming singers such as Sharon Jones, Lee Fields, and Charles Bradley, Ochester and Aikens worked quickly, found soulful “white kid” musicians to write for and play to, and even wound up bringing in brand-name session cats (including The War on Drugs’ Charlie Hall) to create a full album set to be released imminently whose guts and gall, whose blood, sweat, and tears, capture the singer at his finest. Like fine wine, Aikens’ vintage only got more robust with age.

“When Max, Dave [Cope], and Fred [Berman] first came to me with ‘People’ [his first new Brewerytown single, released last September] and ‘Criminal,’ I just didn’t see it,” admits Aikens with a laugh. “But there’s a certain look that Max has in his eyes. I could see he believed in me. Stan Vincent had that look. These are people who fall in love with your gift. So whatever Max, Fred, and Jim wanted to do—whatever I had to do to get what these guys wanted from me—I would be there for it. And I love every note and word I’m singing. Max has an ear, even though he said that he doesn’t know what he’s doing. Hey, I don’t know what I’m doing, either. If it all went off the cliff, I’m going down with them. If It’s all going up, I’m sailing upwards. Let’s do this shit.” FL