John Lennon

Mind Games: The Ultimate Collection

CAPITOL

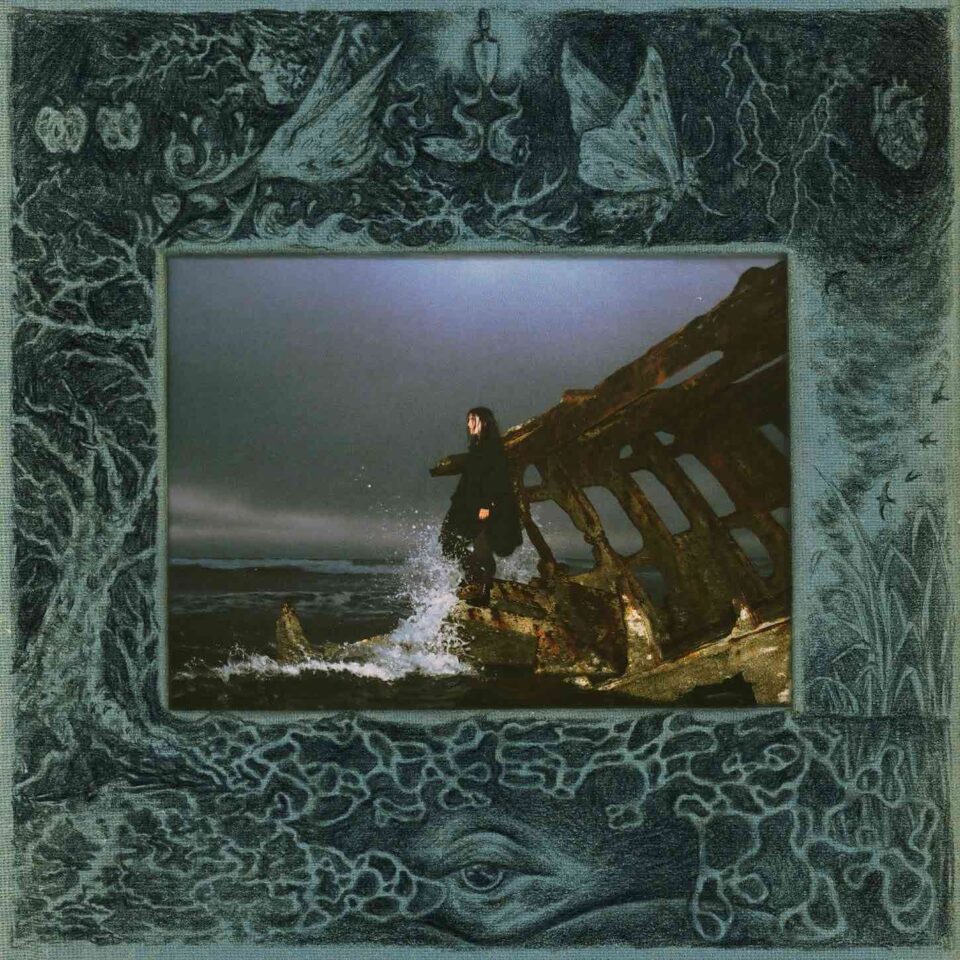

Listeners (and, more so, consumers) accustomed to a world of refreshed and intimate Atmos sounds and heartily expanded albums in elaborate packaging know how the catalog of John Lennon—Beatle, husband to Yoko, solo artist—has become architectural in its new renderings: art pieces to behold beyond the necessity of their music and lyrics. Which comes to a head on this month’s stylized repackaging of Lennon’s self-produced and most-maligned recording, 1973’s Mind Games. Sold in one fabulously gluttonous iteration as a 30-pound Super Deluxe Edition cube, everything held within—including a Perspex reproduction of Yoko’s famed Danger Box art piece, interlocking puzzle blocks, and a wealth of Easter eggs—is designed to physically portray just what was going on inside the Lennon/Ono brain trust circa summer 1973 in New York City.

Plagued by a disintegrating marriage and an FBI investigation that threatened his stay in the US due to the couple’s political activism, Lennon emerged from a long-term writer’s block with often contradictory melodies and lyrics, diverse in quality and density of message. Were the title track’s refrain—“Love is the answer”—and the adoration he welcomed on “Out the Blue” truly heartfelt sentiments if his relationship with Yoko was so quickly falling apart? Was Lennon really looking for forgiveness, per the messaging on “Aisumasen (I’m Sorry)”? Were rockabilly and boogie blues the music that could best convey the stories behind “Tight A$” and “Meat City” in 1973? And even though Phil Spector had often added too much fluff to his previous solo outings, were Lennon’s self-production techniques so much better?

All of those questions were certainly among the criticisms Lennon heard after Mind Games’s release. Yet the superior mix and mastering of 2024’s re-release—overseen in hands-on fashion by Sean Ono Lennon with era-appropriate rarities and outtakes galore—allows fan and novice alike to separate the wheat from the chaff and clarify this once-blurry set of Games with new luster and warmth. With Lennon’s original solo output marred by a muddy and quickly dated production style further weighed down by too much ornamentation and zero clarity, this new Mind Games affair offers two discs that truly (and, yes, literally) shine and stun among its six CDs and two Blu-rays: a set of “Elemental” mixes with heightened but stripped-back sound that push Lennon’s emotional vocal pleas to the front of its tracks (sans a drummer’s busy bottom end).

There’s also a set of raw, early studio mixes with barely an effect (or vocal) to be heard. An all-instrumental album might seem a counterintuitive tactic if you’re looking to heighten Lennon’s status within the controversies of Mind Games, yet hearing how the legendary artist-activist perceived his ensembles actually gives fans an idea of how he heard his arrangements apart from his brand of storytelling. There’s also an “Evolutionary Documentary,” an audio-verite track-by-track study of how Lennon & Co. got from the demo stage to the master recording with their rehearsals, outtakes, multitrack exploration, and studio conversations intact.

Whether we’re talking about the sculptural Super Deluxe Edition (which is already sold out—check eBay) or the more-affordable, still-stuffed Ultimate Collection, what any configuration of Mind Games can’t do is improve the quality of Lennon’s songcraft circa 1973—with but a few exceptions, the album was not his best material melodically nor lyrically. What Mind Games does do, however, is find Lennon swimming through the waters of being alone (he pretty much went from his brotherly fellowship fishbowl of Beatles fame to the married partnership of Yoko) for the first time. You can hear a tentative Lennon poring over the sentiments of earthly and unearthly devotion and protest rhetoric that filled his previous work (to say nothing of the music of his youth) and coming up with a roughly romanticized stop gap between the trippy mess of 1972’s Some Time in New York City and 1974’s wildly confident triumph Walls and Bridges. With that, the journey of Mind Games is worth its weight.