Thursday, January 16, 2025: a man I considered eternal died. David Lynch—filmmaker, artist, musician, sound designer, cartoonist, chain-smoker, YouTuber, human—pervaded and propelled my growth as not just an insatiable fiend for popular culture, but my maturation as a human. If that sounds hyperbolic, I assure you it’s not. His influence on me—and on all who have experienced him, all who are willing to give in to the indelible beauty which is unique to him—is that profound, that inimitable.

What defines Lynch’s work is the insoluble sagaciousness, the depth and earnestness and daring of his knowledge expressed abstractly and earnestly. Lynch’s is an almost sacred understanding of the unknowable that suffuses each frame of his moving images. He made insightfully cryptic art, on screens big and small, eliciting a feeling both seen and unseen, audible and unheard, palpably fluttering like wings in a heart in love. Yes, there’s murder and yes, there’s suffering; but always, there’s love. He marries dichotomies in pursuit of honesty. His works are mysterious, but not mysteries, as a mystery has a solution; no, Lynch’s vision howls with the ache of human fallacy, as well as empathy and beauty.

While it may initially irritate you if you need to solve the riddles of surreal art, with Lynch’s films you soon learn to luxuriate in the sensation of not knowing, to feel rejuvenated by the fact that you can analyze and evaluate and have your conclusions constantly changing as you change. In such, his works will exist into infinity. He posits, ruminates on, and never feigns answers to our everlasting condition as life on a planet we can never fully know, but for which we must wish the best. “I almost love people,” Lynch told us in our 2022 cover story, “not quite, but almost love people. I just think I almost love the whole show, the whole world.”

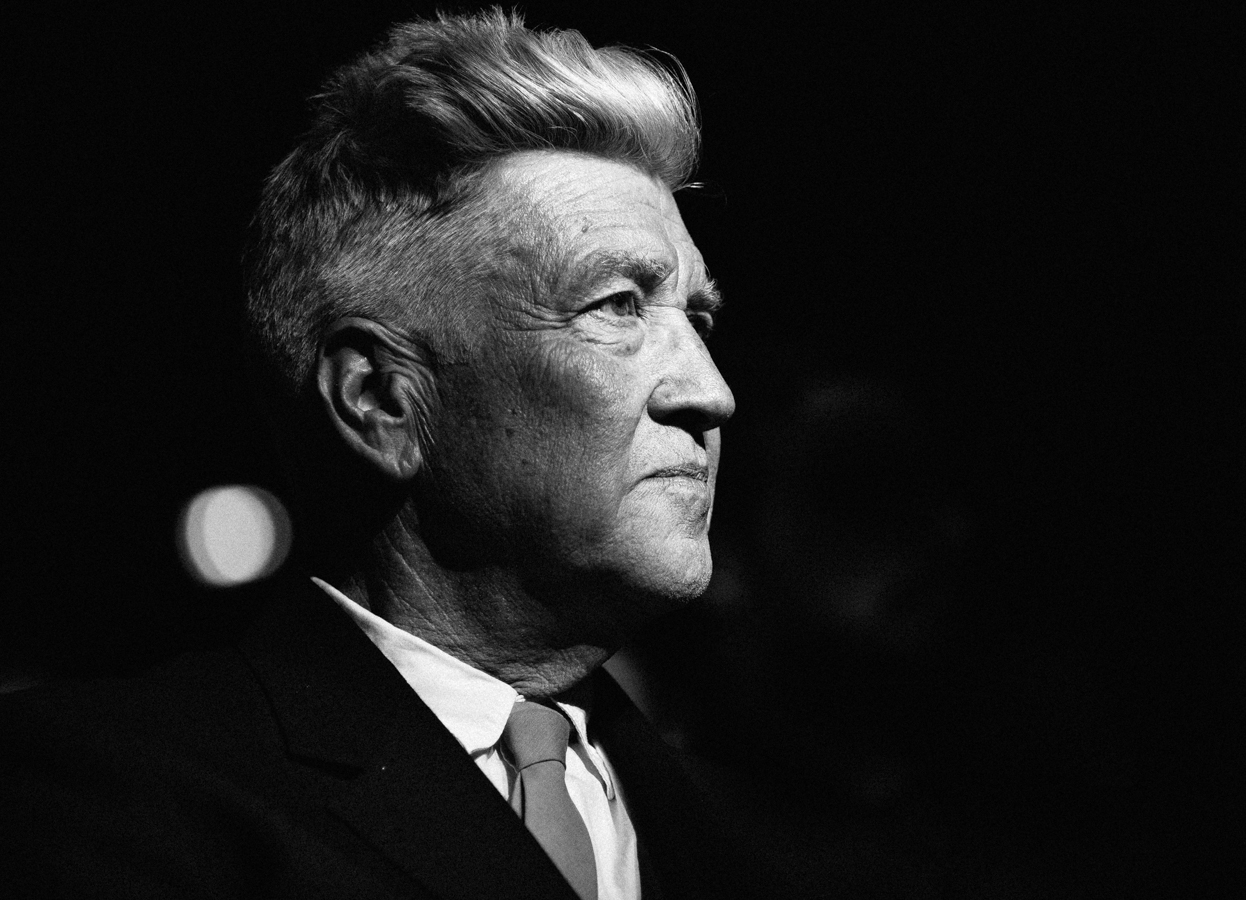

David Lynch at home, Hollywood, Calif.

Lynch’s early works include The Grandmother, a nightmare of juvenile fear in the face of geriatric menace, and the seminal Eraserhead, an assiduously crafted, long-in-production personal work into which its creator imbued extreme effort and a lifetime of honesty. Consider that agonizingly slow elevator, the mutated baby, the zombie chickens spewing black blood, the fear of fatherhood lingering throughout like foul air as the starkly lyrical and lurid black-and-white images flicker threateningly. It’s considered one of the first midnight movies, events held at the witching hour where acolytes would accrue in a big, dark room smelling of popcorn and become themselves part of the viewing experience. Later work—including Inland Empire (a film truly untethered to reality, yet so deft at showing us a different, deeper, more real reality) and the inscrutable, unscrupulous cartoon DumbLand, an incredibly abrasive achievement in nonsense—return wave-like to these embryonic oddities.

I did my senior thesis on Blue Velvet, one of David Foster Wallace’s favorite films and, at least initially, one of Roger Ebert’s least; my professor considered it an evil film and gave me a C-. The iniquities depicted burrow bug-like into the more vulnerable parts of the viewer, making your heart squirm. Of his first viewing of Blue Velvet, David Thomson wrote: “The occasion stood as the last moment of transcendence I had felt at the movies—until The Piano. What I mean by that is a kind of passionate involvement with both the story and the making of a film, so that I was simultaneously moved by the enactment on screen and by discovering that a new director had made the medium alive and dangerous again. I was the more captivated in that I had not much liked David Lynch’s earlier work.”

Lynch, the son of a surprisingly normal man who worked as a research scientist with the US Department of Agriculture, made some more “mainstream” films, too, more normal, maybe: The Elephant Man and The Straight Story, both still distinctly Lynchian. These lyrical stories of man’s triumph over fate are the ultimate hope for all of us, which is present, if barely perceptively at times, in all of his features. But whereas in Lost Highway the hope is darkly redolent of, say, Kiss Me Deadly’s final moments—hope meant to be wounded—Elephant Man and Straight Story end with lovely optimism, not forced, but utterly truthful and confident with the never-impossible chance for anyone to find happiness. Wild at Heart, too, is romantic and hopeful, trembling with libidinous and loving passion. Lynch knows that we’re all human, and we all matter.

But with Lynch, even the mainstream is weird. His one and only blockbuster, Dune, eschews all discernible traits of the big-budget studio monstrosity; instead, Lynch conjures a different kind of monster, an unrepentantly and unadulterated vision wholly his own with which we wildly ride through hallucinatory beige sprawls of alien desert rife with gigantic worms and Sting stripped to his dystopian undies.

And then there’s Twin Peaks, a series whose importance is hard to aptly articulate—to American culture and to myself. It premiered in April of 1990, not even three months after I was born. Dale Cooper enters the town of Twin Peaks on February 24, my mom’s birthday. It’s been with me my whole life. Before I ever saw the show, I knew its place in American culture as essential, both the best thing ever and too weird for its own good, depending on who you asked (note Homer Simpson’s comments on the show’s brilliance). “Who killed Laura Palmer?” ads festooning newspaper pages and commercials on TV. “Who killed Laura Palmer?” the country asked. It was heralded as a medium-changing work from the pilot, which got an A+ from Entertainment Weekly, as mainstream as cultural criticism gets. But, impatient for closure, many viewers abandoned the show before they found out the answer to this question in the second season, a testament to television’s purpose in the early ’90s: to entertain easily, not to challenge. Today, everyone knows that the answer is not the point.

I put off watching the finale for years, wanting something to look forward to for the worst parts of life I knew were coming, and wanting to prolong the end of a life-changing experience. I had unreasonable expectations; Lynch would meet them all. When I went to Syracuse for my Masters, we’d spend a week on Twin Peaks, ending with my professor showing us the finale on the auditorium’s theater-sized screen. He understood the show’s perdurable power. So I finally finished the show many years and several almost-complete viewings later. I emerged from that class a different person. Laura Palmer’s screams, soul-shattering, echo forever in my ears.

The short-lived On the Air, uproarious in the sense that you laugh more internally than out loud, and harder than at conventional sitcoms, pushed the boundaries of television standards even further. It deserves a bigger fan base. And nearly a decade later, Lynch obliterated the rules of narrative cinema with failed-TV-show-turned-movie Mulholland Drive, maybe now his most popular film. It’s the story of a pretty young blond (Naomi Watts), genuinely innocent and dreamy in the eyes which glint like Hollywood lights, who moves to LA to become a star. Hollywood has never been so sweet, and so scary. The DVD comes with a “key,” a list of points to keep in mind which will ostensibly solve the mysteries of the film; yet any fan of Lynch’s knows that this is itself a part of the film, a postmodern play on public reaction to his work.

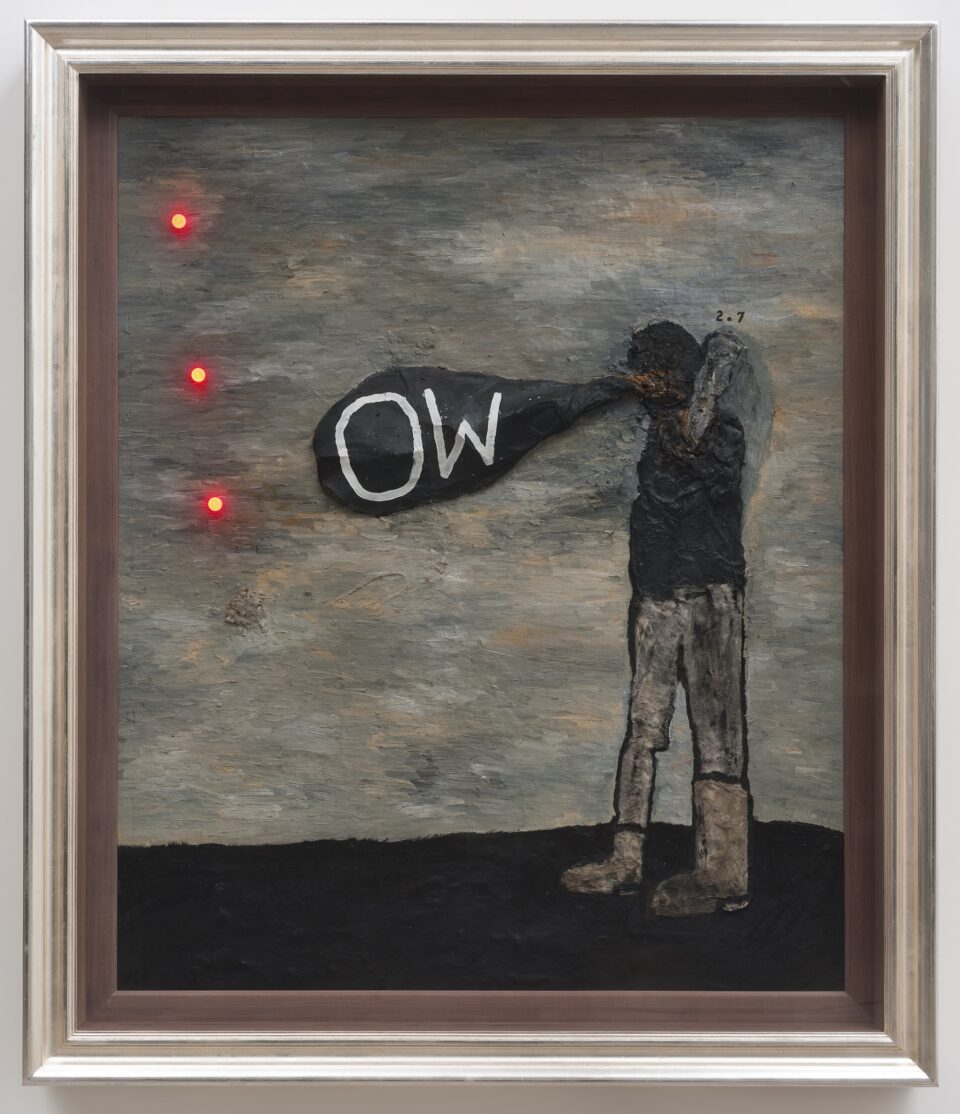

Woman with Small Dead Bird, 2018

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me was greeted with vitriol in 1992; it’s now revered, thankfully, yet still not quite enough, which it never will be, inherently, as it’s removed from its epochal context. Millennials are unable to appreciate its belated, intense re-evaluation, because we weren’t among those initially stung or those who found themselves feeling alone in their ardor. Its ongoing life is, itself, a part of Lynch’s lifelong fascination with the ineluctability of aging. The boldness of it is at once lost in time, and still there. It opens with Angelo Badalamenti’s lovesick swoon of horns over a sea of blue writhing static—a television screen, we see as the camera recedes, a small bulbous thing found ubiquitously in living rooms around the country in which families gathered to watch Twin Peaks, people desperate for answers which Lynch teases but delays for so long, destroying us when he does finally answer those questions which everyone pondered with such frightened anticipation. Then the screen erupts. This is not the show, Lynch is saying; you have no idea how much I am about to hurt you.

Within the first two and a half minutes of Fire Walk with Me, David Lynch has, as they say, killed his darling. The film remains a unique piece of Lynch’s singular body of work: it begins with a tease, like a kick in the teeth of dumbly smiling fans—not mean or anything, but to make sure that you’re paying attention, to make sure you know that Lynch will not coddle us. There are no birds, no saws chewing through logs or machines sharpening the blades of other machines, no voluptuous collapsing waterfalls or bucolic woodlands. The first few shots include a profile of Lynch himself before a painting of trees and an FBI agent arresting a school bus of children. Very Lynch. The subsequent two hours are a vexatious traipse into the chthonic agonies of Laura Palmer’s final days. It’s the scariest, most tragic movie I’ve seen, and it is beautiful.

It’s also impossible to capture the quivering excitement of waiting for 2017’s Twin Peaks: The Return in the hours leading to its premiere—or, rather, the moment when it was unleashed upon an unprepared world, which it would both depict astutely and render even stranger than just the previous day. An 18-hour exegesis on humanity’s inability to ever understand its own purpose and possibilities, The Return is neither show nor film, but an unprecedented work of visual and narrative art—a seismic event that sends reverberations still felt eight years later, none of which have produced a film or show as profound (the iconic French film magazine Cahiers du Cinema considered it the best film of the whole decade!). I won’t waste time failing to do it justice. But one moment which keeps eddying around my head right now is when Harry Dean Stantion watches a soul galvanized as a golden glowing orb ascending to—where? Heaven? Wherever it is, David Lynch is now there. And here. Here, forever.

David Lynch—as a man of flesh (and with coffee in his veins), as an artist with an undying soul whose vision is personal and strange but never solipsistic—always has and always will defy understanding, beguiling us into deeper and darker and more heavenly depths as time unspools like frames of a film, and as life trundles on, ferrying you along with it. You carry Lynch with you until you die—maybe after, too. FL