Joe Strummer may have been alluding to The Clash when he wrote the punk anthem “Last Gang in Town,” but for my money, it’s James Fearnley, Spider Stacy, and Jem Finer—the remaining co-founders of The Pogues with the late, great Shane MacGowan—who are, indeed, that last gang standing, albeit one with an Irish politic-poetic Brendan Behan/Dan Breen edge. Besides, even Strummer became a Pogue for a minute; to not be a Pogue when called upon would be folly. Ask the trio of men who still stand proudly as Pogues, currently celebrating their most rousing of times and poignant of memories.

In celebration of the 40th anniversary of 1985’s Elvis Costello–produced Rum Sodomy & the Lash—a multi-volume, re-release with all of the (tin) whistles and bells—The Pogues have been on tour with guests and friends joining with the forever family-bonded likes of Fearnley, Stacy, Finer, and the rest of their last gang. Now finished with their North American shows after a finale at Chicago’s Riot Fest, Fearnley reminds us of the beauty of The Pogues.

What can you divulge about the joys and pressures of keeping the ensemble’s name, vibe, and sonic signatures alive while holding onto your own individuality?

We’re close, Jem, Spider, and me—the way that the atoms in a molecule of methane are close, maybe, with covalent bonds and so on. The lattice that kept us together in the larger molecule that went before was a strong one. This molecule is a stable one by virtue of that, I suppose. I guess on stage it might have looked like we dissolve into the other musicians we play with, as many as 14 in total on the tour we just did—I counted 33 or 34 musicians when we played in Dublin last Christmas—and there’s Jem over stage left coming across as far-flung, perhaps.

I can’t stand still. We come out on the stage at the end, the three of us, to bow our gratitude to the audience for sticking with us, for suspending their judgement of us not being all the original six members. That said, people in the band came and went. The number of us went up. And keeping the ensemble’s name was tricky. There’s something just wrong about calling ourselves The Pogues. “What’s Left of The Pogues” or “Some Pogues” doesn’t sound right, as much as “The Pogues” doesn’t sound right when there’s only three of us. I guess we could’ve given the ensemble another name altogether. “The Pogues and Friends” and “The Pogues and Guests” were suggested, but we couldn’t make either of those work.

“Keeping the ensemble’s name was tricky. There’s something just wrong about calling ourselves The Pogues. ‘What’s Left of The Pogues’ or ‘Some Pogues’ doesn’t sound right.”

And the vibe, the spirit of the band, with the three of you as still-standing Pogues is preeminent.

The vibe has been a constant, I think, pretty much from day one. There always seemed to be a readiness about us from the very beginning—a readiness that might’ve come across sometimes as begrudging or resistant. There was always something to begrudge and to resist, but I think our readiness always came along to enable us to transcend what we might have begrudged or resisted. For instance—in my case, and maybe others in the band—the resistance of a completely unfamiliar instrument like the accordion, its resistance to being learned straight away. I didn’t begrudge learning it, I have to say. But it put up a bit of a fight. Together, at the beginning, we all learned to overcome the resistance our assigned instruments put up to our attempts to learn how to play them. We’re getting there.

And I guess that’s what you might call our “sonic signature,” too. I remember Spider contorting himself in frustration at one of our rehearsals. “What are we doing?” he shouted. “We’re knocking on the door of silence and awaiting an answer,” I said. Our sonic signature is the instruments that Jem, Spider, and I play: the banjo (though you’ll have seen [Jem] on the hurdy-gurdy on many songs—he’s committed to testing everything; that’s one of his jobs), the whistle, and the accordion.

Can you say something about what The Pogues are, spiritually or sonically, now that they weren’t when you recorded Rum Sodomy & the Lash? It’s all, quite frankly, uniquely “The Pogues.”

Honestly, it’s the songs that provide a through line, if not the thickest vein running through what constitutes our aura. If what we do is “quite frankly uniquely” The Pogues, it’s because of what Shane was in intimate connection with both the fund of music he grew up with and the experience he had in life. That’s pretty much why The Pogues sound like they do.

There was also something of a responsibility in representing Ireland, despite most of you being English—raw politicism that’s beginning to rear its head again in ensembles such as Kneecap. What do you have to say about the difference in generational sociopolitical lyricizing and representation?

I’m not sure I consider myself qualified to say much about that. I never felt much responsibility in representing Ireland. I never felt any such responsibility. I mean, how could I? I’m as English as anyone comes. When we recorded “Birmingham Six,” my dad’s lower lip jutted and his brows descended. “Remember,” he said, “you’re just an entertainer.”

I stood by Shane in pretty much everything he wrote. Well, there were a couple of infelicitous lyrics here and there that I wish I could have distanced myself from. More than anything, I remember coming across a kid in Northern Ireland in a bar who said to me, “How does Shane know about me?” History, humanity moving through time to something better—if they can—is a matter of people’s stories. Shane was devoted to them.

“More than anything, I remember coming across a kid in Northern Ireland in a bar who said to me, ‘How does Shane know about me?’”

During this tour, when you’ve brought out vocalists to the stage, what’s been your criteria for their one-time membership in the honored Pogues? And what is your warning to each about what will occur on stage?

My criterion is that Spider’s judgement of character is sine qua non. And their membership is in perpetuity. Warning’s not been necessary.

Who named the album’s title after a Winston Churchill quote, and why?

[Pogues then-drummer] Andrew Ranken was a fount of nautical lore. The album could quite easily have been titled “The Dance of the Flaming Arseholes.” Don’t ask.

Am I correct that Elvis Costello was brought in to do “A Pair of Brown Eyes” and “Sally MacLennane” first?

I can’t remember, to be honest. I always thought that Elvis was in from the beginning, for everything. Or maybe those two songs were intended to be singles, or a single and a B-side. I do recall Elvis going on about the talents of a friend of his—I can’t remember his name—who was good at “Radio 1 mixes,” to whom he sent a rough mix of “Sally MacLennane.” To my ears, “Sally MacLennane” sounds different, altogether more self-conscious, somehow. “A Pair of Brown Eyes” is sublime to me, and it was from the moment we started rehearsing it in the back bedroom at our friend’s flat in Whidbourne buildings in King’s Cross. Elvis just kind of super-sublimed it, if that can be a word. The roll on the snare kicking off the tambourine at the beginning of each chorus and in the hook is just genius.

What do you remember about the McGowan of Rum, the guy who wrote its entire first side? And what image of the band and Shane do you get when thinking of “Rainy Night in Soho?”

I described the day Shane came in to rehearse “Rainy Night in Soho” in my memoir [Here Comes Everybody: The Story of The Pogues]. He was wearing a dove-grey suit and latticed shoes. He might even have had a flower on his lapel. He was unutterably proud of the song, I could tell, the way he was stern with me about how the hook in the song should be played on the piano.

The first time I practiced with Jem and Shane in Shane’s room on Cromer Street, five whole days after Jem brought the accordion Shane wanted me to learn to my flat, we played “The Old Main Drag.” So, in a sense, that first side of the LP isn’t so much a snapshot of a period of time, it’s a landscape that places Shane against a backdrop of the whole of Europe, seems to me.

The new Rhino label remaster is packed with rarities. Was there anything you were particularly surprised to hear now, maybe that you forgot existed?

I’m elated to hear “A Pistol for Paddy Garcia” on the remaster. Not often one gets to whistle on a record—or live, for that matter.

Can we expect the three of you to come out in toto when the next remaster gets released?

You mean the 40th anniversary of If I Should Fall From Grace with God? I hope we’ll all come out in toto, as you put it. Can’t see why not. For Waiting for Herb, though, they might want to leave me in the ground.

Every time I’ve seen you play, there’s this immensity of warm feelings and genuine emotion when it comes to people in love with Shane’s memory and their adoration of you three as the last men standing. What say you about The Pogues’ hold over American audiences and that deep and abiding love?

The emotion, the love for Shane when we play, I’d say is universal—well, the countries, cities, fields we play. The adoration of the last men standing is our audiences’ projection of their love for all of us. I’d like to say we’re just the bedsheet on which our audiences screen their emotions for us all—and for themselves, too. FL

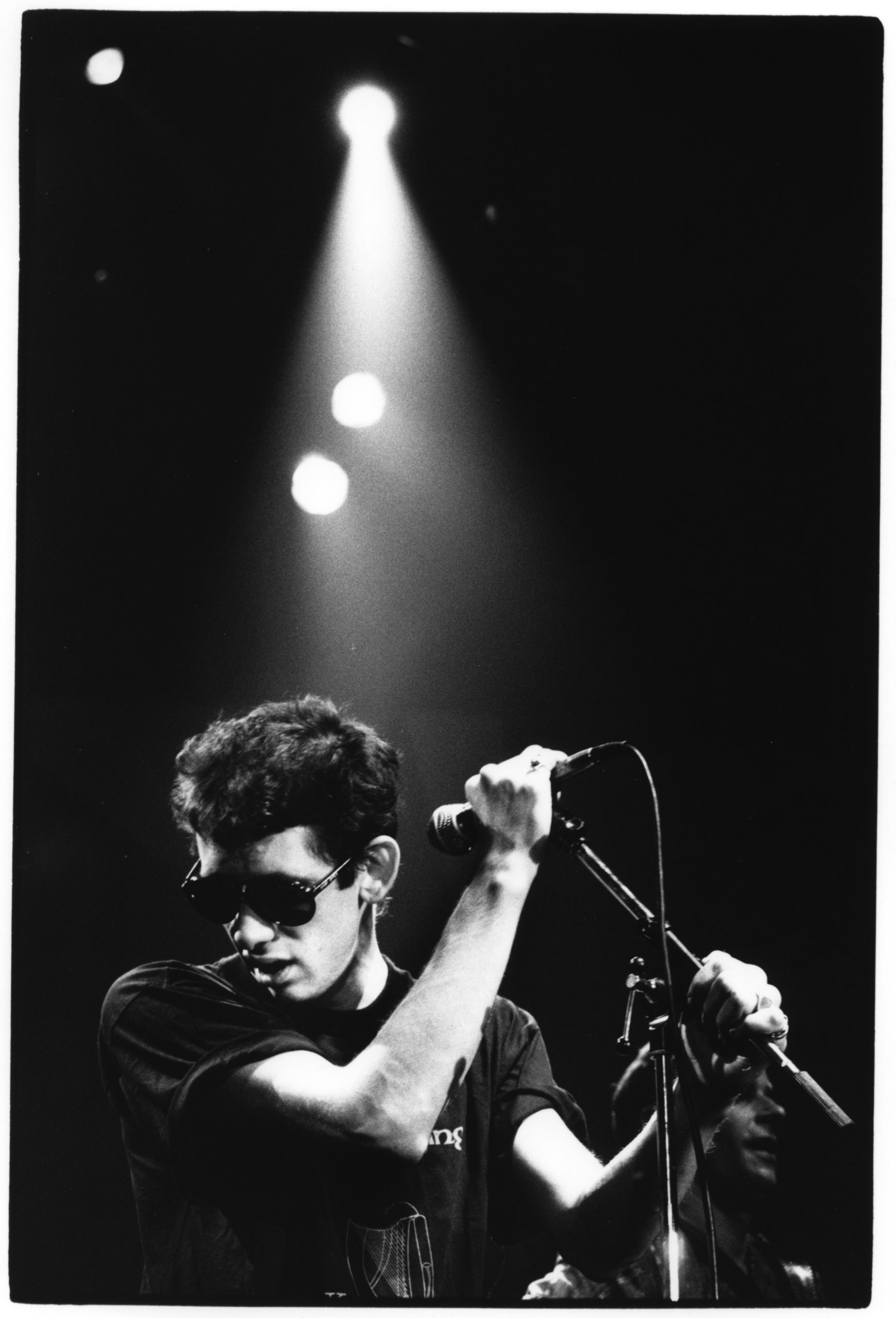

Shane MacGowan / photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures