Sturgill Simpson

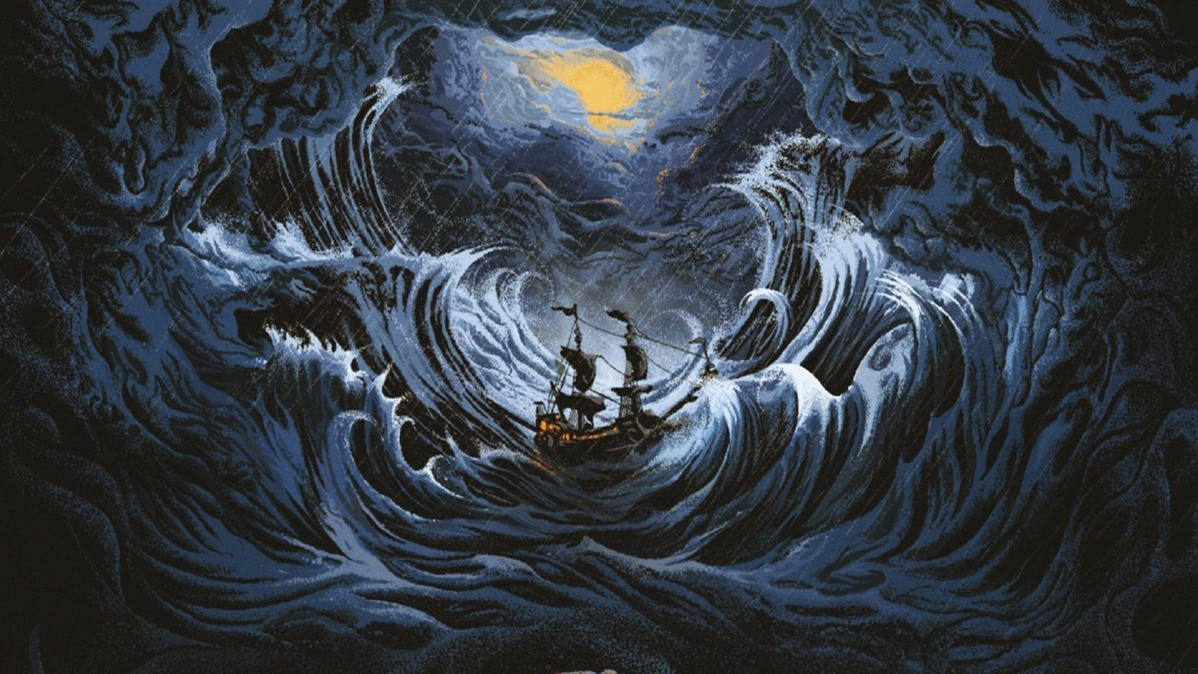

A Sailor’s Guide to Earth

ATLANTIC

8/10

Sturgill Simpson’s third album begins with a maritime lullaby—seagulls chattering, waves cresting, a squall of ambient electronics that’s cleft in two by the tenderness of an upright piano. And then comes the greeting, one that echoes first-time fathers throughout history: “Hello, my son / Welcome to Earth / You may not be my last, but you’ll always be my first / Wish I’d done this ten years ago—but how could I know / That the answer was so easy?”

The album doesn’t hold a lot of easy answers, necessarily, but it does have plenty of right ones. Simpson did indeed welcome his first son into the world mere weeks after Metamodern Sounds in Country Music made him—depending on who you ask—either roots music’s savior or merely one of its abler practitioners. His life has been a blur of alt-weekly headlines, award shows, and tour dates ever since, but it seems the chaos has also offered some clarity: A Sailor’s Guide to Earth is a collection of songs about first things, important things, things from the heart; it plays like a letter home from a sailor to his son. If the waves have their way these two may never even see each other again—so here the father lays it all out on the line, just in case.

That’s the framing device for a collection of music that is bolder, more expansive, and more personal than anything hinted at even by Simpson’s previous, very fine albums. He produced this one himself, and he brings to it both lofty conceptual sensibilities and an ear for music that’s by turns lovely, tumultuous, ebullient, and haunted. The record is sequenced as a continuous piece of music—think What’s Going On or Parade—and unfolds with the purposefulness of a novel or a play. And though the songs are dripping with pedal steel, Simpson—who recently told The New York Times he listens to Stax-era Elvis more than he ever listened to Waylon Jennings—recruits The Dap-Kings to provide both deep southern soul and nautical sound effects, tying to the record’s watery undercurrents.

It’s a heady milieu with room for the tough-struttin’ funk and fatherly advice of “Keep it Between the Lines” (complete with lyrics about staying in school and laying off the hard stuff) as well as a cover of “In Bloom” that’s best described as psychedelic honky tonk. And the album that begins with a lullaby ends in a panic: “Call to Arms,” the frantic closer, is electric mayhem, Sturgill breathlessly railing against war, violence, drones, and ubiquitous cellphones. “The bullshit’s got to go!” he wails, horrified by the world into which he’s brought another human. Yep: sounds like fatherhood to me.