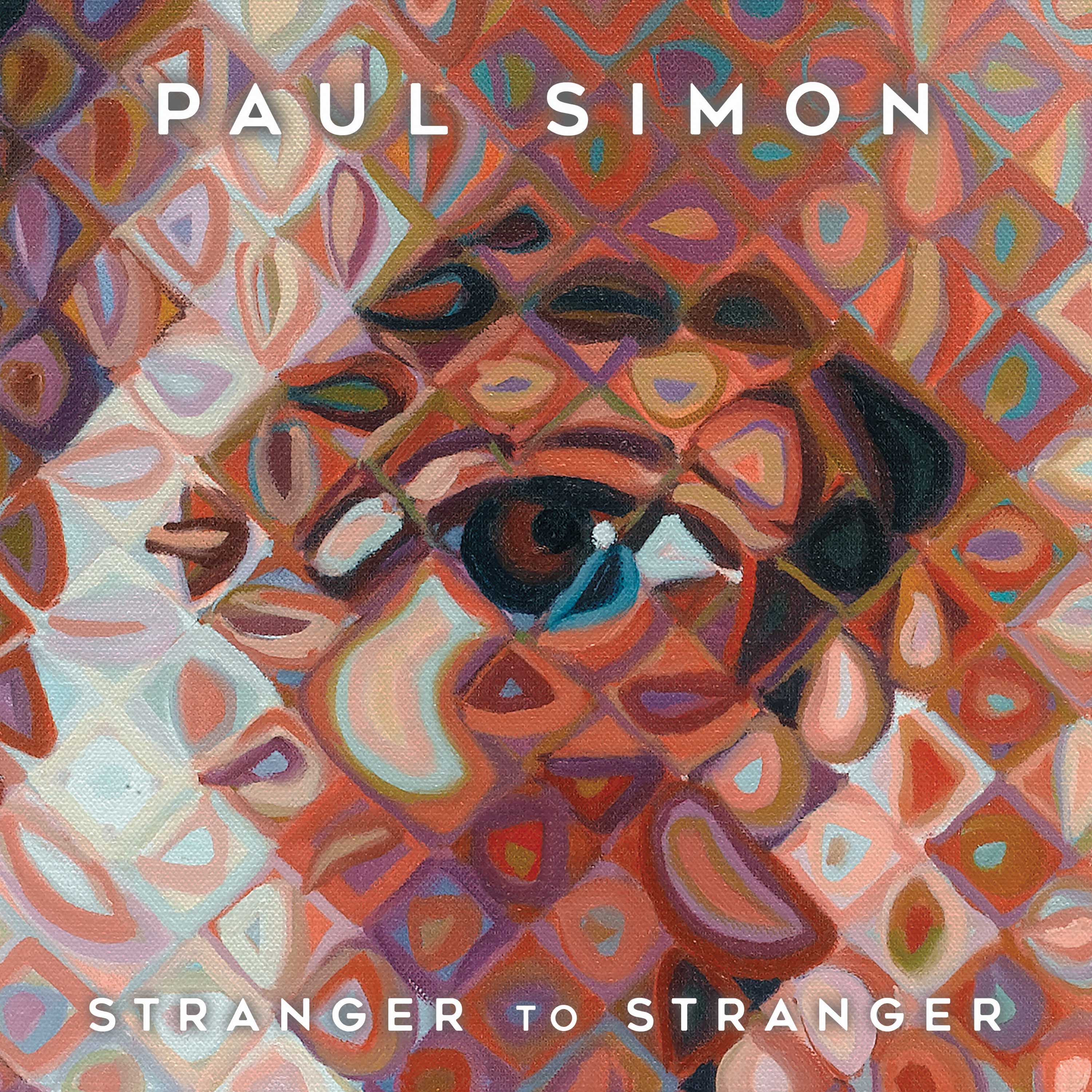

Paul Simon

Stranger to Stranger

CONCORD

8/10

Parades wind their way through Stranger to Stranger not once but twice: first, one character gets caught up in the conga-line rhythms of a song called, fittingly enough, “In a Parade,” but the electric buzz is anything but festive. The song is set against the hustle and bustle of an emergency room; the stakes are high, the prognoses grim. The narrator’s in the thick of it. He’s got his hands full. He doesn’t have time to talk, but the jittery beats say plenty. Three songs later, a song called “The Riverbank” brings the winding processional back into view—only this time, it’s a funeral parade.

That’s to say nothing of all the songs on which the kick of the brass band and the kinetic, confetti-blown energy of the crowd are merely implied, not stated outright. Paul Simon, now decades into his odyssey of fascinatin’ rhythms, has updated Graceland’s percussive bent with a full album of frantic and often finger-poppin’ beats, three of them engineered alongside Italian DJ Clap! Clap! Stranger to Stranger is a heady rush of sound and rhythm, colors and samples—a multicultural mosaic that brings to mind classic-era Public Enemy records, if you can believe it.

And so you have a song called “Street Angel,” with a groove so wide Miles Davis might have appropriated it for his On the Corner sessions. “Cool Papa Bell” bounces and sways to the oom-pah of a tuba, while “Wristband” is a sick little loop of handclaps, finger cymbals, and upright bass. Meanwhile “The Clock” mimics the immaculate metronome rhythms of mortality itself, like the Ghost of Christmas Future suddenly making an appearance amidst the festivities: for all of our parade’s momentum, he tells us, we’ll never outpace the steady march of the minute hand.

Stranger to Stranger is a life and death album, then, and its great achievement is in how it remains playful and engaged and life-affirming rather than moribund or macabre. Simon is alone among his peers in giving each record an identity all its own. He never repeats himself and there is no such thing as a quintessential or “legacy” Paul Simon album—least of all this one, which opens with death imagined as a werewolf, knocking on doors in search of souls to harvest. You can hear his howl in the background, but you almost have to strain to hear it over the mélange of gospel harmonies, clattering percussion, sound effects, and Simon’s own winding, jokey ramble: “The fact is, most obits are mixed reviews / Life is a lottery / A lot of people lose,” he offers, because what else do you say when the werewolf’s coming?

The rush of the music here brings the quieter moments into sharp relief. “Proof of Love” is a God dream, a midnight tangle with dreams and sorrow. And the title tune is a love song: the arrangement is quieter but Simon’s mind is still moving to those anxious beats; words tumble out before thoughts are fully concluded: “I’m just jittery / It’s just a way of dealing with my joy.” Love trembles here with power and vulnerability; joy is precious as the clock ticks and the werewolf comes. That’s what keeps him up at night on “Insomniac’s Lullaby”—but then sleep finds him, and he dreams of parades.