In 1978, the last thing that anyone would have expected from Neil Young was an abstract, stream-of-conscious comic film that touched on issues of nuclear waste and the dating habits of diner waitresses, starred Devo, and would make David Lynch look like Harold Ramis in comparison. “He was hippie Grandpa Granola to us,” says Devo co-founder Mark Mothersbaugh of the music icon. “That was what we thought of Neil before we met him.”

Yet, starting in ’78 and continuing off and on throughout the next three years, Young, under the alias of “Bernard Shakey,” made his narrative cinematic debut as director and writer of Human Highway, a film co-directed by one-time child actor Dean Stockwell and co-written by another former famed teen thespian, Russ Tamblyn. These longtime friends and denizens of Topanga Canyon, along with other pals and habitués of the West LA playground (including actors Charlotte Stewart, Sally Kirkland, and Dennis Hopper, as well as the folkie David Blue), improvised their way through a wonky dreamscape and a sketchy script with Young as the goofball star. The story—roughly, the owner of a diner near a nuclear power plant wants to set the restaurant aflame to collect the insurance money—played third fiddle to the film’s rampant energy and wild ideas. The newly christened Shakey cast himself as the protagonist Lionel Switch, a bumbling, nerdy car mechanic who secretly longs to be a rock star.

“I know he was making fun of himself, but I think that role exposed who Neil really was: a dweeby guy who loved cars and wanted to be a rocker,” says Stewart, whose clothing store on La Cienega Boulevard, Liquid Butterfly, sat across from the offices of Young’s longtime manager (and future co-star), Elliot Roberts.

Human Highway, into which Young reportedly stuffed three million dollars of his own money, had a brief release in 1982 and an equally short run on VHS in 1996. Today, however, with Young having spent decades obsessively recutting it for improved narrative coherence, the film is being rereleased by Warner Bros. Pictures. It now survives as a brisk mini-epic with the director’s colorful vision comparable to that of an early Tim Burton.

photo courtesy of Warner Bros.

She Used to Work in a Diner

Stewart, an alum of David Lynch via Eraserhead and Twin Peaks (“No, I can’t say a word about the upcoming Showtime series,” she giggles), was anxious to work with Young and Roberts. She was a member of a thriving artistic community, owning a store where “wine always flowed” and musicians like Young, Jim Morrison, and Joni Mitchell hung out. She acted in student movies like Lynch’s early American Film Institute work by night and co-starred in Little House on the Prairie by day. “I always thought it was important for professional actors to work with young directors—still do,” she says. Having Young as a novice director, then, didn’t frighten her off.

Stewart was thrilled when Young asked her to play bombshell waitress Charlotte Goodnight, part of a Greek chorus of waitresses and the one with whom Young’s Switch was most in love. “[Young and Stockwell] let us make up all of our dialogue, action, and character development,” she says. Stewart dolled up her voluptuous character with heart-shaped everything (“pins, hankies, earrings”) and spoke in old Young song titles (“Tonight’s the night, baby”). “It was all very improvisational; Neil would give us each scene’s basic thrust and let us run with it. We would do that and then he’d write it down so that the script was penned after the shooting. It was a hoot.”

“We would [improvise] and then he’d write it down so that the script was penned after the shooting. It was a hoot.” — Charlotte Stewart

Kirkland agrees. “It was hilarious,” says the noted improviser, who is known for roles in Anna, The Sting, and JFK, and who just wrapped on the forthcoming The Most Hated Woman in America with another counter-culture great, Peter Fonda. “Dean was a friend of mine and asked if I could come to a Burbank restaurant to meet Neil for some potential film. I went, and there were Charlotte and Geraldine Baron [the third waitress].” Young asked Kirkland her zodiac sign—hey, it was the ’70s—and when he found that she, like him, was a Scorpio, he quickly cast her and named her character “Kathryn.”

“He explained to me that he had this deal with Warner [Bros.] that extended beyond making records,” says Kirkland. “Neil was funny to be around and very professional as a director: so great, helpful, and respectful.” Along with musing on the consequences of her character’s story (“she got fired, so I got to rant and sob”), Kirkland recalls moving location shoots—from San Francisco to New Mexico to the Hollywood soundstages of Raleigh Studios (where a young Kevin Costner was stage manager)—as well as working with Hopper.

By then, the Easy Rider actor and director was earning a reputation as a wild man, and during the shoot he was reportedly something of a drugged-out ghoul. Hopper played the knife-wielding chef to Kirkland’s diner doyenne, and the actress became just a little unnerved by the actor’s blade trickery. “Dennis kept throwing this knife into the wall, then going up to the prop man to ask him to sharpen it—yeah, that got me nervous,” she says. “I asked Neil to ask Dennis not to do this, but Dennis persisted. When I went over to talk to him while he was playing with the knife, I reached up, his hand went down, and he cut my first finger and tore a tendon.” Young instructed Kirkland to sue the production, while Hopper was encouraged to seek treatment. He did, and he thrived going forward. “Dennis and I made amends,” laughs Kirkland. “He even played my husband in [Edtv].”

Q: Are We Not Actors?

Q: Are We Not Actors?

Mothersbaugh was new to Hollywood filmmaking and its stars, let alone drugs and drink, when he met the Human Highway company. “It was weird enough meeting Stockwell and Tamblyn, as I certainly liked their work when they were kid stars,” he says. “They would try to get me to drink alcohol or smoke. I wasn’t having it. And Hopper was even more degenerative in real life than the character he played in Apocalypse Now.”

It was through Stockwell’s then-girlfriend Toni Basil that the whole Topanga troupe got turned on to Devo, as Basil and Iggy Pop had caught the Ohio band’s act in 1977 in San Francisco and led Stockwell to their Devolutionary cause. Devo’s Jerry Casale and Mothersbaugh acknowledge that Roberts had also gotten hold of Devo’s early films. “The first time I saw them with those yellow suits—classic—I showed it to Neil, and he yelled, ‘We need them for the film!’” recalls Roberts, who would eventually became Devo’s manager, too. “We loved Devo. They were the brightest, most creative kids I had ever worked with ’til that time.”

Devo itself originally had mixed feelings about Young. Casale, a one-time-student at Kent State University (as was Mothersbaugh) who witnessed the killing of two of his friends during the horrific campus shooting on May 4, 1970, thought of Young quite poetically. “I may have skewed more to conceptual artists like Captain Beefheart as a teen, but Young’s songs were compelling and his minimalist guitar work appealed to me,” says Casale. “After that massacre, with the whole place roped off like a crime scene, I was lying in my apartment—on Valium, after my girlfriend left—listening to After the Gold Rush.” Combine that with Young’s rush to release the blistering, Kent-centric protest song “Ohio” mere weeks after the tragedy, and Casale was impressed. “To think that nearly ten years after lying on my floor in Akron, listening to him, then working in a Hollywood film with him… Yeah, that was weird,” he notes.

Mothersbaugh needed more convincing as, for him, Young’s albums—“next to those of Cat Stevens”—were the pained recordings he had to endure as a prelude to sex with his teenage girlfriend back in Akron. “I just had to wait for Neil’s album to be over,” he says.

Mothersbaugh needed more convincing as, for him, Young’s albums—“next to those of Cat Stevens”—were the pained recordings he had to endure as a prelude to sex with his teenage girlfriend back in Akron. “I just had to wait for Neil’s album to be over,” he says.

Fast-forward to 1978, and Devo is acting in Human Highway at the request of Young. “When Toni Basil brought Neil to our show, I did not think he was going to like us,” says Casale. “But he loved it, and he told us about this film he was starting.” It wasn’t long until the budding director had won over the skeptical Mothersbaugh as well.

“Here he was making an art film, at the same time being interested in the Sex Pistols and all that,” says Mothersbaugh. “I was a smartass young punk and didn’t appreciate how amazing he was until we started that film.”

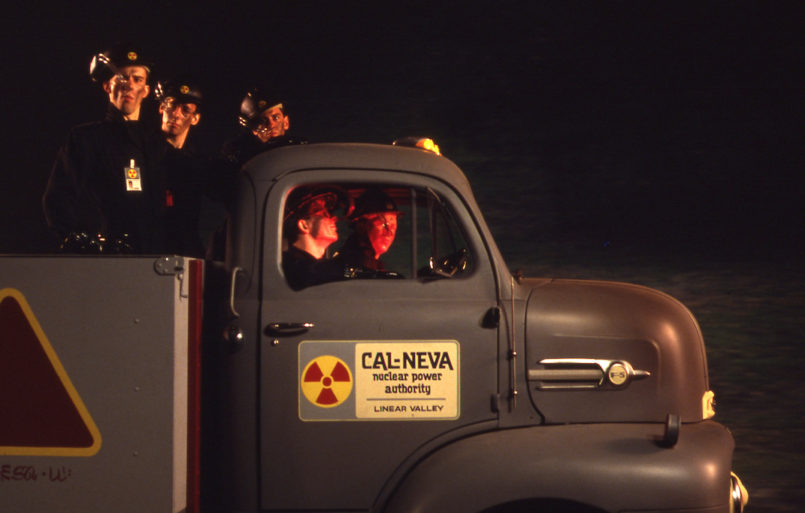

Young would direct Devo as several different characters that he eventually scrapped before having a vision of the band as nuclear waste workers, with Mothersbaugh singing a Kingston Trio parody—snippets of which were filmed by Casale, by then a trusted member of Young’s team. “I was like a kid in a candy store, directing this one segment where we play disgruntled nuclear waste workers unloading this truck full of leaky barrels while driving through the countryside,” says Casale. “One of the barrels came out of the back and took out Neil’s [then-] wife [Pegi Young], who was on the back of a motorcycle. Of course, it was Booji Boy who did the pushing.”

Booji Boy (pronounced “Boogie Boy”) was a Mothersbaugh creation of the time, an odd man-baby played by the singer who sang in a screeching voice and appeared in Human Highway wearing an undersized Devo t-shirt, tight underwear, and a frightening fat-kid mask with Mothersbaugh’s glasses on its face. “Neil wanted us to be in this nightmare sequence where his limo stops at a tan adobe in Taos but opens up to this punk club in San Francisco where we’re singing ‘Hey Hey, My My,’” says Mothersbaugh, still incredulous with the memory. “And Neil’s nerdy-turned-heroic character starts jamming with us. I didn’t want to sing the whole ‘Johnny Rotten’ line—the Sex Pistols had just broken up before this—so I sang ‘Johnny Spud’ and changed several more of Neil’s lyrics. The whole script was like that. Neil just went with it; nothing was pre-planned. ”

Devo had gone from cynical and curious about the squeaky-voiced folkie behind “Heart of Gold” to utterly impressed with the fearless auteur. In fact, the band indirectly contributed to a future Shakey picture when the director used a slogan printed across the butt of the underwear Mothersbaugh had worn as Booji Boy for the title of his next film, a concert-doc he would release in 1979. The slogan came from an ad campaign Mothersbaugh and Casale had come up with for an anti-oxidation product. Several weeks after the Human Highway shoot, Young phoned Devo with an odd question: “‘Hey, do you mind if I use that slogan—“Rust Never Sleeps”—for my next movie?’”

Playing a Part That I Could Understand

Playing a Part That I Could Understand

The first call Roberts received from Young about Human Highway was part of a typical day in the life of a relationship that began in 1967.

“It’s 2:00 a.m.,” Roberts remembers, “Neil’s on the phone and starts talking about this amazing idea until he stops and says, ‘Are you up?’” Young barely waited for an answer before describing the giant sets and the costumes he’d have for his cast. “I stopped him to say that he had to be kidding, that this or that wasn’t doable, but you have to understand Neil. He has these conversations and, usually, all of his projects wind up happening in some form. He did the same thing with Rust Never Sleeps. He sees a thing in his head and figures a way for us to do it.”

“You have to understand Neil. He has these conversations and, usually, all of his projects wind up happening in some form.” — Elliot Roberts

Roberts doesn’t bother questioning costs or production headaches now. The manager states that his closest client comes up with fresh ideas on a near daily basis. “He’s constantly seeking to do something that he’s never done before and the margin of error is usually the same. Human Highway was like that. Stockwell and Russ, both friends of Neil’s, were all living in Topanga. This was the work of a clique.” To hear Roberts tell it, Young’s darker 1970 album After the Gold Rush started life as a Stockwell/Tamblyn script. “Most of Neil’s songs on that album were based upon that script of theirs. They go back that far.”

Putting aside personal reflection to re-focus the spotlight on his client in classic managerial fashion, Roberts offers a single joke about his own onscreen appearance in Human Highway (as, you guessed it, a manager named Whitlow Kingsley) and why he hasn’t appeared in a scripted film since. “They made me a huge offer, you see, as I typically only do still work,” he deadpans before echoing Stewart’s sentiment about Young’s character—that the doofus-y, socially awkward dreamer is a window into his true personality.

Roberts says his favorite scene in Human Highway is the one where Young does his best Jerry Lewis bit up against Stewart’s eye-batting kissy face, which mimics a side of Young that few get to see but that represents a very key part of his method. “He just melts up there—he’s so silly,” says Roberts. “That scene to me was very touching, and very Neil. He just got lost in it.” FL

This article appears in FLOOD 4. You can download or purchase the magazine here.