“I was on the street. This guy waved to me, and he came up to me and said, ‘I’m sorry, I thought you were someone else.’ And I said, ‘I am.’”

It’s one of Demetri Martin’s most popular one-liners, which is saying a lot when you’re talking about someone who’s crafted twenty years’ worth. But after decades spent on stage, from his first shot on Late Night with Conan O’Brien to the inaugural ID10T Fest this summer, Martin is starting to think that he maybe is, in fact, someone else.

“One of the things I love about comedy, especially standup, is it’s really challenging. And the challenges don’t seem to stop,” he says. “But being a parent now, I’m thinking more about comedy that comes out of feeling and emotional experience in addition to comedy of ideas and more cerebral stuff.”

If brevity is the soul of wit, then Martin could be called a tireless soul-searcher. He arrived on the scene in 2000 with a seemingly bottomless supply of dry and absurd insights into everyday ephemera, and he’s kept up a prolific output in the years since. While many comics spend tortured chapters of their lives developing their stage presences, Martin’s was fully formed from the start. He’s always dressed comfortably as he strums an acoustic guitar and offers his bon mots with the gentle delivery of a kid’s show host—though that quiet timbre often conceals an underestimated melancholy, as seen in jokes about being unable to keep a cactus alive.

“I got into this because I like jokes as a way of sharing ideas,” he continues. But his relationship to the stage has evolved. “It gives you a sense of your sensibility as other people receive it,” he says. “You have a live, real-time laboratory along the way. [There are] people telling you, ‘We like this from you, we don’t like that.’”

That lab work has led him to package his jokes in a wide range of containers, from whimsical illustrations delivered both live and in book form, to “remixes” that back his jokes up with glockenspiel accompaniment, to an ambitious couple of seasons of sketches in Important Things with Demetri Martin on Comedy Central. He’s sharpened his voice in the writing room at Conan and as a correspondent at The Daily Show. He was a one-man Twitter years before the platform existed. (“That’s certainly made it a little less fun to do one-liners,” he admits. “Now that everybody’s doing one-line jokes… And, sometimes, doing mine.”)

illustration by Demetri Martin

While his act has changed shapes, its tone has remained stubbornly silly and vaudevillian—in stark and curious contrast to alt-comedy trends over the years. His jokes have stayed short and obtuse despite comedians’ tendencies toward revealing monologues. He’s kept away from irreverence, never getting more personal than his grandmother’s cameo on his 2006 album These Are Jokes, never getting more political than the line “Black people only get three weeks more than sharks in this country.” It’s made him appear to be a bit of a cloud-gazing misfit in the comedy world, as growing pains and rising anxieties make the community and industry very different from when he started.

It seems absurd to pose this question to a comedian, but here goes: Why so silly?

The query comes as no surprise to Martin, who’s quick to count himself among the anxious. “I feel it in the air. I’m terrified, confused. It’s hard to get a foothold on how quickly things are changing, or in some ways devolving.”

But he feels no pressure or obligation to let the fear into his voice as a performer. “When I think of myself as a comedy fan, I appreciate those who can do political comedy and social commentary well,” he confides. “It serves a great purpose in our culture. But I still like daydreaming, and to escape. The combination of that, and that I’m not naturally inclined to make comedy out of politics because I get overwhelmed, those two factors lead me back to where I am now. I’m a voter, and I’m involved as a citizen, but I don’t feel politically compelled comedically.”

Martin considers himself a very different comedian from when he started—not because he’s changed his tone, but because the confidence behind it has changed. “I’m better at being more present in the room. I improvise more, pay more attention during the show, so I’m not just reporting my jokes.”

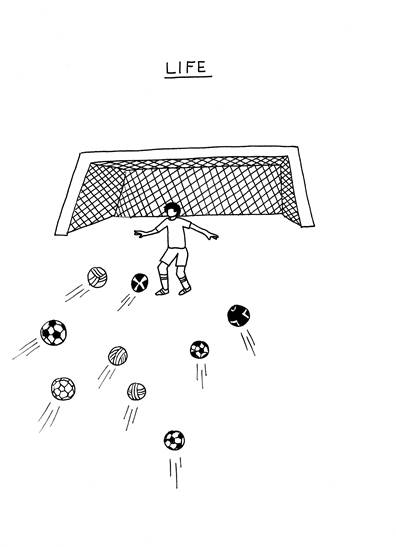

illustration by Demetri Martin

But what of his new interest, for the first time in his creative life, in bringing more personal material into his act? Recent developments have brought meaning to his world far too significant to be contained in one line; he’s a father now, after all, and as of the 2016 Tribeca Film Festival, a filmmaker. His directorial debut, Dean, won the fest’s Best US Narrative Feature Award, and is in theaters this summer. As the writer/director, and in playing the eponymous Dean, Martin built a vessel for all the various elements his act has incorporated over the years.

Pete Dello and Honeybus’s music flows through the film’s shifts between comedy and drama, and Dean’s illustrations convey his internal state as he struggles to process his mother’s recent death. “I saw the screen as a great opportunity for [my] drawings,” Martin elaborates. One particularly poignant split-screen juxtaposes Dean roaming through a party full of strangers with a sketch of him dwarfed among gigantic legs.

Most significantly (and revealingly), as Dean jets between New York and LA in an attempt to escape his mourning, he delivers distracted asides to almost everyone he encounters, as when he waxes philosophical about the lack of burger royalty near a Burger King. Through the lens of Dean and his grief, Demetri Martin’s decades of silly asides start looking more and more therapeutic.

“In my own life, there’s a parallel there. There’s always been some escapist element in daydreaming, and especially in sitting down and writing these jokes out,” he says. In Q&As with audiences and encounters with fans after screenings, Martin faces something utterly new: Rather than just reciting their favorite bits from bygone specials, people immediately share stories of their own losses and relate to the film in deeply vulnerable ways. “In twenty years, I’ve never had something where you’re just instantly having a real conversation with people like this,” he says. “It makes me feel closer to people. It’s felt like the antidote to the social media age we live in, in that we’re connecting over something real.”

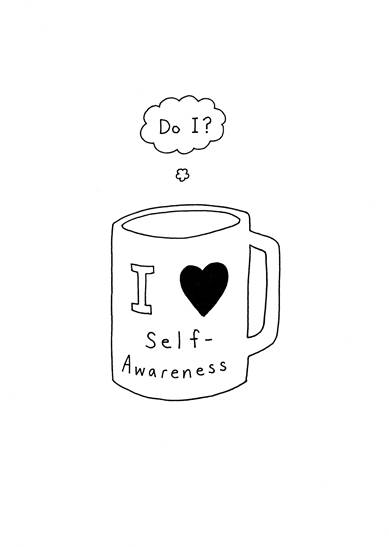

Demetri Martin in Dean

These reactions have turned a new, albeit slightly hesitant, page in Martin’s sketchbook as he develops his new material. “We live in an era of oversharing,” he opines. “What I call ‘diarrhea of autobiography.’ Some people, I do want to hear their stories. But not everyone, and not always.” As he starts turning his absurd observations inward, his confidence turns a humble shade. “Getting a little bit older…and making the movie…I’m drawn more to emotional sources of comedy. I don’t know if I can quite do it yet, but that’s what I’m heading for: a one-way conversation worth listening to. I find that challenging. I do want to give more, if I can, but I want that to be worth [the audience’s] time.” His self-consciousness inspired the name of his upcoming standup tour: “Let’s Get Awkward.”

Beyond his tour dates and set at ID10T Fest, Martin has a new book of drawings called If It’s Not Funny It’s Art debuting in the fall, plans on shooting his next Netflix special for release next year, and is diving into work on the script for his second foray as a writer/director. For now, though, Martin’s new chapter invites reappraisal of the long list of catchy, meme-friendly one-liners that brought him this far. Consider his fan-favorite description of swimming: “Sometimes you do it for fun, and other times you do it to not die.” We can apply that to writing—and receiving—jokes, too. FL

This article originally appears in the FLOOD Festival Guide presented by Toyota C-HR. You can check out the rest of the magazine here.