The comics of Joan Cornellà Vázquez—better known by just his first two names—are immediately recognizable. Their bright colors and simple composition are cheerful and childlike by design, but they’re anything but innocent. Rather, they offer twisted glimpses into the ways of the world, holding a mirror up to the depraved nature of society and confronting issues of sex, religion, racism, and violence in graphic and grotesque ways.

Take, for instance, the cover of his new book, Sot, an image that partially doubles as the poster for the exhibition he’s currently touring across the world. It depicts a grinning man in a green suit holding a selfie stick. Instead of a camera at the end of it, however, there’s a gun. By Cornellà’s standards, it’s pretty tame, but it highlights the essence of what the thirty-six year-old Spaniard’s work is about and how it reflects society at large. Though he’s based in Barcelona, we caught up with Cornellà while he was setting up the New York leg of his exhibition to find out what lies beneath the surface and the shock factor of his work.

You’re travelling around the world with this exhibition, and as a result you’re sort of homeless right now.

Yeah, I’m homeless. I’m a nomad. We decided to do a load of exhibitions—I think there will be eight this year—and I decided to join the team [at Factotum Productions] and paint in every place as I show the works. So I to left my studio and apartment in Barcelona and do this for a while.

How are you finding life on the road?

It’s been just six months, so it’s fine for the moment. I guess if you’re a musician and you do that every day for five years it would be hard, but it’s not as if I’m working every day.

But you are painting as you go along.

Yes, I have no choice! I have to do that.

So how does traveling affect what you do? Do your ideas change depending on which place you happen to be in?

You know, if I get inspiration like this I’m not aware of it. I’m not doing this in a conscious way. And it goes so fast—maybe I spend one month in Hong Kong and another one in Bangkok. It’s not like I’m thinking about [being in those cities]. My work doesn’t work like that; I take more inspiration from the web. We’re living in a globalized world, and it’s not like I depend on real life. I like to spend time in different places for the different cultures and the different people you can meet, and I think that’s why I’m doing this. For my work, I’m not aware of any real inspiration.

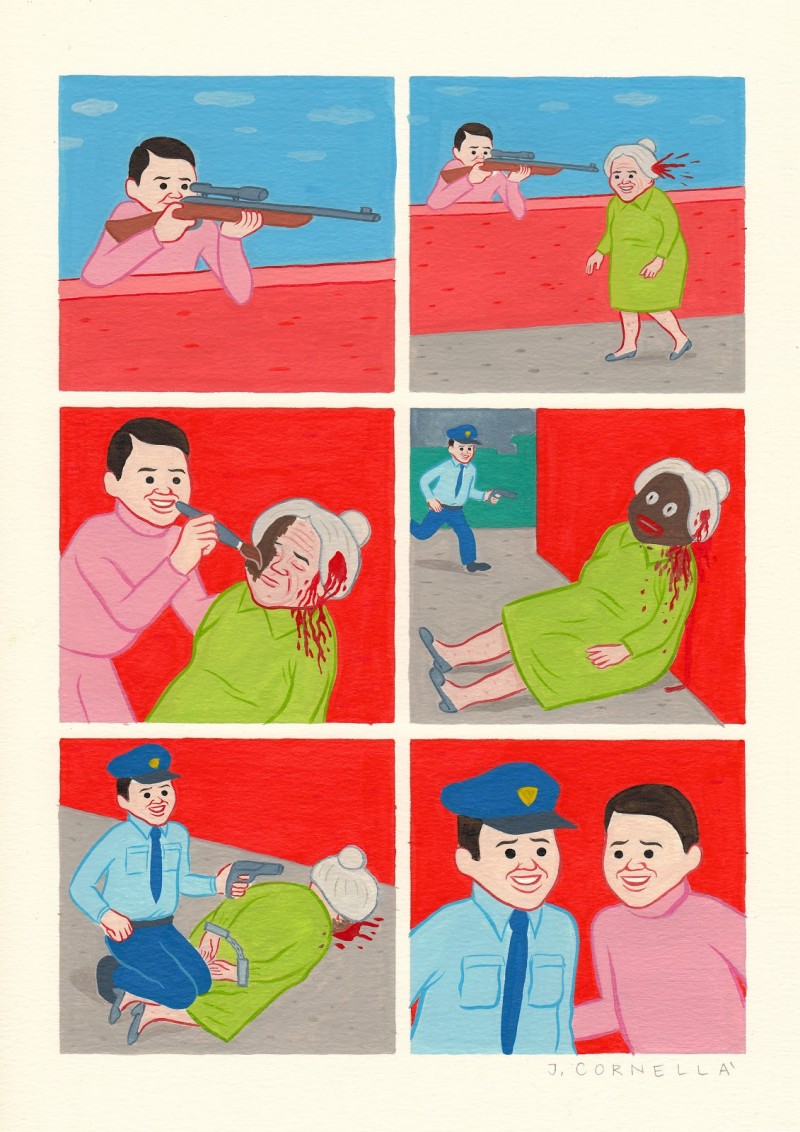

I was asking because one of the first images I saw advertising this exhibition was the one where the woman is shot and then her face is painted black—and in America, police brutality of black people is a very big problem, so I wondered if you were inspired to make that one because you knew you were coming here.

I think a lot of my comics are related to Americans in some sense, but I’m not doing that on purpose. In Spain, we don’t have this amount of black people and this kind of conflict, but it still relates. And it was actually banned [by Facebook]. There were a lot of white people against this comic strip, and then a lot of black people saying, “This is the way it is.” So there was a definite conflict [in terms of response] between white people and black people, but I think that’s good because then you can see how people react—and I guess there’s a lot of racism here. I wasn’t that aware of it—especially in New York, I thought it was less that way, but the more I know about the place the more I’m surprised about it.

Do you see it, then, as your duty as an artist to make people aware of things like that? You’re not one who likes to explain what your art is about.

No, I never do that. But it’s there. At the beginning, I didn’t want my work to be political in an open way. For example, this comic strip we’re talking about, most people were pissed off and they called me racist and they were insulting me and this was maybe three years ago, and most of them were white or Asian and just trying to be politically correct. And in a way I think I’m doing this to fight against political correctness. But my work has a large relationship with violence and things like racism, topics that are so related to the United States. Where I’m from in Spain, we don’t have this kind of violence. Here, everybody talks about it and it’s in your face and they have this problem with guns, but for me, it’s just fiction. I’ve never seen a gun in my life! So I think it is super-related to this place, but because I watched a lot of movies and the United States is part of my culture.

There are people who will look at your work and say that it’s just violence for the sake of violence. Where do you draw the line between making a point and being gratuitous? People often seem to miss the meaning behind the shocking nature of your art.

It depends on the day. I can get pissed off with it, but you have to live with that. There are a lot of people and a lot of opinions and at the beginning I was reading all the comments [on Facebook], but now if I do this it’s a waste of time. I think my work, at some level, is kind of massive, and when that happens there will be some people there just in a superficial way. There are a lot of people who don’t understand. And it’s not like I’m saying “You have to understand this in some way” but they don’t give a fuck. They laugh and they find it hilarious, but because they find it silly. And I would like my work to have some deeper sense.

How have things changed for you since you’ve become more well-known?

One thing is that, at the beginning, there were a lot of people complaining and insulting me, but when something becomes massive, they accept it because a lot of people like it.

Does that push you to be more shocking with your work?

I think so. My work is made for Facebook most of the time, and they ban your stuff if it’s related to sex. But my comic strips that are related to sex aren’t my favorites. They’re fun, but they’re silly. It’s all about religion in the end, [though]. Facebook and the American mentality are religious, especially compared to other places. With the sexual comics, they act like priests most of the time, so I’m trained to fight Facebook.

Which is funny, because you made your name through Facebook in the first place.

Yeah, I owe them a lot. I wouldn’t be here without Facebook. But at the same time I hate it!

You did the cover for Wilco’s last album, Schmilco. How did that come about?

It wasn’t my idea. They came and asked for it and it’s super good for me because it’s promotion. Honestly, I did it for the money [laughs]—and I have to say it wasn’t even big money! FL