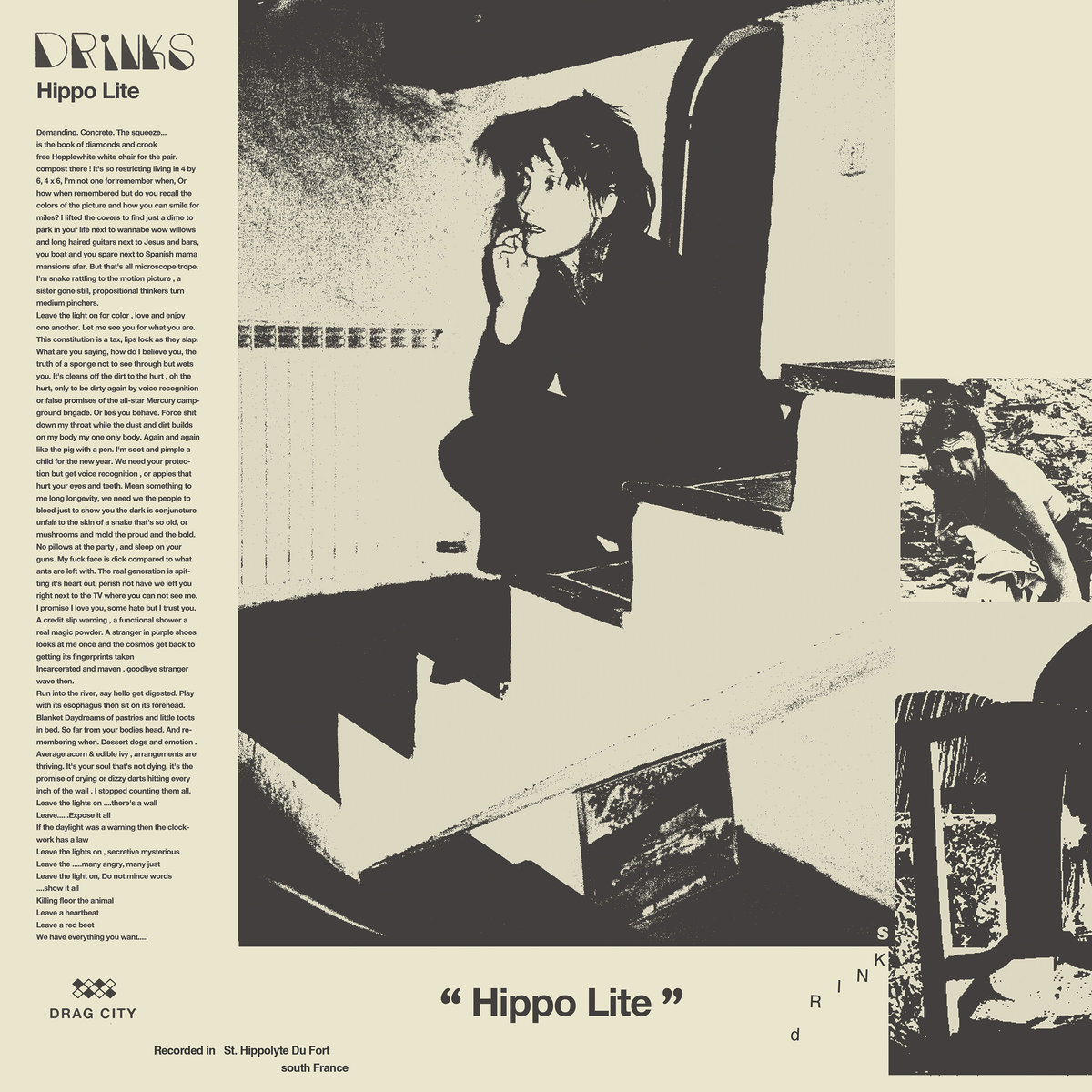

DRINKS

Hippo Lite

DRAG CITY

8/10

Hippo Lite, the second offering from DRINKS—the collaboration of Cate Le Bon and Tim Presley (a.k.a. White Fence)—takes its name from the site of its creation, the commune of Saint-Hippolyte-du-Fort in southern France. Picking apart that name to create an inside joke of a title is just one way in which the duo exerts its creative will upon the time and place in which they have situated themselves, taking ownership of it for their own insular ends. This encapsulates the recursive ethos of Hippo Lite and, to date, the DRINKS project as a whole. The duo perform only for one another and for themselves. To listen is to eavesdrop on intimate, casual conversation.

A record in the truest sense, Hippo Lite captures a moment in time; in this case, a cloistered month of creation, unhindered by expectation and informed by the environment. Employing ambient sounds of France’s nightlife, like frogs and insects, DRINKS put paid to the cliché of setting as its own character: “Any sounds we could think of or wanted,” Presley writes of Hippo Lite’s guiding principles in the accompanying press materials. The whimsy and freedom of players loosed upon river-swimming, day-drinking, and afternoon naps is felt throughout, but the obligations of the outside world loom, even as they indulge in the experience. “What’s on your mind? / Saturation, saturation, saturation, saturation,” Le Bon hoots on “Ducks.”

The freewheeling experimentation of DRINKS’ first offering, 2015’s Hermits on Holiday, remains intact here, sans the fuzzy subterfuge. Recorded by its only outside observer, Welsh musician Stephen Black, Hippo Lite is wholly unstructured and, as such, equally unpredictable. Le Bon and Presley make much with little. Each of the dozen songs turns on a simple concept: a riff, bass line, or turn of phrase warped and subverted by the way it is played, repeated, or spoken. It is in these unconventional choices that Hippo Lite finds resonance, and in this way, a forty-second instrumental like “IF IT” and its creaky two-minute reprise lingers and haunts.

Free of outside influence, Le Bon and Presley’s work feels reflexive, channeling a stream of shared consciousness governed by instinct. They mostly succeed in this by allowing the music to unfold of its own amorphous accord with disjointed lyrics that further obfuscate. “Leave the lights on / Secretive, mysterious,” they sing in unison on “Leave the Lights On,” offering a phrase that could bear the weight of the whole endeavor or serve no purpose beyond the aesthetic. Le Bon’s distinctive voice is put to its best use as an instrument, even while the spare lyrics provide fodder for analysis. On “Corner Shops,” a summation of the record’s best qualities, Le Bon’s vocals meld with bright, off-kilter piano until the two are indistinguishable, much like the interplay between Le Bon and Presley.