I’m meeting with my old friend Wallace Richard Mills at a Mexican restaurant in Downtown Los Angeles, where I ask him one of my favorite first questions: “Give me a Wikipedia definition of who you are.” I guess that’s not really a question, but Wallace supplies some basic information about himself. I will now present that information in the following list disguised as a paragraph:

Wallace Richard Mills is a forty-five-year-old artist. He was born in California. He earned his master’s degree at The School of Visual Arts in New York City. He made art. He hung his art in art shows. Jerry Saltz was one of his teachers. Richard Tuttle was one of his heroes. Tuttle visited Wallace’s studio and totally tut-tutted Wallace’s art. Later, Tuttle retracted his tut-tuts and said that he liked Wallace’s art. Wallace made more art and had more shows, but he felt like an outsider in NYC and eventually moved back to California. Wallace got a job as a cobbler, designing skateboard shoes. He has worked for Sole Tech and DC Shoes, and is currently senior director of product at Supra Footwear. At some point, he got married and had three boys. Art was being created throughout this period, but it was done mostly in secret. He recently bought a Gibson SG guitar. It was on sale for $700.

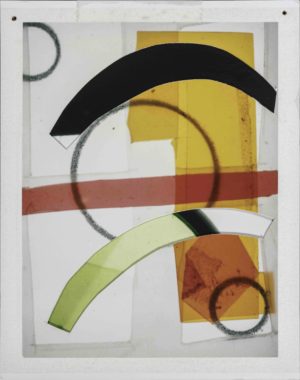

“Untitled”

In case you’re wondering what Wallace looks like, he has a long, gray beard. His hair is closely shaven. He does not smile often, although he seems like he is smiling all the time. His eyes are wise and quiet.

Now that that’s out of the way, we can join back in our conversation. I was in the middle of asking Wallace something like, “Why are we doing this interview?”

“Well,” Wallace says, “now being forty-five, I decided to pull my head out of my ass and actually do what I wanted to way back when I was in my late twenties, which was show art and get out there and do it. I just had a show where the title was BEGIN (again). I was just trying to say, ‘I gotta start this all over.’”

Wallace mentions that some of the pieces in that show—as well as some in the show he’s working toward now, to be hosted at the FLOOD Gallery in LA—are Polaroids, a medium he’s been using since graduate school. His Polaroids are deceptively simple. It’s hard to figure out how they’re created.

“Now being forty-five, I decided to pull my head out of my ass and actually do what I wanted to way back when I was in my late twenties, which was show art.”

“I have this Vivitar machine,” Wallace explains. “It’s from way back before there was digital film, and it was made for photographers on set so they could check to see if their settings were right and if the model looked good and all that. What I slowly started to do with that was make little slides of these abstractions, and then I’d just start playing with it. The result is almost a photogram. But then I’ve been watercoloring on top, collaging, and always fucking them up even further. So it’s like a photo of a photo of a photo.”

Wallace has always created abstract art. I know this because I ask him if he went through any phases where he painted, say, blue clowns. Wallace replies that he did not go through any phases that involved blue clowns. Same with landscapes: no landscapes.

“Two Layer Cake”

When he was a student in New York, he was lucky enough to work at the Guggenheim—he just sold “tickets and shit”—and this position afforded him the privilege of free admission to any of the other NYC museums. He would often visit The Met on his lunch break, find a comfortable spot in front of a piece of art he enjoyed, and just chill for an hour.

“The paintings that I really loved,” Wallace says, “were these non-objective paintings that I’ve always felt kept giving back. Whether it was Ellsworth Kelly or Franz Kline or whatever—I’m not going to barf out a bunch of names—but just all of that stuff was very enriching and I always wanted to revisit it. I fell in love with the language that they had come up with, and I guess that’s what I’ve been trying to build on my own: What’s my Rosetta Stone of symbols and things that I create with?”

“The paintings that I really loved were these non-objective paintings … I fell in love with the language that they had come up with, and I guess that’s what I’ve been trying to build on my own: What’s my Rosetta Stone of symbols and things that I create with?”

I have no idea what he’s talking about. I’m kidding. I know what he’s talking about, although I’m also kind of not kidding. I’m always curious what abstract painters are thinking. What is the meaning? What are you striving for? I’ve stood in front of those paintings before and, yeah, I’ve felt something too, but what does it mean? What does it all mean, man?

“Back when I started painting, I was doing twelve fucking layers of gesso and sanding it to the point where these surfaces were beautiful, but then I’d start painting on it, and I’d start overthinking it, and the thing would just turn into a pile. That’s why I love memos. They’re short little thoughts. Sometimes it’s of something I saw, a shadow I looked at, a repeating pattern, or a weird fucking tequila sign that says, ‘Por Favor.’”

“When I hear the word ‘memo,’” I say, pausing to admire the weird tequila sign that is over my head, “I immediately think of corporate shit: ‘I’ll shoot out a memo!’ It’s interesting that you use it in describing something that’s really supposed to be so happy and joyous—art—because no one likes receiving memos.”

“When I think of a memo,” Wallace replies, “it’s more of a memoir, and that’s where the diaristic side to some of the things that I do comes from. If you’re writing in a diary, you’re usually not belaboring stuff.”

It should be noted, incidentally, that “memo” and “memoir” are cognate. I am not a linguist, but they both appear to be derived from the Latin “memor,” which means “remembering.” So a memo really is kind of a little memoir. I stand corrected.

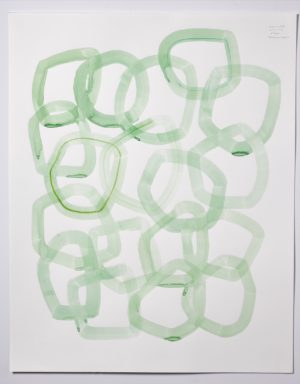

“Chain Link”

One of Wallace’s titles—memos, whatever—that I was immediately drawn to was “Cliff Them All.” Obviously a reference to Cliff Burton (RIP), Metallica’s bassist on their first three albums. What I didn’t know was that Cliff ’Em All is also the title of a documentary devoted to Burton.

“I think the ‘Chain Link’ piece is nice, too,” I say, “because it looks like someone asked a child to paint a picture of a chain-link fence. Picasso said, ‘Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once [they grow] up’—but the little movies that you recently made for this upcoming show kind of look like a children’s program. They’re very primitive. Is that intentional?”

“A little bit,” Wallace says. “More honest, I guess. I was thinking of stop-motion animation. I was doing all these things in my head, but it wasn’t happening and I wasn’t able to get the technical stuff ready to be able to do it. So I decided, ‘I’m going to make what I think I can.’” FL

This article appears in FLOOD 9. You can subscribe to the magazine here.