Chris Frantz is a lover, not a fighter. That’s apparent from the relationship that the drummer and co-founding member of Talking Heads and Tom Tom Club shares with both of those groups’ fellow co-founder, bassist Tina Weymouth. Together as marrieds since 1977, now living in Fairfield, Connecticut with their two sons, Frantz and Weymouth have been a unit since they were art students at the Rhode Island School of Design in the early ’70s, before they both played music, before they befriended fellow RISD student/guitarist David Byrne, and before that trio moved to NYC’s Lower East Side in 1975 to join the area’s burgeoning art-punk scene.

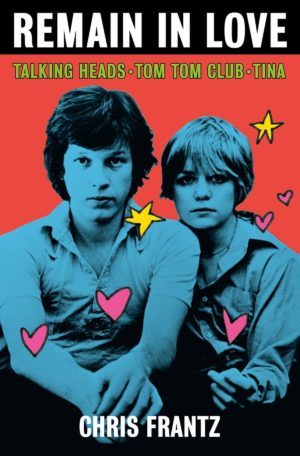

Along with sharing those times in the twilight of punk and the ensemble’s vividly imagined growth along the lines of innovative twitchy Afro-funk and ambient pop, Frantz—in his first memoir writings, Remain in Love: Talking Heads, Tom Tom Club, Tina—portrays the glories of that rise and the joys of friendships made. Frankly, too, Frantz writes how and why it all went wrong with Byrne, how Lou Reed and Brian Eno also sought to fleece Talking Heads in their own ways, and so much more—all while managing to be jovial and justifiably appreciative of all the good that went on with both of his bands and steering commendably clear of gossip. With that, Frantz has created something novel with Remain in Love—it’s seemingly the first-ever gracious and grateful biographical rock read.

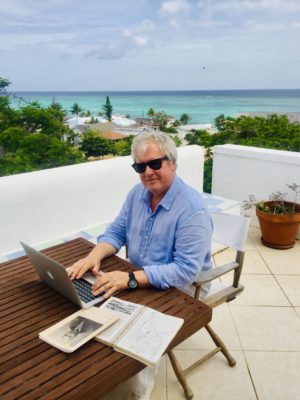

We caught up with Frantz, self-isolating at his and Tina’s home-studio complex in Connecticut, in order to discuss the finer points of love, funk, punk, and marriage.

A majority of Remain in Love is about good luck. You sound genuinely happy and thankful to be part of pretty much everything you do. That’s rare in life, let alone a music biography.

I guess it is. Even though I had a large hand in arranging all this, I’m still thankful. I had long imagined Talking Heads, and had tried to put something like that together for a very long time before it actually happened. I had an idea of what a professional band would be, one that if we decided to go for it would be a completely different prospect. Something less predictable than what rock music had become at that point. Not that I didn’t like a lot of stuff during those days.

See how nice you are. You can’t even dis the music you didn’t want to be involved in.

[Laughs] It’s funny, though. We’re hearing the same thing on the radio now that we heard back then—Elton John, Eagles, Queen. Those are great artists. But then I really thought up a band that was different, apart from that norm. So when I met David, and we started to work together in our little college band, The Artistics, I felt as if that was a very promising thing. It was of my design that Tina came in, and would come along to New York. I had been bugging her for years before that to join my band on any instrument she wanted. I think it was only after she saw David and I struggling to get something going in New York—that’s when she finally had the revelation that she could help us. And she did. Hallelujah. It worked out, and we made our mark. That’s rewarding.

Coming into New York City and onto a block where you were a stone’s throw from William S. Burroughs, Robert Mapplethorpe, John Giorno, and Ornette Coleman—were you a star struck young artist?

You rarely saw them, as they were running around or traveling with their work. They were doing their thing. But you knew they were there, and that was inspiring. We felt part of the tradition of aspiring, young, sort of avant-garde artists. Even though it’s OK to be inspired by people, you also have to dig down deep and bring something of yourself to the project.

“You couldn’t be content to—or want to—copy William S. Burroughs or Ornette Coleman. You had to bring that which was unique to you to your project. I think everybody in Talking Heads did that. Tom Tom Club, too.”

You wanted to move beyond influence.

You couldn’t be content to—or want to—copy William S. Burroughs or Ornette Coleman. You had to bring that which was unique to you to your project. I think everybody in Talking Heads did that. Tom Tom Club, too.

You, Tina, and Jerry Harrison have spoken about wanting to reunite with Byrne. What sort of band do you think you would be, one that would exist only if it created new material, or one that played Heads classics?

Ideally, we would have new songs. Truth is, and I say this with vast experience in the matter, the kids just want to hear the hits, man [laughs]. I guess that would all depend on how much time people would have to devote to this. It does take time, especially when you’re as picky as we are in Talking Heads.

The manner in which you speak about Byrne in the book, I can’t help but hear an innate politeness, even when the topic turns sour. Why pull punches?

David is but one of many interesting characters in the book. It’s not a book about my relationship with David Byrne. We did great work together, fantastic work. Anybody who works together for long periods of time has ups-and-downs. No rock band is perfect, just like no government body is perfect. There were a lot of things that happened that I wished had happened in a different way, but, the end result is a body of work that is remarkable.

It did get on my nerves at times. Was I jealous of David? No way. I have a great life, a wonderful marriage, lots of excitement. I was disappointed at things that I knew were unfair. Part of doing business, making art, means having to roll with collaborators. While I wanted to point out that David had a profound effect on that, so did everybody else in the band. It was a shared experience.

The book is filled with many characters, several of them equally conniving as Byrne. Lou Reed tried to sign you to a production/label deal that wasn’t at-all advantageous to Talking Heads, and Brian Eno tried to snag additional above-the-title album credit on Remain in Light. Was it at all weird seeing your heroes in such a petty light?

Yes, it was weird. Disappointing. With Lou, I’m not sure if he was that aware of what standard production deals were like, let alone the one he was offering us—it’s a boilerplate thing you can download off the internet, now. Maybe his manager tried to pull a fast one. We remained friends with Lou after that. With Eno, I don’t have much contact now—last time we saw him was at a U2 concert in Paris in the ’90s. We bumped into him on the way into the venue, and he told us how when he first heard Tom Tom Club how shockingly good we were. Again, it’s an imperfect world. We just have to find a way to make it work for ourselves.

Your memory is really sharp. The way you portray Eno’s production mysteries are very matter-of-fact, your show dates and reminiscences are always on the money. Did you keep journals?

I did not. I’m kicking myself. I bought notebooks, one being this beautiful leather-bound book in Berlin. I just never wrote in it. I’m pretty sure it’s still blank. I also regret never taking pictures—we didn’t have cameras. We didn’t have tape recorders. It was a different time. Now everyone photographs and records everything.

Tina, however, was our tour manager, and she kept very detailed date books. I paid particular attention to 1977 when we did that tour with the Ramones and made our first album. Hers was a datebook bought at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the 1977 edition had King Tut on the cover—like Steve Martin’s King Tut. She wrote little notes, like name and date of the venue, how many tickets were sold, how many encores we got, and whether or not we did a good gig. Knock on wood, too—I still have a pretty good memory.

“Was I jealous of David? No way. I have a great life, a wonderful marriage, lots of excitement.”

In Remain in Love, what was the least enjoyable part to recall? I was surprised about your drug use, and I don’t know exactly why.

We always kept our drug use under wraps. Some bands flaunted it. We were the opposite. I remember being on a boat in the Bahamas with Joe Strummer and Mick Jones of The Clash, and they were absolutely shocked—just like you—that Talking Heads did drugs. Having said that, we never did drugs while we were recording or on stage. Save it for after the show.

Actually, I didn’t even write about my least pleasant memory. It was the last Talking Heads live show, a festival in New Zealand we headlined with Eurythmics, Simple Minds, INXS, Midnight Oil, and The Pretenders below us on the bill. A super show. Sadly, our last—which I didn’t know until halfway through the show David stomped off stage. I was able to get him to come back on to finish the set, using…shall we say…physical force. I knew then that this was an unhappy ending.

And the most enjoyable memory?

Musically or professionally, it’s when I was walking down Houston Street in New York, walking west toward the corner of 6th Avenue where ten basketball courts stand. It was a beautiful day. Every court was filled. Their boom boxes were out, turned to the hip-hop station, WBLS, when all of a sudden, all of the boxes started blasting out a mega-mix of “Genius of Love.” That was an ‘oh wow’ moment. To my double amazement, all the guys who were playing ball—mind you, “Genius of Love” had just come out in the summer of 1981—stopped, put their balls down, and just started dancing. And for a very long time. I’m pretty sure I had tears in my eyes. This was like such an achievement. That was a very happy day. FL