Lou Reed

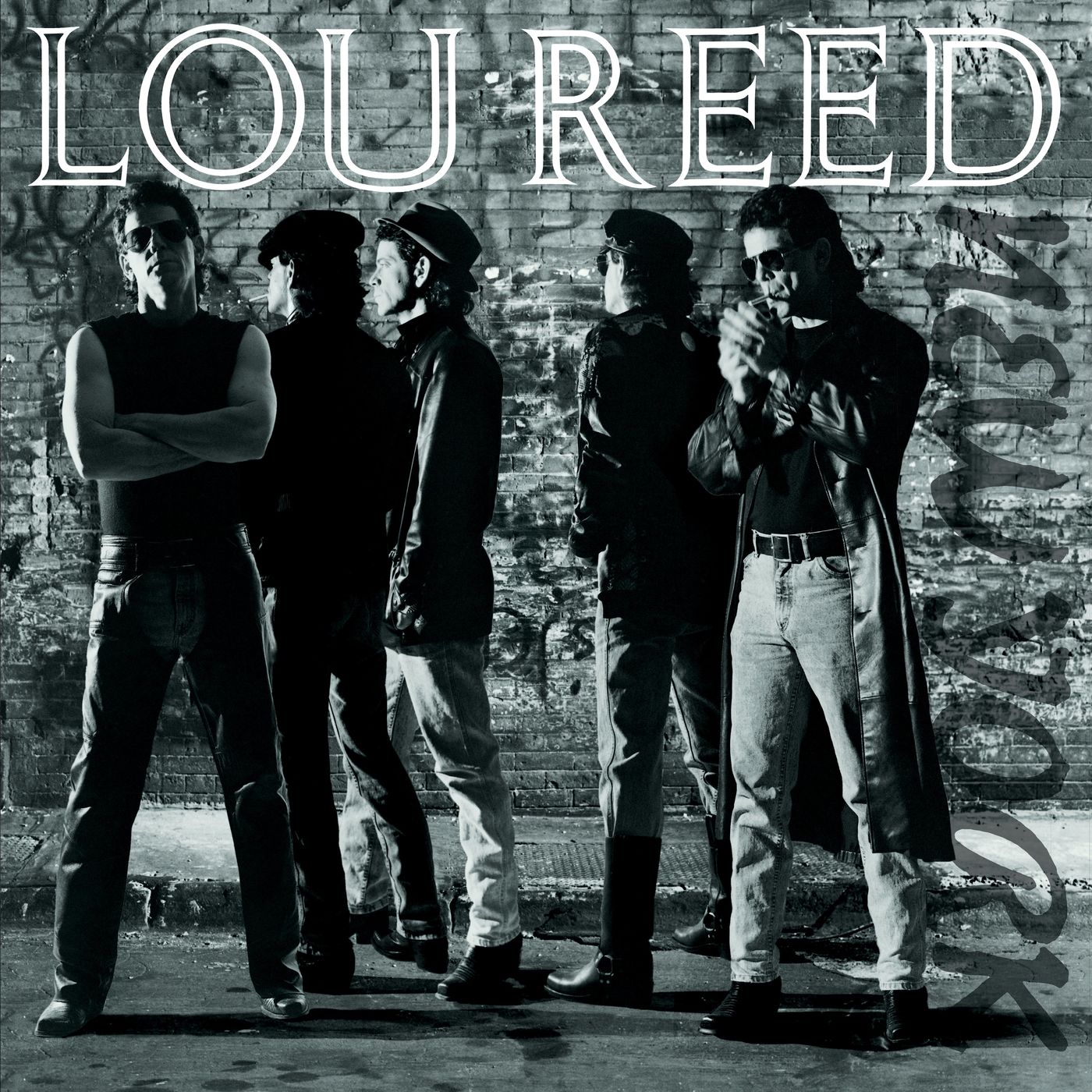

New York: Deluxe Edition (1989)

+

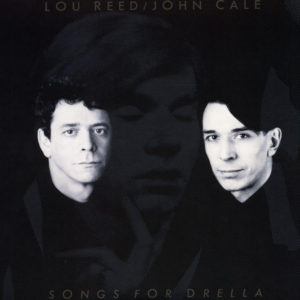

Lou Reed & John Cale

Songs for Drella (1990)

RHINO

Like the town he loved, hated, and covered as often and as vividly as Jimmy Breslin or Fran Lebowitz, the only thing that’s had more ups and downs than New York City was Lou Reed. A rough 1980s for Reed—who hadn’t made an innovative musical or interesting lyrical album since 1982’s The Blue Mask—and New York—a Reagan-manipulated decade of corporate greed, Wall Street excess, and the worst levels of crime in the city’s history—culminated in the death of Andy Warhol, mentor to Reed, pop provocateur who discovered The Velvet Underground, and icon of all the weird beauty, sexuality, and detritus that was NYC.

Whether it was Warhol’s death that inspired Reed—first alone, then with VU bandmate John Cale with whom he hadn’t worked in decades—to move from the mediocrity of writing about mid-life crises and humdrum romance, is uncertain. By 1989, Reed was ready for a change, a renaissance, one where he pared down and made crisp his musical edge while sharpening his poison pen to a journalistic precision with a protestor’s ardor. He was also (reluctantly, perhaps) ready to put aside any acrimony with, and animus toward, Cale and test the waters of nuance and noise, though that détente wouldn’t last long enough for the two to get through a hastily aborted Velvet Underground reunion.

With that renaissance came Reed’s finest post-VU works, both dedicated to the things that made him great, glad, mad, and alive: the pointed guitar rock of 1989’s New York and its incendiary look at current affairs and 1990’s tender, biographical art rock cycle Songs for Drella with Cale. While New York gets the deluxe box set treatment with additional demos, corresponding live versions, and a separate concert DVD this week, the spare and poignant Songs for Drella gets a Record Store Day release three weeks later, a first on vinyl.

Where New York is hardcore sociopolitical local news in a plain brown wrapper—nothing but the cold facts and colder, tangled guitar lines courtesy Reed and Mike Rathke—Songs for Drella is warm with its own level of noisy, avant-garde discordance that it reaches with ease and fire—but is also lovely, supple, bittersweet, and equally experimental in its softness, much like the extremes of that first Velvet Underground album that Reed and Cale made with “producer” Warhol.

The straightforward rock-and-roll of New York, its no-muss-no-fuss bluntness directed by Reed in his liner notes to be digested in one gulp (as if it were “a book or a movie”) spits its bile at a murderer’s row of guilty New Yorkers—Mike Tyson, Trump, Giuilani, Morton Downey, and the “Statue of Bigotry.” Unflinchingly and unsentimentally, the plague that is AIDS is portrayed—like it was—as ravaging and decimating the city’s LGBTQ population and their proud heritage on “Halloween Parade.” Reed’s dry-ice vocals and his bitter, crunching guitars take a drive down the crack-and-smack ridden “Dirty Blvd,” just as he had throughout his VU and solo album past.

Only this walk on the wild side didn’t have a sly winking sensuality that his first solo hit had. This was one stroll that no one came back from alive. And If you’re looking for punch, prescience, or connections to current events, any album that features a white vigilante heralded for shooting four Black teenagers on a subway train without getting jailed, or a young Black graffiti artist murdered by the police with no recrimination, New York is your kind of record. It’s the gutsiest of Reed’s guitar albums since The Blue Mask, with the most cooly impassioned vocals in his career.

Drella, titled after a portmanteau nickname given to Warhol by Reed combining Dracula and Cinderella, is a better album than New York, only in that it contains more radically diverse tones (the plinking piano, dramatic halt, and gentle reminiscences of “Smalltown” and the brooding viola-and piano-driven narrative of “Open House,” for example), textures (the tactile, zig-zagging “Work”), and messages. While “Smalltown” and “Open House” find Reed using a biographer’s fine brush and warm bristly vocal tones to hail his friend and mentor, so, too, does Cale croon with equal tenderness and lilting Welsh verve—even conversational éclat—on “Style It Takes” and “Trouble with Classicists.”

When Cale throws down something talky and narrative, Reed counters with his own nitpickingly chatty “Work” in dedication to Warhol’s motto. That’s the joy of Songs for Drella. Reed always needed a foil, someone to fence with, and got as much of a duel in frission-filling collaborators such as Robert Quine (his co-guitarist on the forlorn and frank The Blue Mask), David Bowie (in his production of the fussily elegant but razor sharp Transformer), and producer Hal Wilner, who took the reigns of latter-day Reed works such as Ecstasy and The Raven and made them as haunting and as haunted as Reed was in real life.

When Cale throws down something talky and narrative, Reed counters with his own nitpickingly chatty “Work” in dedication to Warhol’s motto. That’s the joy of Songs for Drella. Reed always needed a foil, someone to fence with, and got as much of a duel in frission-filling collaborators such as Robert Quine (his co-guitarist on the forlorn and frank The Blue Mask), David Bowie (in his production of the fussily elegant but razor sharp Transformer), and producer Hal Wilner, who took the reigns of latter-day Reed works such as Ecstasy and The Raven and made them as haunting and as haunted as Reed was in real life.

Cale, however, proved to be Reed’s prickliest recording partner, which is why Songs for Drella—like all great newsy storytelling—bleeds and leads ever so delightfully. You could argue that Songs for Drella focused on what made each artist great as a soloist. Take the chamber halt of “Forever Changed.” It’s classic Cale in every way, but listen to that stinging Reed guitar lead. Or Reed’s slow, nerve-jangling “Slip Away” made lyrical by Cale’s dancing, hypnotic keyboard. These men were best when interacting, plain and simple.

As precise as New York, with all the fancy frankness and freakishness of Warhol himself, Songs for Drella portrayed two men in love and hate with their subject and themselves, which, of course, is the sort of angst that shows off Reed at his boldest and brightest. In one two-year period, Lou Reed made more of his artform than most do during their entire careers. That he had several of these periods is what makes him legendary, and his rich catalog worth poring through, over and over.