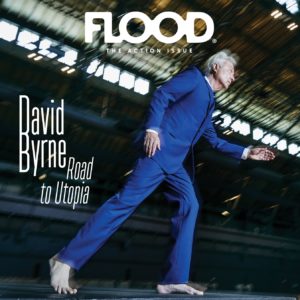

This article appears in FLOOD 11: The Action Issue. You can purchase the magazine here. All proceeds benefit NIVA (National Independent Venue Alliance) and their efforts to save independent venues across the United States. #SaveOurStages

Americans are, of course, politically divided. David Byrne is only too aware. The prolific artist behind the music of Talking Heads has fretted along with all of us as ideological disagreement has caused our country to stumble. We no longer mount meaningful responses to real challenges like climate change and gun violence and racial inequality. Worse, division has eroded the ecosystem of facts that we call reality, making us all feel crazy. And yet, he has faith. Nineteenth century philosopher William James said in the Sentiment of Rationality that faith is the courage to act when doubt is warranted. Has there ever been such a moment to warrant doubt in the American experiment?

A little over a year ago, Byrne launched a web publication dedicated to solutions journalism, Reasons to Be Cheerful—that title itself a statement of faith—looking not to expose more problems with our country, but ways to fix them.

In the run-up to the November 2020 election, he and his editors at the publication are taking an in-depth look at the nature of our political disagreements with a new project they are calling “We Are Not Divided.” No, it’s not about denialism. And they’re not being cheeky or ironic. The package of solutions-oriented stories, to be released five articles per week at Reasons to Be Cheerful and on other partner sites during the two months before the election, explores the theory and practice of overcoming division. It turns out there are loads of people working on this problem right now.

“Every article you read says, ‘Look how divided we are.’ Well, we’re not denying that,” says Byrne on the phone from his Manhattan office, chuckling. He laughs often; he understands how all this must look. “But we’re also saying that there are places and initiatives and institutions that are attempting to bridge those divides and allow people to find ways to talk to one another, and find things in common.”

The stakes are high: a Pew Research Center study from 2019 found that Americans had internalized political division to such an extent that the vast majority saw the gaps only growing wider, and 54 percent of that majority were extremely worried about their elected officials’ ability to solve our major problems. In general, Americans were very pessimistic about their country, and the more divided we are, the less hopeful we become.

But it’s the American way to try to fix things. After the 2016 election, groups appeared such as Braver Angels, which coaches folks on how to talk across the political divide in workshops they call Red/Blue and Bridging the Divide. Solutions like this have proven popular, as lots of people want to get away from the insults slung across the internet and restore the country to a working democracy. When Reasons to Be Cheerful editors Christine McLaren and Will Doig started digging into this phenomenon, they found amazing projects bringing warring peoples together, not just in the U.S. but across the globe.

McLaren, for instance, is writing a piece about how a simple but powerful psychological tool stopped deadly clashes between Muslim youth and anti-terrorist police in the town of Isiolo, Kenya. Activists there asked for help from the Peace and Conflict Neuroscience Lab at the University of Pennsylvania.

“We always think that the people that we are in opposition to think worse of us than they really do,” says McLaren on Zoom from her office in Vancouver. “This has been shown through studies of various different sorts of divided groups of all kinds.” Study after study has demonstrated, for example, that American Republicans and Democrats do not dislike one another nearly as much as they both believe. So the University of Pennsylvania lab surveyed the warring parties in Kenya, and presented the findings on this “perception gap” to both sides.

“Every article you read says, ‘Look how divided we are.’ Well, we’re not denying that. But we’re also saying that there are places and initiatives and institutions that are attempting to bridge those divides and allow people to find ways to talk to one another, and find things in common.”

“Without getting the groups together,” she continues, “they showed these surveys to the other groups, and the other groups were surprised that it turned out this group didn’t hate them as much as they thought. And since that point, there have been no major conflicts between those two groups.”

“We Are Not Divided” explores programs to depolarize college campuses, the neuroscience behind ideology (showing that what we consider to be our core beliefs are actually pretty flexible), and how a new district attorney in Harris County, Texas, turned her county away from its reputation as “the execution capital of America.” One longform piece looks at how Ireland’s parliament brilliantly asked random citizens to consult on its 2012 constitutional amendment process, and how two unlikely participants—a conservative truck driver and a gay IT professional—ended up being friends.

One piece explores the fascinating editing process behind Wikipedia, and how it can be a model for conflict resolution. Some of the grandest battles of the culture wars are taking place across its pages, as editors of all ideological, religious, and academic stripe and persuasion maul one another’s copy, constantly undercutting, subtending, and casting doubt. It’s like a slaughterhouse floor in there.

And yet, research shows that Wikipedia pages created by editors with opposing opinions are of higher quality: more accurate, better-researched and packed with citations, more carefully written. Given a set of constrictions, this friction can produce the most reliable information. “It’s almost like a natural experiment,” says Doig of Wikipedia’s editing structure, on the phone from his office in New Hampshire. “When you force people to work together, even if they might not be people who agree with each other or even like each other, you can end up with some pretty amazing outcomes.”

If that makes you think of American democracy and the way it’s supposed to work, then you’re beginning to see the light. The “We Are Not Divided” project is not designed to sway you to vote any particular way, or to make any partisan arguments. It does end up suggesting that ideological purity probably doesn’t produce good governance, since projects that actually work require compromise.

“I see a risk of people acting out, whatever they’re getting all hot and bothered about,” says Byrne. “We see lots of people do that. They let their ideology—or their various other kinds of rules that they’ve made for themselves, or hatreds, or emotional feelings—override their own common sense. It’s kind of got to get beyond that, to go, ‘What’s really going to work here?’”

We need these solutions, because we need to stop feeling crazy. Byrne started blogging solution stories a few years back, even before the 2016 election, because the regular news was so bleak. “I felt like there was increasing division and a lot of stuff that was getting me kind of depressed, and anxious, and not very hopeful,” Byrne says. “So as a countermeasure to that, I started bookmarking and saving articles I would read. It got a little more formalized over time; I actually made rules for myself. And I realized that it really was helping me, and I think other people really like it.”

In April 2019, he hired staff and Reasons to Be Cheerful was born. The publication had a psychological function right from the start: to offer an alternative to the helplessness inspired by the daily news. It doesn’t go out of its way to cheer you up, per se, but action is just naturally uplifting. The site identifies problems, and then offers the upbeat reality that other people are already dreaming up ways to deal with them.

“The whole journalistic enterprise isn’t just to make me feel better,” he laughs. “I think it also has that effect on other people, and that’s more important. The dream is that, at some point, policy makers and various initiatives or organizations might read about something on our site and realize, ‘Oh, there’s somebody in Belgium, or Canada, or someplace else that has found a solution to this problem that we’ve been dealing with. Maybe we should at least try out their solution.’ The dream is that the project actually has utility.”

Byrne is coming at some of these same issues from another angle in his acclaimed Broadway musical experience, American Utopia, a film version of which, directed by Spike Lee, is due to be released on HBO Max in October. A song-and-dance exploration of the nation’s utopian dreams and potential, at one point in the production, Byrne quotes James Baldwin, saying, “I still believe that we can do with this country something that has not been done before.” Solutions journalism could be an experiment in that direction.

“We [journalists] tend to focus on this ‘sunlight is the best disinfectant’ sort of model, right?” poses McLaren. “That the only way that you hold power to account is by focusing on the negative.” But if you devote serious journalism to solutions, she adds, “you are empowering citizens with information that they need to hold people to account, because you’re enabling them to understand what alternatives could look like. Even if it’s not something that can be perfectly copy-and-pasted, you’re giving them the understanding of how things actually can move forward, which is just as empowering as telling them what’s wrong and who’s messing up.”

“The whole journalistic enterprise isn’t just to make me feel better. I think it also has that effect on other people, and that’s more important.”

Doig points out that the non-stop flow of doomy headlines, which sell a lot of newspapers, presents a skewed version of the world, a disaster every day, when our lives aren’t really like that. We laugh together, we act out of love, public utilities and administrations continue to function at some level, and good things happen. “In some sense, it’s a vicious cycle. Because by only reporting on everything that’s going wrong, not only are you providing an inaccurate picture of the world, but you can make things worse.

“For example,” he continues, “when all you read about is how our institutions are failing us, not only is that probably not accurate, but then it decreases people’s confidence in those institutions. That decreased confidence then weakens those institutions even further. So, it becomes a downward spiral, where the worse people think things are, the worse they can actually become.”

“And that has a major impact on your ability to go out and enact change on the things that you care about,” adds McLaren. “If you feel like there is no hope, then you’re going to act that way.”

Byrne points out that living in NYC during the coronavirus pandemic has led citizens to some hopeful adaptations. For one, everyone’s biking. Well known for eschewing cars and cycling everywhere around NYC, Byrne now has lots of company. He feels like a certain proportion of them won’t go back to driving a car now that they see how easy it is to get around.

Maybe that hasn’t happened as much in other cities. But becoming a nation of cyclists would be good for our carbon footprint, for air quality, for a healthier citizenry. So it could catch on. NYC, as big as it is, could be a microcosm of the rest of the country.

“The idea of a microcosm, I think, is really important,” says Byrne. “If you can do something on a small scale in one location, then there’s often the possibility that it could be copied or cloned in other places. It’s not like you have to solve the world’s problems or the problems of a huge nation instantly, if you can get a local solution. Maybe that then can be scaled up, or copied, or imitated, or modified, or whatever. It doesn’t have to be that you change everything overnight. It can happen in a way where people adopt different ways of doing things because they see that it works.”

Talking, really talking, is the cure we’re all seeking, and Byrne leads by example. In his writing on Reasons to Be Cheerful, he’s clearly partisan, but he protects the rights of other people to respectfully disagree. The problem with social media and most of the internet, I’m sure we can all commiserate, is that it’s a bad place to actually talk about anything, except maybe puppies and kitties. The very algorithms that run these sites reward extremes, driving us to shouting and ugliness. They’re designed to bring out the hate. Reasons to Be Cheerful is a safe space by comparison.

Byrne’s writing has sparked a few good discussions, including one about nuclear power: In response to a piece he wrote in which he mentioned that nuclear power was not safe, his frequent artistic collaborator Brian Eno wrote his own article supporting nuclear power, citing British environmental hero George Monbiot, and eliciting a contribution from Whole Earth Catalog founder Stewart Brand, who cites pro-nuclear enviro Michael Shellenberger. No one gets shouted down. It feels like a rational discussion amongst people who don’t care about being right, but care a lot about getting the answer right.

“It’s not like you have to solve the world’s problems instantly, if you can get a local solution. Maybe that then can be scaled up, or copied, or imitated, or modified, or whatever. It doesn’t have to be that you change everything overnight. It can happen in a way where people adopt different ways of doing things because they see that it works.”

That spirit informs the “We Are Not Divided” project, even if Byrne’s not doing a lot of writing. Maybe not any. Instead, he’s doing a series of drawings that will serve as illustrations for the project. He says he’s not drawing on specific topics, just drawing, and he’s leaving it to McLaren and Doig to figure out where they go.

He’s also releasing a song that he wrote for a musical about Joan of Arc. The song is based on Bible verses from 1 Corinthians 12, in which the Apostle Paul teaches that, just as no part of the human body can simply get rid of the others, the church is a whole made up of all its members. In the King James Bible, verse 21 starts: “And the eye cannot say unto the hand, I have no need of thee: nor again the head to the feet, I have no need of you.” In the context of Joan of Arc, that line represents the church leaders telling her to submit to their authority. But in the context of our current political moment, the metaphor of the body working together means something different. Even liberating.

“In the moment that we’re in now, the song, and the Bible verse, really is about how in order to survive, we really do have to work together,” he says. “It has a completely different meaning, but it really works.”

We really aren’t divided. We’re a whole, and the whole thrives or fails together. Now that you know where to start making a difference, go on. Dig in. FL