Long before they turned their VP Records label and distributorship into a worldwide, independent empire with offices around the globe moving all forms of Caribbean music, past and present, Vincent “Randy” Chin and his wife Patricia “Miss Pat” Chin ran a full-house recording studio, Studio 17, and a record label. Opening in Kingston, Jamaica before moving to Jamaica, Queens, the Chins—who eventually placed everything under the VP umbrella—were two of the first people to produce, manufacture, and sell homegrown artists to Jamaican audiences by the likes of John Holt, Alton Ellis, and Lord Creator. The Chins had a house band, Randy’s All-Stars, that included keyboardist Augustus Pablo, Wailers bassist and keyboard player Aston “Familyman” Barrett and Tyrone Downie, and drummer Sly Dunbar. Lee Perry recorded some of Bob Marley and the Wailers’ first tracks there, as did eventual reggae superstars Dennis Brown, Gregory Isaacs, and Johnny Nash.

That they were able to repeat the same trick in New York City may not have made Vincent happy, as he missed his homeland, but here, his wife Miss Pat thrived to become the First Lady of Jamaican music—from ska to reggaeton. Once here, VP became the largest reggae record company in America (especially after its acquisition of Greensleeves Records and its distribution/marketing partnership with Atlantic Records), with Miss Pat continuing on in her role, even after her husband passed in 2003.

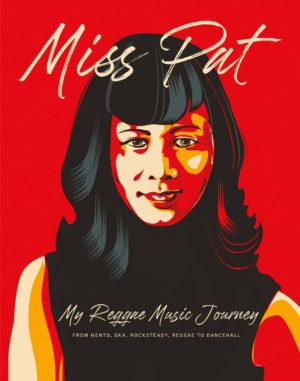

For all this Miss Pat has a world of memories to go with her present and future plans (yes, at 80-plus years old she still goes into work everyday) and has created a gorgeous coffee table book/completist memoir titled Miss Pat: My Reggae Music Journey. The colorful, large-scale tome not only tells the tale of Miss Pat’s life with her husband and how reggae was made and sold in the Chins’ image, but also the story of a strong woman in what was once considered the boy’s club of the record industry. We caught up with Miss Pat while on a break from her VP duties.

You started doing this when you were 18, yes?

Yes, with my husband. That’s a lifetime. I wanted to share that lifetime, the struggles and the joys with people, which is why I wrote the book. I took my time writing it—four years. Originally I only meant it to be a scrapbook for my great grandchildren and the children to come. It turned out to be a nice portrait of what it meant to be a woman going through what I went through, as well as the struggles with my husband.

Does one struggle stick out for you in particular?

When we came to America from Jamaica, he was very depressed. He had left his home country, his friends, and his way of life. When dancehall came around, I guess he didn’t appreciate it too much. It wasn’t his thing. I watched my husband fade away from me. It was a hard time for us, but, thank God, we had the music and the musician friends who made those records. I wanted to share those dark times—maybe times that my family didn’t know about.

You said your husband didn’t like dancehall. Did you?

I was able to sell everything that came around. My husband was the producer and studio builder. I learned to adapt, whether it was the ska of our start through to riddim and into the present. If the public liked it, I learned about it. No style of music ever bothered me. I was happy when the public was happy. Change in music is what people required.

Your husband knew how to make Jamaican music sound authentic, pure, and clear before anyone. He produced it, but you marketed and sold it.

“If the public liked it, I learned about it. No style of music ever bothered me. I was happy when the public was happy. Change in music is what people required.”

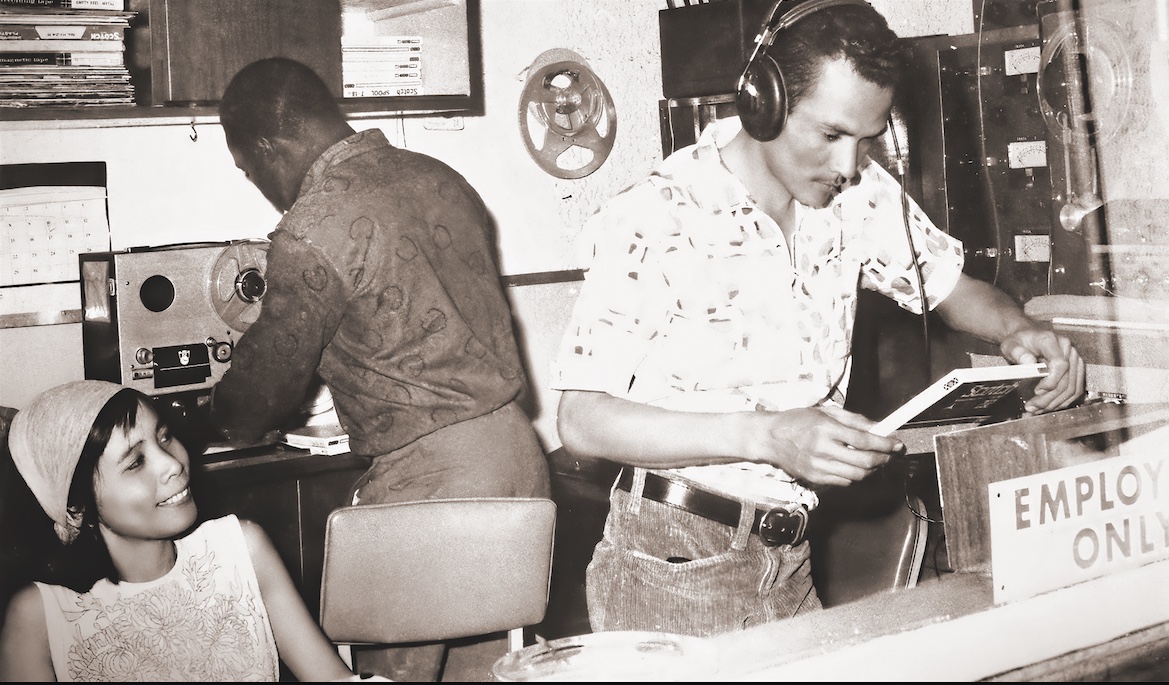

The studio that my husband built, he made it so that you could hear every instrument, every voice. That wasn’t true of all Jamaican music before him. But he made sure it was soundproof, especially as we were running a record store downstairs. We blasted records seven days a week in that store with me at the counter 24/7.

When we first got to America, Vincent used to hang at all the jazz clubs. He loved jazz. I believe he used that in making his sound for the studio, got all the best sound men from those clubs. You know what he was proudest of though? His organs. He had three organs in that studio, especially that big Hammond. That’s why people far and wide—Johnny Nash, Bob Marley—recorded there. Plus, the advantage we had was that artists and producers could record with us, mix it, and make a dubplate right there, and then play it in the store where the people who were buying your records could hear it. All in one day.

VP Records isn’t just an epic Jamaican music label of the past, it’s equally crucial to the marketplace of the present. What makes VP different from other Caribbean-based labels?

We stock and produce everything. Like the store, I bought every producer and labels’ product to go with my label’s product. For example, when I came to New York 40 years ago, soca was a big thing. I had to learn quickly about soca, what was good, and sell other producers’ soca as well as making and selling our own soca. If you don’t have it, people will get it somewhere else. My company stays in the forefront because we adapt, musically change with taste and time. I had to learn about digital and streaming just as I had to learn about CDs after vinyl.

What do you think, during your time in New York, of Jamaican music taking on more American flavors or idioms such as hip-hop and pop, then vice versa?

I like it. Traveling all over the world as I have, I’ve witnessed young people learning to love reggae more because it’s mixed with popular music that they already love. Also, the kids in their twenties, I notice, are going backwards. They’re learning about, buying, and streaming the history of this sound, where this music started and with who. It was the people that made Jamaican music a hit. Critics and labels were not often enthusiastic about reggae 40 years ago. I’m happy to know that, now, reggae music has circulated and continues to do so.

You don’t play favorites in the book, so I’m going to put you on the spot here. Were there artists who you took to more than others?

Over the years, I think my best relationships were with the producers such as Bunny Lee, Gussie Clarke, and Lee Perry. They were the ones who were around when we started, and who were just the nicest people. Maybe we gravitate to the older producers because they understand the business more than the young ones. The older ones know—you put out 10 records, you’re bound to have one that doesn’t sell. The younger ones know only about the hits, not about the flops.

In the book, you make it seem as if making money was like a curse word, and that Marley and Perry were often dissed for showing commercial ambition.

Fifty years ago, my husband didn’t have a lot of money with which to create a studio room or a sound board. He would substitute household items for studio equipment to make the music he wanted to make. Artists who wanted to sustain their career had to be conscious of money and how they spent it. They needed hits to pay their bills. Marley and Perry used the studio, but Marley was shy. I did know he had passion and heart.

“Traveling all over the world as I have, I’ve witnessed young people learning to love reggae more because it’s mixed with popular music that they already love. The kids in their twenties are going backwards. They’re learning about, buying, and streaming the history of this sound, where this music started and with who.”

Lee Perry—is that space cadet act really him?

I’ve known Lee Perry for over 60 years. He’s the same way now as he was then. I had lunch with him three years ago when he played in New York City on his last tour. Same man. All decked out with green and blue hair and tattoos. His lifestyle became his career. He chose a different path, but that’s a path he’s walked forever.

I would be remiss if I didn’t ask you about the great souls that Jamaican music lost in the last several weeks alone: Bunny Wailer, U Roy, Toots Hibbert. What did those people mean to you?

And Bunny Lee, too who passed away in 2020. He was like family to us. I saw Bunny Wailer in January 2020 before the pandemic took a big turn. He was such as beautiful soul. He was so pleasant, so happy. With age, he turned out to be a beautiful person. I think he reached a peak in his life where he had so much graciousness inside of him. We spent so much time together. We were so sad when he passed.

U Roy, we spent a lot of time together when he was making hits. I had a lot of respect for him. He used to come around all the time. And Toots, we were with him when VP held the Jamaica Jamaica event where he gave away his first guitar to put in a museum. He was such a darling. It breaks my heart just thinking of him. I’m so glad I have these memories of them.

“I’ve known Lee Perry for over 60 years. He’s the same way now as he was then. I had lunch with him three years ago when he played in New York CIty on his last tour. Same man. All decked out with green and blue hair and tattoos. His lifestyle became his career.

Sixty years in, do you still love the record game?

More than ever now. Because I have a deeper, longer reflection as to how it started, from such humble beginnings. I still feel happy for artists when they succeed. I’m pleased that many of my children and grandchildren have decided to become part of the business. I’m happy that Byron Lee picked up an electric bass and changed the sound and vibration of Jamaican music. I’m happy that so many of our artists have become like family—often they’re not like they are on stage, but instead so quiet, so humble and respectful. I love that reggae music is played all over the world and continues to grow and change. I’m happy that I’ve had 60 years of this in which to reflect.

You wrote about struggle in Miss Pat. What was the most joyful thing you had the opportunity to write about?

Probably opening Randy’s in Jamaica when we were young. To see how we all made something beautiful based on the pride of our culture—Jamaican reggae music. We didn’t have a culture before reggae music. I’m proud of the 20 years we had there, sharing life with my husband, the producers, musicians, and singers. That was my happiest time. When we came to America, it really was hard for the first five years. I felt as if I was going backwards. I didn’t want to open my mouth because I’m talking Jamaican but watching people look at me and wonder, “Why is this Chinese woman selling me Jamaican music?” I was an outsider. I still am. But I’m accepted now. Truly respected. I deserve it. FL