DMX loved my orange pants. Whenever I hear one of the late rapper’s songs, catch one of his movie clips, or see something online about him, I always think about my orange pants.

I was one of the first people to interview DMX. I’d been following the Yonkers rapper for years and had been anxious to talk to him. In the early 1990s he’d been signed to Ruffhouse Records, which propelled Cypress Hill, Kris Kross, and the Fugees to superstardom. But DMX’s 1993 single “Born Loser” was met with little fanfare and he got dropped from the label.

In December 1997 his star was rising thanks to his head-turning appearances on songs from LL Cool J (“4, 3, 2, 1”), Ma$e (“24 Hrs. To Live”), The LOX (“Money, Power & Respect”), and Mic Geronimo (“Time To Build,” “Usual Suspects”). His off-kilter flow and gruff vocals made him distinctive and dynamic, so I pitched XXL magazine and got the green light to interview him. Irv Gotti connected us.

During our interview, it was clear DMX was ultra-motivated to succeed. Indeed, his passion is what stands out to me about our initial conversation. “It’s been time for me to shine,” DMX, who was 27 at the time, told me back in 1997.

My DMX profile ran in the March 1998 issue of the magazine. By that time, he’d locked in appearances on the remix of Ice Cube’s “We Be Clubbin’” and the title track of Onyx’s Shut ’Em Down LP, as well as a starring role in Hype Williams’ debut feature film Belly. He catapulted to superstardom from there, with his gritty cut “Get at Me Dog” setting the stage for his ubiquitous “Ruff Ryders’ Anthem” single, which made him an A-list rap talent. Before his debut album came out, I told my editors at the Los Angeles Times how popular DMX was going to be. In 1998, he became the first artist in music history to have his first two albums (It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot and Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood) come out in the same year and both debut at #1 on the Billboard album charts. DMX was now a bona fide superstar with more than six million album sales to his credit.

As the rapper ramped up for the release of his third album, …And Then There Was X, I pitched my editors at the LA Times a feature on DMX. They agreed and I went in November 1999 to meet him on the set of the UPN television program Motown Live. I was wearing a Mobb Deep Murda Muzik T-shirt, grey K-Swiss shoes, and orange pants. As we settled in the dressing room of the Hollywood studio where the show was being taped, I noticed that DMX kept looking at my pants. But when he saw what was on the news, his focus shifted. Police officers were removing pit bulls from a woman’s property in Compton, and DMX was upset.

“People that are really living, that are suffering, that are really going through it, they want to hear it because that might stop them from popping you in the head, stealing your bag. Just the fact that someone feels their pain [is why they listen to me]. Here’s your problem magnified, and now you no longer feel alienated for having that problem. Your problem has become the world’s problem.” — DMX, 1999

“They’re taking her babies,” he shouted at the TV news report about illegally housed dogs. “Whoever’s dog that is, they’re going to be sick.” DMX had had some of his dogs taken from him in the past—it was something that stung for him to see. As he shuffled between homes and living on the streets, DMX found kinship with dogs. He famously got a large tattoo on his back reading “One Love Boomer” to memorialize a deceased canine.

“If people were like dogs, the world would be a much better place,” he said in the raspy voice that made his raps instantly recognizable. “Dogs only want to eat. They don’t want their food and their territory invaded. Other than that, they leave you alone. That’s life. Eat, sleep, do what you’ve got to do. Your dog will die for you. You can beat your dog and your dog will see you in a predicament where you’re about to lose your life and your dog will be right there for you. That’s how dogs get down, unconditional love. Humans are not really capable of unconditional love.”

As rap exploded commercially in the 1990s, it became a cultural juggernaut. The gangster rap of Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg changed the music’s sonic direction, while the commercial appeal of the Fugees, the rage of 2Pac, the boundary-pushing of OutKast, the rowdy bounce of Master P, the stylistic brilliance of Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, and the sage street storytelling of Ice Cube, Scarface, Nas, The Notorious B.I.G., and Wu-Tang Clan helped rap expand.

For his part, DMX brought an unflinching take on morality, religion, and justice to rap. He featured prayers on his albums, and typically closed his concerts with one. Although he wasn’t known for his hard-to-decipher rhymes or rhyme patterns, DMX connected with listeners through his ability to tap into a person’s spirit by exploring the inner battles we all wage with ourselves on a daily basis. He made no apologies for being a lost soul struggling with the positive and negative aspects of his character.

“People that are really living, that are suffering, that are really going through it, they want to hear it because that might stop them from popping you in the head, stealing your bag,” he said to me in his Motown Live dressing room. “Just the fact that someone feels their pain [is why they listen to me]. I share with them and I soak it up and spit right back. Here’s your problem magnified, and now you no longer feel alienated for having that problem. Your problem has become the world’s problem.”

“People needed a rebel, and that’s what that dude is putting out there. That’s what people look at him like… People were looking for another Tupac, and [DMX] came along and he had that sort of energy and attitude about him. There was nobody else like that.” — Cypress Hill’s B-Real, 1999

That feeling of connection is what I believe made DMX a lasting artist. …And Then There Was X was his most popular album, selling more than five million copies thanks to the hit singles “Party Up (Up in Here),” “What These B*****s Want,” and “What’s My Name?” It was poignant, wild, and rowdy.

“People needed a rebel, and that’s what that dude is putting out there,” Cypress Hill’s B-Real said to me about DMX back in 1999. “That’s what people look at him like… People were looking for another Tupac, and [DMX] came along and he had that sort of energy and attitude about him. There was nobody else like that.”

When I got word that DMX had passed last week at age 50, it hit me hard. I got to speak with him before he broke through, again as he ascended to superstardom, and occasionally when I’d see him on the road. I got to see how people initially dismissed him, then looked at him as a rap god, then as a person wrestling with drug addiction, and ultimately as an icon during his Verzus rap battle with Snoop Dogg in July 2020. It was a dramatic evolution of how people viewed DMX, but from what I could tell, he remained the same person, a supremely talented artist wrestling with his demons and sharing that experience with the world.

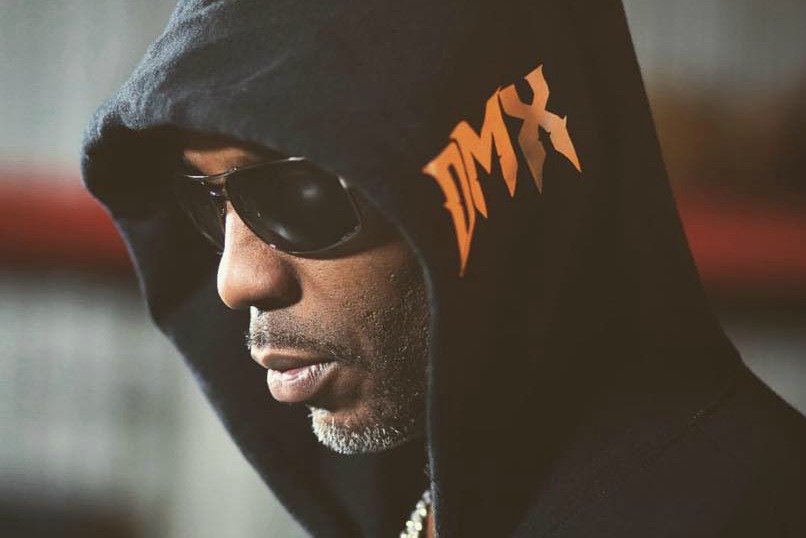

Soren Baker and DMX in 2014

I thought about how much I loved listening to his music, how intense he was every time I met up with him. I remembered his power on stage, whether performing in venues large or small, and how his devotees gave their affirmation with cheers, shouts, and barks. DMX was a passionate person, someone who poured his emotions into his music, his stage show, his acting, and his commentary.

Millions of people connected with his music. I did, too, but DMX and I also connected over my orange pants. He often looked at them during our interview at Motown Live, which lasted about an hour. As we wrapped up, he wanted to know where I’d gotten them. They were a gift, and I told him that I didn’t know. He seemed disappointed, as if he would have gone to get a pair as soon as he was done performing at Motown Live. But since I didn’t know, we ended up talking about life, rap, and dogs before we embraced and went our separate ways.

I left that day as impressed with DMX as ever, and I’d get to speak with him, write about him, listen to his music, and see him perform several more times over the next 20 years. Every time, I think about how much we both loved my orange pants. FL