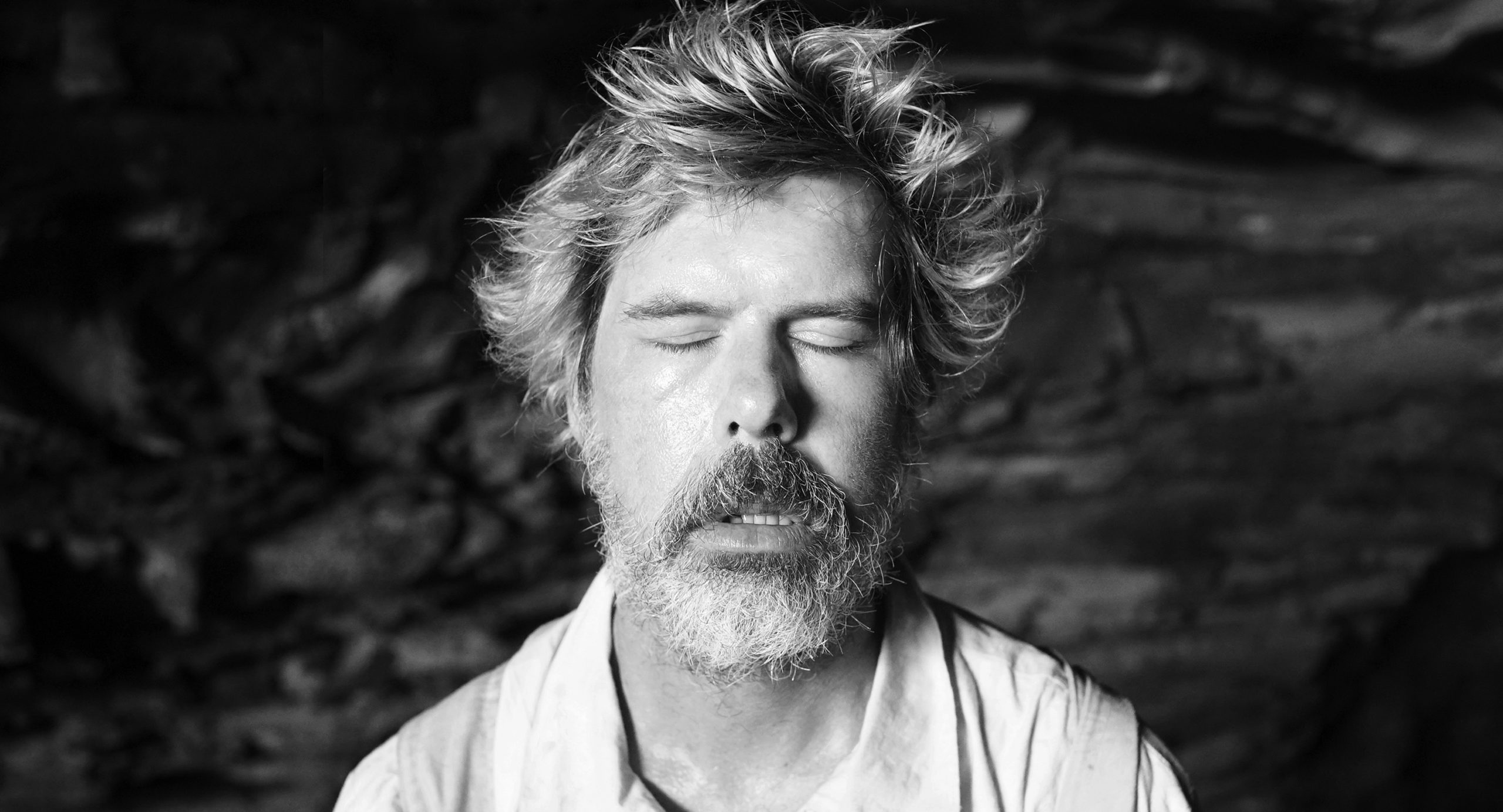

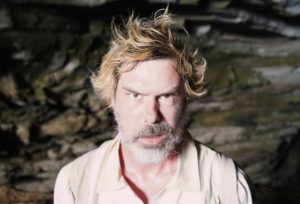

Angus Andrew—the forever centerpiece of Liars—has never been what he’s seemed in the time frame he is seeming it. Though hailing from the expansive suburbs of Melbourne, Australia, Andrew made his musical bones in the scuzzy clutter of the lo-fi Brooklyn post-punk scene of Yeah Yeah Yeahs and The Strokes at the turn of the millennium with the instant-classic They Threw Us All in a Trench and Stuck a Monument on Top. No sooner than Liars rose like cream to the top of the New York skronk-danz pool, Andrew screwed with the format to make scattered, spacious, electro collages on They Were Wrong, So We Drowned. By the time of Liars’ third alarm—like Bowie and Iggy before him—Andrew moved to Berlin for expressionist percussive albums, then for spare, stripped-down rock albums…and so on and so forth.

You get the drill—Andrew refuses to be categorized. Along with leaving the past in the dust as immediately as it happens, he’s a restless and fractured creature, a disrupted, unsolitary being. Having lived many anxious lives within his head and within his physical space, as that anxiety increased, the more it interfered with the everyday. With that, Andrew took to microdosing psilocybin so as to reconnect neural pathways, to connect and examine that which has happened in his past and present, to who he is and where he’s going.

The truth that led to his current focus on mental health has also led him to Liars’ tenth album, The Apple Drop—an expansive, mind-expanding work that seems to tie so much of who Andrew has been, and will be, into a magnetically magnificent package with all of the differently unique voices in his head falling into line.

Let’s duck back 20 years just for the sake of argument—where and what is Liars, today, that it couldn’t have been two decades ago?

With those first works, you have no idea what you’re creating. Specifically, when we made our first record, I had no conception that people would actually listen to it.

Let alone pay attention to it, repeatedly, for years following, with an idea toward who you were.

Right. I was only interested in the idea of making a record, shocked that people would listen. I used the word “pigeonhole” a lot at the time. I felt extraordinarily painted into a corner on that first album. It seemed like people were telling me what Liars was. It became clear to me, from that point forward, to push away from expectations and trod divergent paths. So to answer your question, I would say all that led me to an area of exploration, musically. But having made this new album, I feel as If that exploration—that direction—has been circular.

“I felt extraordinarily painted into a corner on that first album. It seemed like people were telling me what Liars was. It became clear to me, from that point forward, to push away from expectations and trod divergent paths.”

Who are you now—psychologically, spiritually—that you weren’t 20 years ago?

I feel like, as a creator, when you begin your path, it’s a searching experience. I believe that I’m in the same position. I’ve always attempted to keep the process educational. With each record, I want to find a way of working that I haven’t done before—that feels fresh and brand new. I’ve been able to keep doing that somehow.

What, then, is the unique way in which you worked for The Apple Drop? I know you brought in some avant-garde players to back you.

I did. Very schooled musicians who were able to realize every musical fantasy I was dreaming up. It was understood from the start that this was a project where I wanted to lean on the musicians to help me develop ideas. To be honest with you, this wasn’t something that I did in the past. Normally I create most of the songs’ inner workings before bringing them to the unit. This was the first time I could freestyle with these sort of skilled musicians alongside me. As much as this has a live-band feel, the computer is still a powerful tool. There was a lot of journeying to get to the final result.

Is it fair to say that a lot of this was about letting go in a way you hadn’t considered in the past?

Definitely. In fact, in a very general way, my connection to other creators, other people, expanded in the last several years since I came back to Australia. For the first time, I began to allocate time to listening to other people. That had a real effect on me. I had forever avoided any sort of musical community.

“The idea of escaping that initial musical community is a big part of who I am, and it’s taken me this long to begin to consider all that again.”

Does this avoidance have anything to do with the fact that Liars got lumped into the whole NYC scene of the 2000s?

At the time I resented it a lot. I moved from NYC to New Jersey for the next record—which is probably uncool—and attempted to sink the ship that we had floated. That set a precedent for the way I looked at records—to step further away from where you had been before. The idea of escaping that initial musical community is a big part of who I am, and it’s taken me this long to begin to consider all that again.

You don’t want to be part of any group that would have you as its member?

With hindsight I have a lot of gratitude that we were swept up in that wave. I’m not sure I would be speaking with you today if those stars didn’t align as they did.

North of Sydney, isolated as you are, I’m guessing having to deal with the pandemic changed little for you.

That’s right. The pandemic’s effect on my life is minimal. Still, it takes a psychological toll.

Did that work against you on The Apple Drop?

Certainly the global slowdown did. Other than having America burn as it did, there was quiet here. There was time for reassessment. A lot of the ideas for these songs had developed over several years and I had gotten to a point where I needed to ask for musical help. Some of these ideas had grown to a size larger than I was. Once I realized the potential of other voices, I kicked myself as to why I had never done this before. Why not, for example, have a female perspective on a world where a new sonic universe was being created? Suddenly that became a great tool.

“The psilocybin creates a more synesthetic effect, where you feel, physically, a deeper connection to the music rather than just the conceptual or the intellectual… I can recall having a physical reaction to how that sound was working.”

There’s something else at work here. I don’t want to call it science fiction…

When I began working on Apple Drop, I was seeing it as an internal psychological journey. My mind. The mind. As I worked with another writer, as well as the album’s art director, it expanded, lent itself to sci-fi trope. I didn’t set out to do that. It’s still best represented by my inner journey, but when you want to expand on that, the sci-fi trope really helps.

Recently you began microdosing psilocybin as part of a healing process, to get around anxiety. Are there moments on this record where you can best sense how such self-medication has opened the material?

I was put on SSRIs right after the first record, and was taking them the whole time—attempting several times to get off them. A difficult process, physically and mentally. I learned that microdosing could help with that transition, getting off such medications and onto something more natural. I followed that regimen, and did successfully wean myself from those meds. The psilocybin creates a more synesthetic effect, where you feel, physically, a deeper connection to the music rather than just the conceptual or the intellectual. There’s a moment, for instance, in “King of the Crooks” where you can hear its instruments taking the lead, and I can recall having a physical reaction to how that sound was working. Deeply feeling it. That’s a moment where the synaptic gaps and the drug opens. I don’t think that moment would have been here otherwise. FL