You know The Velvet Underground: the pre-Stonewall, drug-infused poetic lyrics of rock-and-roller Lou Reed and the musty avant-classicism of John Cale. How Cale’s experiments in drone repetition, Maureen Tucker’s economic drumming, Sterling Morrison’s Gamelan guitar lines, and Reed’s dreary, lit-witty romanticism inspired a brand-name mentor (Pop king Andy Warhol) and his minion (including Fellini-actress-turned-one-note-chanteuse Nico) to “produce” the most auspicious and influential (I’ll stand by that dogma) debut album of all time. Along with the timeworn Brian Eno trope that follows my throwdown theory, there’s the fact of Warhol’s Factory, of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, of a more outré and scarier second album White Light/White Heat without Andy and Nico, to say nothing of Reed’s cattiness and provoked in-fighting that pushed Cale out of a band he helped create.

All this, and more, is at the heart of acclaimed filmmaker Todd Haynes’ documentary The Velvet Underground—a film billed as an immersive experience into not only the quintessential New York City quartet’s image and music (the two-CD soundtrack is a must, featuring, as it does, a great latter-day Velvets live iteration of “After Hours”), but how such vision (the Velvets’ and Warhol’s) fit into Manhattan’s then-current avant-garde film scene. That sensory overload is prevalent throughout Haynes’ new film with a vibe that Cale describes as a mix of “the elegant and the brutal.” Along with interviewing and dedicating the documentary to the legendary cinema curator Jonas Mekas before his passing, The Velvet Underground features bits of Warhol’s experimental films Empire and Sleep, as well as his screen test series, along with clips of color-saturated, avant-garde classics such as Scorpio Rising and Flaming Creatures so as to pen a visual love letter to the 1960s film world. Unlike most music documentaries, The Velvet Underground is more scene than show, with less concert footage than there is stops into the cinematic and art gallery experience.

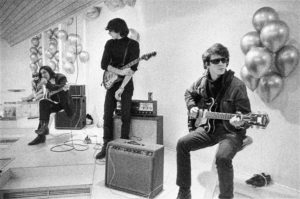

“Part of that is, yes, because there was like no concert footage,” says Haynes with a laugh, before noting his use of footage filmed in Chicago in 1966. “It doesn’t exist—there’s no promotional material from the record label, no shots of them on tour. They really only exist in the cinema of Andy Warhol. The band also happened to be friends, colleagues, and collaborators with so many of the other experimental New York City filmmakers of the time like Jack Smith, with whom Cale and Tony Conrad worked in their Ludlow Street apartment. Mekas’ Film-Makers’ cinematheque became a scene, too, beyond just a place to show films, and its house band was The Velvet Underground. The band just happened to come into form in tandem with that scene, and came up through that experimental culture and art-making.”

The best manner in which to show all of that influence and interactivity between art forms and experimental genres—“No better way to show off the time, the place, and the visuals”—than to use the haunting language of avant-garde film at its height within Haynes’ new documentary.

Longtime Velvet Underground fans and adventurous discoverers of outré cinema and music will get a first-row seat to several scenes of the mid-to-late 1960s—not only those relating directly to the Velvets’ vividly realistic and poetic view of drugs and sexuality and its churning combine of drone proto-punk musicality, but also into the relationships that made the Velvets majestic and helped turn their stark stage show into something as visually propulsive as it was maniacal and sonically dynamic. Subjects such as dancer-actor Mary Woronov (who appears now as an interview subject of Haynes), Mo Tucker, and, of course, Nico (handsome up through the film’s finale at the Bataclan with Reed and Cale in 1972), are portrayed as the heroines of the all-male Warhol-Reed-Cale tale, highlighting that women, too, were a beyond-crucial artistic aspect of the Factory/Velvet story.

“The combination of Mo Tucker and Nico being part of the same first record as Reed and Cale, or having someone as fierce, independent, and brilliant as Mary Woronov dancing on-stage with Warhol assistant Gerard Malanga—it really blows my mind.”

“Thanks for recognizing that,” Haynes says. “During her interview in the film, Amy Taubin puts that all somewhat into context by saying that as a young woman at The Factory she felt the competition of the focus being on how you looked. I completely appreciated her observation. She mentioned how as a woman of The Factory, she did not enjoy the status of a Nico or of an Edie Sedgwick because it all came down to looks. Not many of the men—the young guys appearing in Warhol’s films, or hanging around—faced such physical scrutiny, either. In that way they could feel as sexual as the women because of the gay culture at The Factory. The roles that women played were unique—especially Mo Tucker, who came fully formed as an artist and was truly one of rock’s most notable drummers with her own sound and her own sensibilities. The combination of Mo and Nico being part of the same first record as Reed and Cale, or having someone as fierce, independent, and brilliant as Mary Woronov dancing on-stage with Warhol assistant Gerard Malanga—it really blows my mind.”

Along with that male dominance—one that allows the still-living Cale to finally get his due as Reed’s complete and total partner and equal in VU’s creation of a sound, a vision, and all of its nuances—Haynes’ The Velvet Underground focuses its energy on how Reed and Cale, separately then equally, made the quartet (also with second guitarist Morrison and drummer Tucker) into a singular voice for violence, sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Having previously displayed his love for abstract music and skill for twisting iconic imagery in films such as Velvet Goldmine and I’m Not There (which fictionalized the relationship between David Bowie and Iggy Pop and the life of Bob Dylan, respectively), Haynes is a master at marrying towering scenes to the saints that haunt them. The Velvet Underground documentary just happens to be the time, place, and people that made everything else happen, and Haynes treats that with reverence, shock, and awe. FL