Welcome to Rearview Mirror, a monthly movie column in which I re-view and then re-review a movie I have already seen under the new (and improved?) critical lens of 2021. I’m so happy you’re here.

I remember vividly when Marie Antoinette hit theaters 15 years ago. A young teen still developing her adult taste, I glommed onto it the way my peers had with the works of Tim Burton or Amélie. I made it part of my personality, plastering my bedroom walls with pages I ripped out from the lush spread the stars got in Vogue, playing the deluxe double-disc soundtrack on repeat, adding the DVD to my small collection. After seeing the movie only once, I declared it probably my favorite, even though I had also found it just a little boring. In the years to come, I’d dress as the titular queen for Halloween, eagerly parrot my aunt’s assessment that the movie was “really more of a tone poem,” and assign myself The Virgin Suicides and Lost in Translation as Sofia Coppola homework. I thought the modern music was the coolest thing in the world.

Actually, the second coolest; the purple Converse were the coolest. Actually, no, the coolest thing in the world—and by the world, I mean Tumblr—were the behind-the-scenes photos of Dunst and Schwartzman using laptops in costume. Because Marie Antoinette was both more and less than a movie. It was a vibe. Revisiting it this week, I am more certain than ever that the critics who relegated it to a Rotten Tomatoes score of 57 percent mostly missed the point. They wanted it to be impactful or stirring or erudite like the adventures unfolding at the Bastille or the great thinkers of Paris. But the movie is Versailles.

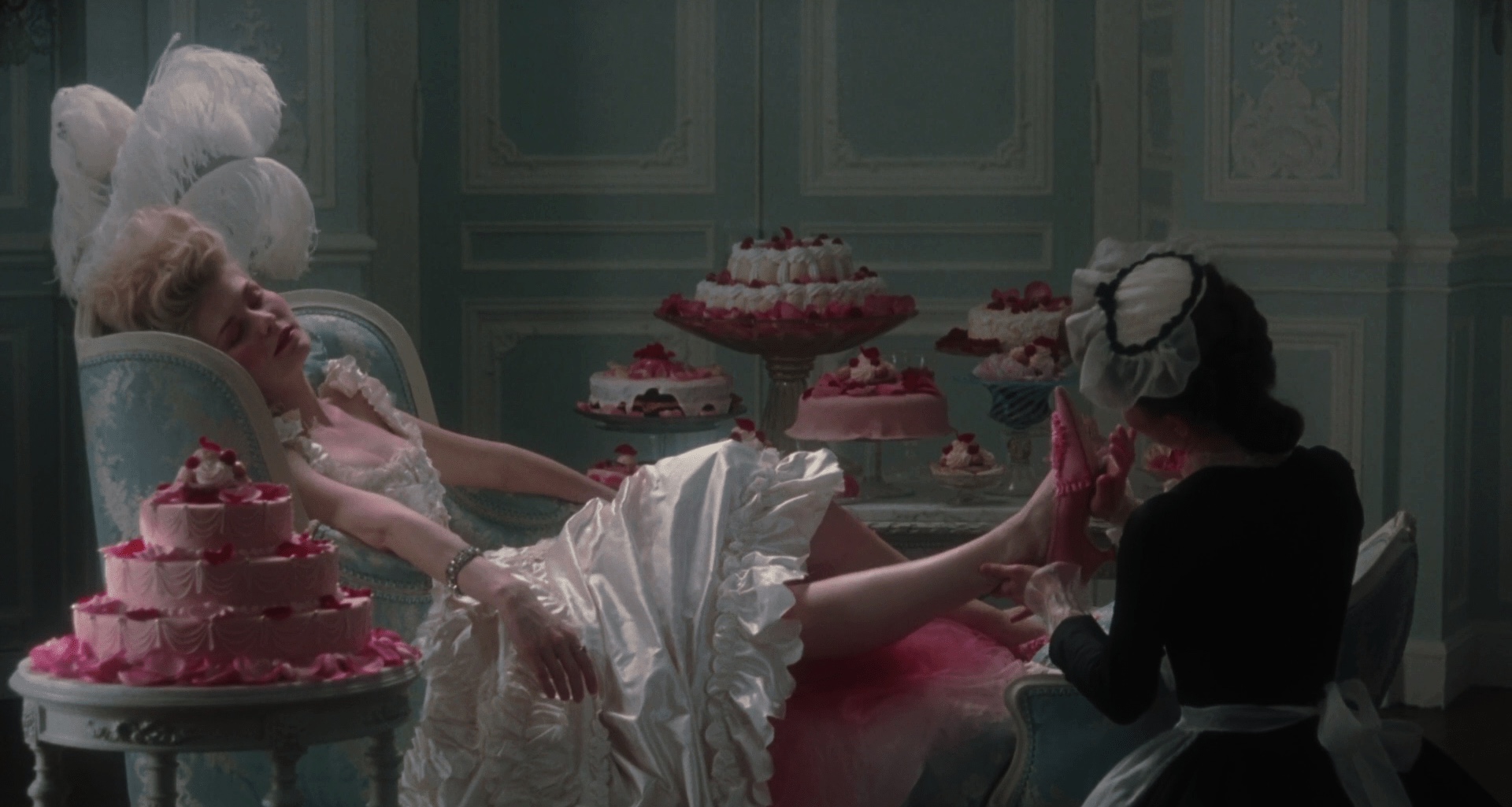

It’s not exactly a coming-of-age tale, but it does follow a young woman’s maturation from sweet, innocent, and naive to self-absorbed, sensual, and loving. Dunst is charming in the lead role, though she’s almost crowded out of the movie by a stellar cast, including Rose Byrne as a bon vivant, Jamie Dornan as a boy toy, Rip Torn as the King of France, Asia Argento as his mistress, Judy Davis as Marie’s minder, Steve Coogan as her ally, Danny Huston as her brother, and Jason Schwartzman giving a powerfully subtle comedic performance as Marie’s unsophisticated husband. Shot on the actual grounds of the palace and filled to the brim with colorful costumes and scenery, it’s a feast for the eyes that doesn’t apologize for its decadence, making the world of court look so tempting that it’s easy to see how a sheltered princess might forget about the starving peasants outside. The queen is depicted here as neither Diana-like victim, nor Catherine the Great–esque hero, nor Evita-ish villain. Instead she’s an artist, and her life is her canvas. She lived too much and too grandly, but oh, she did it well.

It’s not even really an attempt to render history. It’s a celebration of imagination with the necessary caveat that, yeah, heads of state really shouldn’t let their class just spend, or live, wildly. It’s about being young and in love with your life in a gilded cage. And also femininity, probably, I guess.

Yes, it’s a bit slow in parts. I think this is intentional. Even a life of partying can get dull, and we’re drawn into Marie’s boredom so that we might understand why she felt she needed to escape to the Petit Trianon. Her faults and her heartbreaks are presented in equal measure, and never lingered on. We see servants cleaning up her mess after a party and, later, cleaning the eggs on her playhouse of a farm. When she loses a child, it’s communicated simply through an absence in a painting, and the funeral is wordless and unsentimental. The movie is more gleeful in depicting parties, cakes, fashion, and all other manner of excess, which is part of why it’s aged so well, I think. There’s no whiff of a girlboss narrative, no particular judgment about the sexual mores—or lack thereof—among Marie and the company she keeps. There’s little by way of overt messaging and certainly no moral. It’s not even really an attempt to render history. It’s a celebration of imagination with the necessary caveat that, yeah, heads of state really shouldn’t let their class just spend, or live, wildly. It’s about being young and in love with your life in a gilded cage. And also femininity, probably, I guess.

And yet, in this age of billionaires going to space as the world suffers through a pandemic, I kept searching for some kind of connection, how it either did or didn’t predict our current era of extreme wealth inequality. Would I see shades of Ivanka Trump in the heroine, cloistered with her children away from the rioting masses? Not really. The movie avoids parable. Maybe today’s rich kids are as vapidly happy as Marie and the nobility were, content to believe that God himself has anointed them rich as fuck, but, well, that’s not the impression I get from Succession. At their peak, Kimye tried it—the opulence, the tacky displays, the unabashed luxury. But they were always trying so hard, always hustling, always striving. In this tale, Marie’s place atop the pyramid is simply a fact, unquestionable until, literally, the revolution.

And anyway, the movie isn’t really about wealth; when you own the country, what is money? If everything is decadent, nothing is. In the world of Marie Antoinette, bread and cake are interchangeable, because every meal can be dessert. And that’s what the movie is, too: dessert. Rich, creamy, sumptuous, delicious. Not particularly healthy, but so distracting. And distraction seems to be what Marie craved above all. FL