A few months ago, I was interviewing Face to Face’s frontman Trever Keith about the band’s latest album No Way Out But Through and we started talking about a skit they had on their 1995 LP Big Choice. In the skit, the band are arguing with their (real life) producer and label owner about their song “Disconnected” being included on the album. When we spoke about this decision over 25 years later, Keith explained that it was a way to beat their fans to the punch of calling them “sellouts” for their move to a subsidiary of a major label, and also have a little bit of fun at their own expense. Face to Face ended the skit by explaining, “There’s no way in hell that song is going on the record,” a beat before the opening chords of the re-recorded rendition of the song abruptly cuts off the conversation.

A few months ago, I was interviewing Face to Face’s frontman Trever Keith about the band’s latest album No Way Out But Through and we started talking about a skit they had on their 1995 LP Big Choice. In the skit, the band are arguing with their (real life) producer and label owner about their song “Disconnected” being included on the album. When we spoke about this decision over 25 years later, Keith explained that it was a way to beat their fans to the punch of calling them “sellouts” for their move to a subsidiary of a major label, and also have a little bit of fun at their own expense. Face to Face ended the skit by explaining, “There’s no way in hell that song is going on the record,” a beat before the opening chords of the re-recorded rendition of the song abruptly cuts off the conversation.

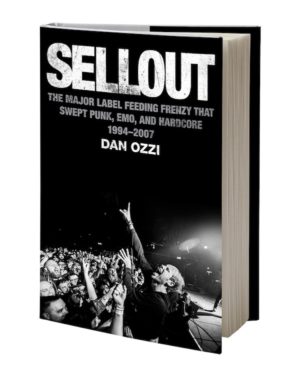

This phenomenon of selling out is analyzed in detail in Dan Ozzi’s aptly titled book Sellout: The Major-Label Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore (1994-2007). The story is centered around 11 major-label debut albums and is told from the perspective of the band members, label executives, and peers who lived through the experiences. Admittedly in a time when self-promotion via social media is ubiquitous and indie bands aspire to get their music placed in Apple commercials, the idea of “selling out” seems so benign it’s almost quaint. However, that certainly wasn’t the case when the bands featured in Sellout came of age.

Anyone familiar with Ozzi’s writing knows that he’s very good at making fun of things, however he manages to tell these stories without sarcasm or snark, fully conveying how destructive this phenomenon was for Bay Area bands like Green Day and Jawbreaker whose decision to move to a major-label completely alienated their fan bases and led to violence, meltdowns, and break-ups along the way. But what’s most interesting is the way Ozzi characterizes the unique nuances between these bands and their audiences and why the aforementioned acts bore the brunt of this self-righteous indignation more than, say, Jimmy Eat World or The Donnas.

While punk and hardcore fans will be familiar with the general circumstances around many of these bands’ mythologies—such as Victory Records famously making Thursday whoopie cushions, or At the Drive-In’s explosive energy forcing them to prematurely implode—Ozzi is able to provide context and details to these situations in a way that makes the stories as compelling to completists as they are to casual fans. This is due to the fact that he’s able to craft a cohesive narrative that weaves through the book, connecting these stories and musicians through a staggering amount of interviews and research. It’s a tricky task, however the dots are connected in a way that illustrates the real-life crossover of these seemingly disparate acts and keeps the book rooted in reality.

Above all, Sellout is a compelling time capsule of a time before social media dominated our lives, and bands could make a living without resorting to meet-and-greets, VIP experiences, and other supplementary income streams that would make Maximum Rocknroll columnists scoff. By exploring this phenomenon instead of critiquing it, Ozzi has crafted a book that’s about selling out, but is also about so much more: It’s a document of an era and ideology that lives on today in creased liner notes, pixelated YouTube videos, and the kinetic energy of upstart acts who were inspired by the bands chronicled here.