After the ultimately unsatisfactory gloss and floss of his post–Let’s Dance ’80s, David Bowie’s ’90s were set to be a dramatic rearrangement of his goals with an intent to experiment. Starting with his raw-knuckled kind-of-band Tin Machine’s albums, Bowie’s aim was to shake out the doldrums that put him squarely in rock’s mainstream with a volition to herald art above commerce. That meant Bowie remaking his initial version of plastic soul (that which he called 1975’s Young Americans) into something jazzy and spacious with Black Tie White Noise, the ambient whirr of The Buddha of Suburbia’s soundtrack, returning to the Eno-driven avant-garde scene of Low and Heroes with the wonky Outside and its electro-jungle-inspired sister Earthling, before ending the decade with the slickly strange and dramatic AOR of Hours and starting the 21st century with a look back to his youthful self with Toy, an album famously unreleased.

Until now, that is, with the penultimate of chronological Bowie box sets from Parlophone/Rhino, Brilliant Adventure (1992–2001), which precedes the last decade before his passing in 2016. While most of the albums that fill Brilliant Adventure feature old friends and longtime collaborators such as pianist Mike Garson, guitarist Carlos Alomar, and producers Tony Visconti and Nile Rodgers, the Bowie ’90s were steeped with new musicians to his fold in bassist Gail Ann Dorsey, drummer Zack Alford, guitarist Reeves Gabrels, and multi-instrumentalist Mark Plati. “It’s interesting having these things come to light at this point,” says Plati, not only of the never-before released Toy project of re-recorded, pre–Space Oddity songs initially rejected by his then-label Virgin, but of an upcoming new Bowie documentary directed by Brett Morgen filled with never-viewed live performances. “I’m excited by it all, especially seeing Toy have its day with a proper release. Now that David’s no longer with us, sadly, there’s an additional weight that we attach to it.”

“With Bowie, we were moving so quickly. You hardly ever knew what was coming out when. We were too busy actually doing them. Seeing the Brilliant Adventure vinyl now, and realizing how heavy it is…so much of my life is in that box.”

Surely Plati is talking about Brilliant Adventure box set tracks such as “Real Cool World” (from the soundtrack to Ralph Bakshi’s bizarre 1992 noir-cartoon Cool World), a slow Bowie duet with Dorsey “Planet of Dreams,” a cover for the HIV-AIDs charity Red Hot, “A Foggy Day in London Town” with Angelo Badalamenti, and songs from the video game Omikron: The Nomad Soul. In particular, Plati had all but forgotten about the box’s BBC live radio theater showcase (“I never finished mixing five of its tunes from the desk”). Other songs in the collection that move Plati greatly are Bowie’s hot-wired version of Bob Dylan’s “Trying to Get to Heaven” and the intense take on Bowie’s own “Karma Man” from the Toy sessions in 2000.

“I hadn’t heard the BBC sessions since I played on it, and had forgotten about so many of the songs here—one-offs the likes of which we worked on all the time,” says Plati of songs either filed away or missing in action. “Like the Toy stuff. I never had a copy of the tapes. Lucky for me that I wrote it all down because there were so many little recording bits that I actually almost forgot. Back then, with Bowie, we were moving so quickly. You hardly ever knew what was coming out when. We were too busy actually doing them. Seeing the Brilliant Adventure vinyl now, and realizing how heavy it is…so much of my life is in that box. It reminded me of what it felt like, then, to lug around two-inch tapes and handle tangible work. It takes real effort to move it around.”

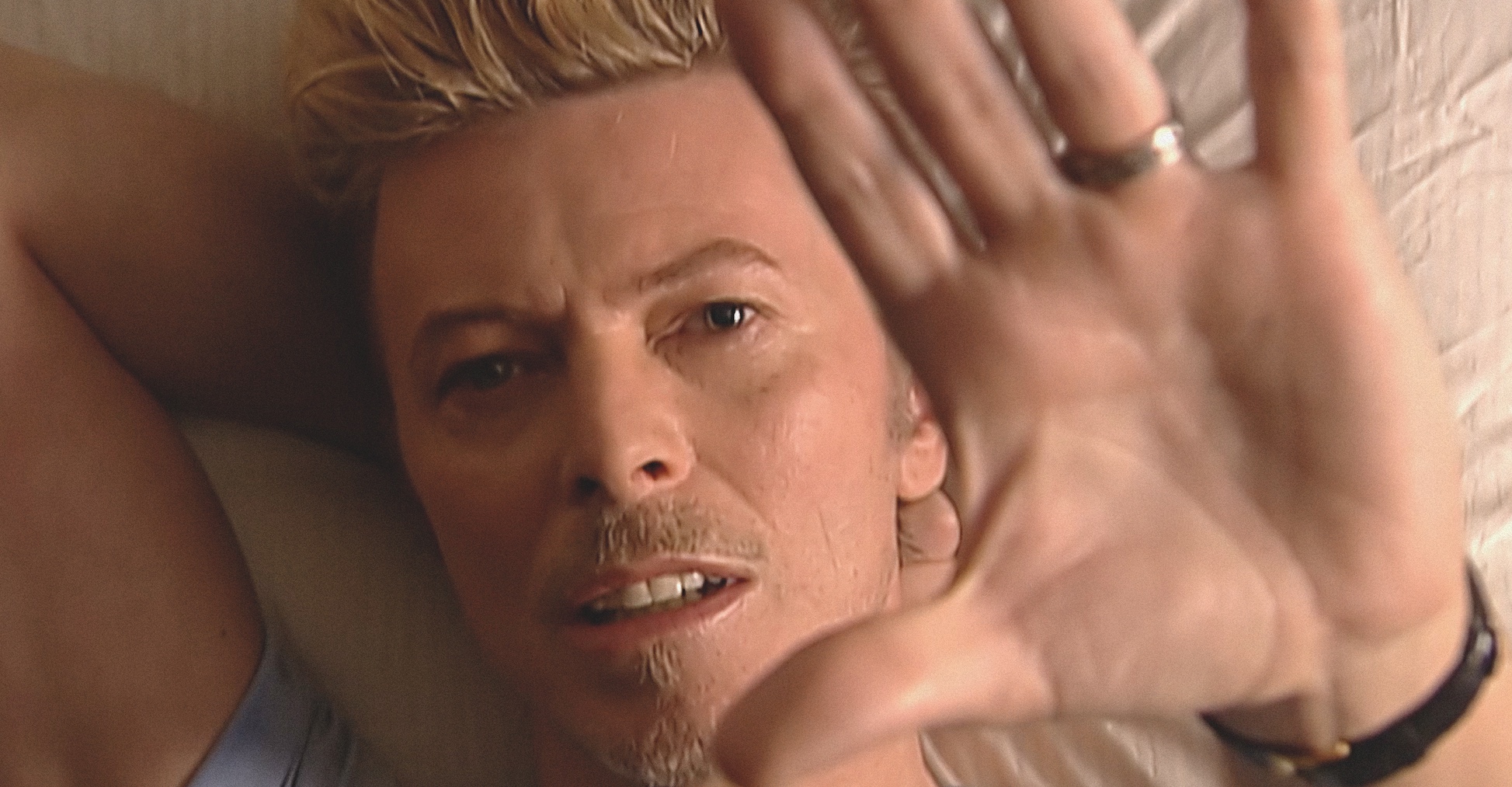

photo by Nina Schultz

Plati goes backward to discuss becoming quick friends with Bowie once introduced by Reeves Gabrels after having been a mixologist-engineer at Philip Glass’ Looking Glass Studios for a number of years. “It was a happy accident,” starts Plati. “Bowie was moving from the Hit Factory where he had been working a lot at that point in the early-’90s to a new space. And the great thing about Phil’s studio was that it had a window. Such a small thing, but you didn’t feel so clouded over there, as no other studios had windows. For us studio rats, that meant daylight.” Bowie had already had a connection to Glass as the latter had created a series of minimalist symphonies based on the former’s Low, Heroes, and Lodger albums. So when they met at Glass’ NYC studio while working on a new Bowie track, “Telling Lies,” Plati found himself quickly involved with the proceedings.

“I was going to just be the song’s engineer and synth programming guy—that’s pretty much it—but Bowie, Reeves, and I just got on like a house on fire,” states Plati. “We vibed. Our sense of humor was in sync. We just got along from the get-go, and at the end of the week David told me that he would come back to work with me after his summer festival tour that year. Yeah sure, right? Everyone promises everything, so it’s hard to get excited until it happened. But he was a man of his word, and sure enough, we started a new record that became Earthling.”

“No sooner than I started programming Earthling, my role grew to that of co-producer because of the work that I was contributing. My contributions helped shape the direction of that album, and he was quick to acknowledge it.”

Producing and co-writing with Bowie, as he did on Earthling, must have been a different animal than just playing and sequencing for or behind the legend. To that question, however, Plati gives a ‘yes’ and ‘no’ answer. “There really was so much overlap in those roles, and Bowie was exceedingly generous and quick about it. I mean, no sooner than I started programming Earthling, my role grew to that of co-producer because of the work that I was contributing. My contributions helped shape the direction of that album, and he was quick to acknowledge it. Even the studio atmosphere with him…what he would do is get people with the intent of letting them do what they do. He’d guide you, tell you what he liked and didn’t like. But he wanted you to bring what you brought to the party. So it was all a very organic thing with Bowie, falling into those roles.

“I felt like an oddity as I had many different roles—going from engineer guy to producer to band leader, which was fun—but he just put you up and you did it,” Plati concludes. “He saw things in people that they never saw in themselves, ever. Certainly, that’s what he did with me. When Bowie made me his band leader, that wasn’t something I had ever done before. I told him I wasn’t sure I could do that. He told me that it was just like being a record’s producer, only you were on the bus. And eventually you were just doing everything with him and for him, to the point where, when we got to Hours and Toy, it was completely natural and organic that we were just expected to collaborate with him and contribute. There weren’t many—if any—artists of his stature who would welcome such collaboration, but that’s Bowie.” FL

photo by Nina Schultz